Cultural bridge of colours

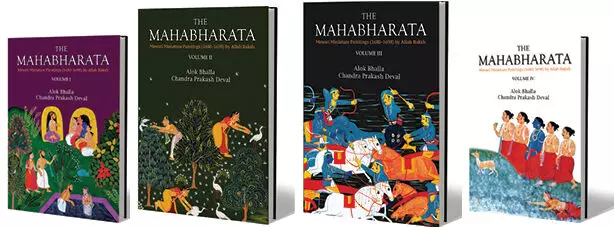

The Mahabharata by Chandra Prakash Deval and Alok Bhalla is a four-volume compilation of Allah Baksh’s miniature paintings— accompanied with faithful Hindi translation of the Mewari text and explanatory English comments— showcasing the artist’s expression of visionary thoughtfulness that would enrich readers’ understanding of the history of cultural exchange between different religions. Excerpts:

‘The dharma of release, where calm prevails,

And the dharma of kings, where force prevails –

How far apart they are!’

—Asvaghosa, Life of the Buddha.

‘Yes,’ said god, ‘you ask me to practice dama, self-control.’

‘Yes,’ answered man, ‘you ask me to practice dana, sharing, giving.’

‘Yes,’ answered asura the primitive, ‘you ask me to practice daya, compassion.’

Prajapati says to them that they had, indeed, understood rightly.

‘Ever since,’ the parable says, ‘the thunder in the sky has repeated that

ultimate instruction: da, da, da. To the gods, given to pleasure: self-control;

to man, given to acquisition: share, give; and to asura the primitive, given

to anger and violence: compassion.’

—Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.

The miniature paintings of the Mahabharata by Allah Baksh, from the late 17th century Mewar, are unique in the history of Indian art because the epic has never been painted in its entirety. Published here for the first time in five volumes, these paintings have been selected from about four thousand extant works illuminating Vyasa’s great poem. We have already printed, in a separate volume, nearly 400 paintings by Allah Baksh offering visionary and visually beautiful interpretations of nearly every shloka of the Gita from the same series. Painted between 1680 and 1698, these miniatures by Allah Baksh were commissioned by Maharana Jai Singh of Mewar (1653–1698). Painted in bright and flat natural colours on paper, each leaf in this illustrated Mahabharata is 41.50 x 25.00 centimetres in size (the paintings of the Gita in this folio are 37.00 x 24.00 centimetres). Every scene is framed, like a sacerdotal space or a mandala, by three bands of colour adding to their beauty and giving them a feeling of calm sublimity. The broadest outer band is in vermilion–red, the colour of creative vitality, blood and hypnotic fire. Agni, the god of fire and of holy speech, plays a crucial role in cycles of destruction and creation in the Mahabharata. Agni always arrives when the epic’s narrative demands that the past and the old, which has become a burden, is burnt away for a radically new spark to rise from the ashes. Indeed, at the very end of the story, as the Pandavas abandon their kingdom and begin their last journey toward heaven, the embodied form of Agni, the god of fire with seven flames, blocks their path and demands that they cast away all their signs and symbols of power which can no longer serve them so that they can know who they are with clarity.

The colour of the innermost frame, which touches the space where human, divine and demonic events in the Mahabharata are depicted, is ochre-yellow. It is not as broad as the vermilion-red. Ochre-yellow is both the colour of the earth on which life in time is lived and of sunlight which illumines everything; it is ethereal and earthly and, is rightly, the colour of Krishna’s garments in the paintings. Separating the vermilionred and the ochre-yellow is always a thin black line, silent and inconspicuous like death. Black, Goethe says, is an ambiguous colour of shadows and disquiet. It signals the deprivation of light, the negation of vision and dark thoughts, obscurity and ethical obtuseness. In his theory of gunas, or the three qualities of the soul in the Gita, Krishna speaks of tamas (darkness) as a condition of dull inertia; as a state of empty moral abyss into which human beings can always fall when they fail to reach out in empathy to all things and all beings to make a meaningful world. The other two gunas are sattva, the state of goodness, purity and harmony, and rajas, the state of outward driving passion, of imagination, which seeks to create something that is radically new. The ‘darkness’ of the framing line is the necessary condition for light and all the other colours of life to exist. Since the Mahabharata is primarily a story of deceit, exile, coercion, sorrow and war, the black line, perhaps, signals how dangerous life can become when we seek power over others, refuse to acknowledge their rights and defile them. Before looking at any illustration of an incident in the epic, the eye, as it moves across from the divine vermilion-red to the earthly ochre-yellow, must travel across this thinnest of black lines.

The three lines, then, can be read as a minimalist parable of the perilous journey the soul, any soul, must make as it struggles with emotions, desires and thoughts that pull it in different directions and produce either divine exaltation, earthly fulfilment or the despair of death (sattva, rajas or tamas). Each and every story in the Mahabharata, the major ones about the gods, rishis and heroes or the incidental ones (akhyanas) about simple folk, animals and birds, describes the success or failure of this journey from crisis through despair to redemption. The black line is the dark night of the soul, the dangerous passage through severe penances or difficult tests required for enlightenment; and, no one is assured of a successful crossing. A god like Indra can be punished for his presumptuousness, a rishi can lose his concentration, a wise man like Bhishma can be caught in a moral labyrinth, a hero like Karna can act with iniquity and a king like Dhritarashtra can fail to act righteously and so live a life of lamentation. For Duryodhana there is nothing higher than his earthly ambition; he remains mired in his ethical darkness.

Only Yudhishthira, perhaps, treads the passage between the earthly and the divine thoughtfully; he questions each decision and every move for its ethical implications for others. Taking nothing for granted, he never assumes that life in time is, as in myths, preordained. It is as if he understands that as he traverses the black line—the tamasic, the violent, the angry or the despondent in every human being—each step is a gamble which his reasoning self must take if it is to find a way through unreason and mendacity; every thinking person must risk (gamble) losing his sovereign self and yet remain calm; must gamble against loaded dice and the mendacity of a Sakuni. Indeed, Yudhishthira never ceases to question and debate, uncertain of the decision he has made or has had to make. Significantly, it is only at the gates of heaven that he finally and firmly makes an unambiguous, non-negotiable and dharmic decision: He will not enter heaven, he tells god, unless the mongrel dog, who may be despised by the ritualists as unclean, but who has walked with him across the difficult mountain path, is also admitted. It is at that moment when he ‘gambles’ with his salvation that all the three gunas (sattva, rajas and tamas) and all the three colours framing these paintings (vermilion-red, ochreyellow and black) recover the old, the original harmony; the presence of each colour becomes the necessary precondition for the existence of all the others.

A broad colophon, ochre-yellow in colour, runs across the length of every painting. It carries information in unselfconscious, colloquial and fluent Mewari prose written in uneven black ink with a kalam (reed pen, perhaps), about the story from the Mahabharata being illustrated. The top left corner of each colophon has information about the particular parva (chapter) followed by the number of the section where the story being illustrated is to be found. At the end of each narrative description there is a numerical figure which may indicate the price of the painting. A few colophons in the Mahabharata and the Gita paintings also declare that the entire work was commissioned (see verse 72 of chapter 2 in the Gita volume) by Maharana Jai Singh of Mewar, and painted between 1680 and 1698. These colophons also inform us that the Mewari text is by Bhat Kishandas (or Bhat Kisandas).

The paintings are housed in three different museums in Rajasthan: the Government Museum in the City Palace, Udaipur; the Udaipur Sangrahalay, Ahar; and, the City Palace Museum, Jaipur. Unfortunately, we have not found a single work illustrating some of the chapters of the epic which must have been part of this very large and extensive oeuvre. It is sad that these self-assured paintings, which never cease to offer hope because the gods are in their sky-boats above and the lakes below are full of lotus flowers, have never been displayed.

We know nothing about Allah Baksh except for an inconspicuous signature, in the lower corner of the illustration for section 52 of the Bhishma Parva, which tells us that the ‘chitrakar’ (painter) is Allah Baksh (or Allah Bakas in Mewari). The signature, however, deepens the shadow of anonymity which surrounds the name Allah Baksh. We are astonished by the humility of the man and by his confidence. It is not, he seems to suggest, the business of an artist to reveal himself; his only duty is to be ‘the priest of beauty’ who finds joy in the concert of colours he has been privileged to see and record. It is possible that he belongs to the family of Nasiruddin (Nasar Deen) of Chawand, who may have migrated from Iran. We can surmise nothing more about his lineage and guess even less.

Perhaps, like most traditional artists of the sacred, a signature is not very important if it leads to no meaningful thoughts about the work. Our knowledge of Allah Baksh’s personal life or religion would make no difference to our response to the paintings because what they are illustrating is not anchored in the artist’s self or drawn from his experience. The references which guide our judgement are either in the Mahabharata text or in the painting itself—the cadence of its lines, the mood of its colours and the specifics of the story. So, the work suggests that we are dealing with a man of strong moral imagination who intuitively understands that the Mahabharata is not a call to war in which everyone kills and dies according to some mythic prophecies whispered by wandering ‘moksha-talkers’; it is, instead, a plea—a hopeless one perhaps—for a more responsible way of becoming a dharma-being.

The lines are confident, the colours are vibrant and the space of every painting, suffused with light, is filled with an endless variety of animals, birds, trees, rivers, mythic creatures, gods and demons. These scenes may, at first, seem to be anomalous in works which are concerned with stories of violence and the slide of time into Kali Yuga (the age of darkness), but their insistent presence in nearly all the paintings suggests that for the artist visions of beauty ought to form the normal environment in which life should flourish. These images are not created because they are part of the convention of Mewari art as decorative additions, but should be read as aids to reflections on the dharma of ahimsa whose erosion Vyasa bemoans throughout the Mahabharata. They encourage a two-fold response: one to the age of beauty and truth and the other to its erosion. That is why one is morally shocked when one comes across images and stories in which the gods conspire with heroes to burn forests down or wrathful men slaughter so many that lakes are filled with blood. Allah Baksh believes, like Vyasa, that there is no honour in such destruction; that suffering is not a condition of life but is always caused by people who do not understand that selfish power is ‘as insubstantial as burning flames fed by straw or the bubbles of froth seen on the surface of water.’ For a painter of the Mahabharata this is a unique perspective and his paintings deserve an honoured place in the history of Indian miniature art.

(Excerpted with permission from Chandra Prakash Deval & Alok Bhalla’s The Mahabharata; published by Niyogi Books)