A tale of love amidst strife

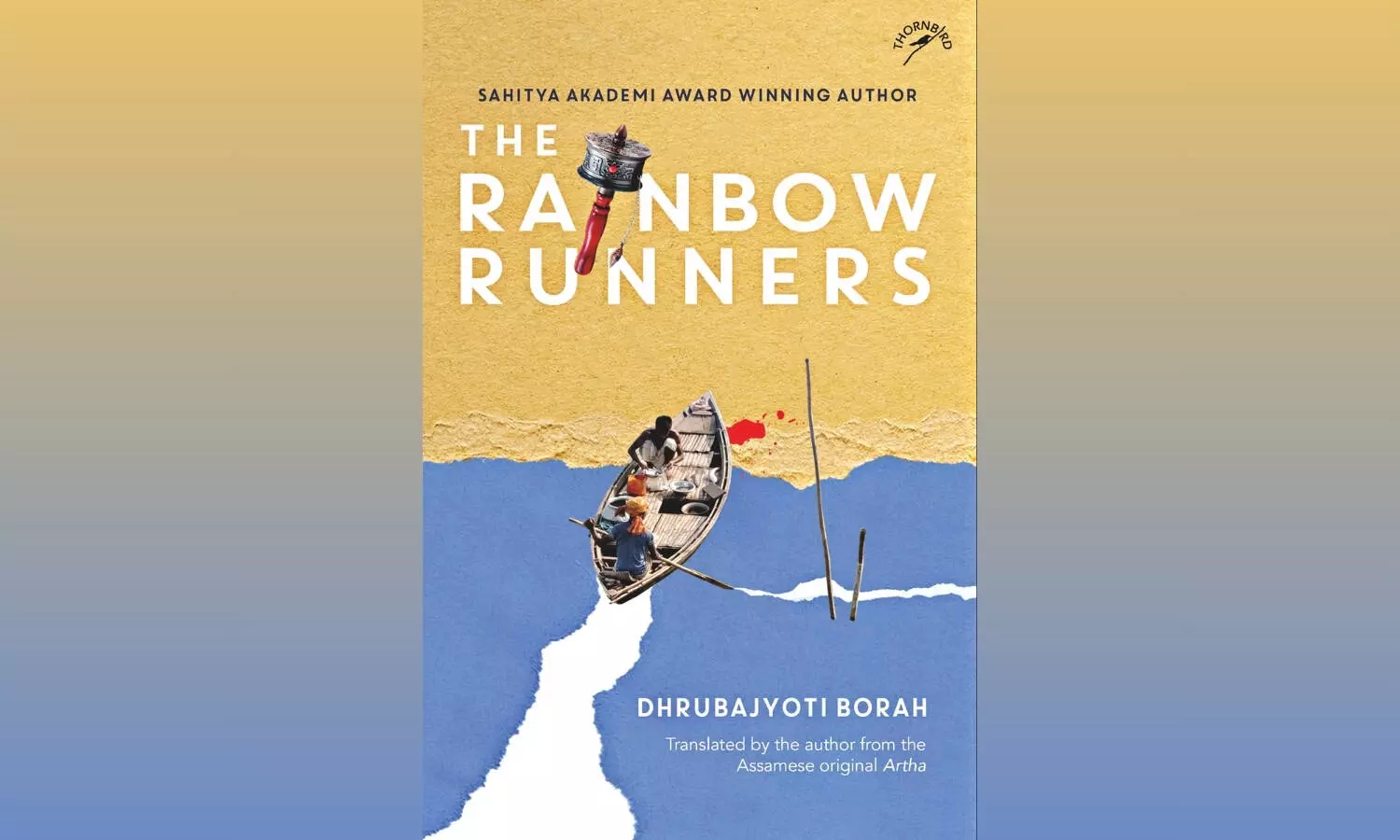

‘The Rainbow Runners’—translated by Dhrubajyoti Borah from the Assamese original Artha—is a poignant love story that deploys experimental narration to capture the turmoil of insurgency-hit Assam through the perspective of a young man.

The sky had lightened up. There would be sunshine today. With the sun up those who had gone out trekking would be able to see the beautiful vistas. Sometimes the Dhauladhar range remained buried under mists and clouds.

I suddenly said, ‘Come let’s go down to the village. We can have our lunch there. One of our porters’ mother does the cooking. She can come and cook our meals here as well. Otherwise it’s not very easy to cook on this huge stove.’

Her eyes shone brightly as she asked, ‘Shall we get local food?’

‘Local food means rice, dal, boiled potatoes and fried green vegetable. They might be able to provide boiled eggs at the most. If you want meat you have to inform them in advance.’

‘That’s exactly the kind of food I have been craving.’

She stood up, rubbed her hands and quickly got ready to go out. I felt happy at this transformation in the sad girl.

She came out of her room, stood near the door and asked, ‘Do we have to lock it?’

‘Yes, better to put a lock on it.’

We came out after locking the door. Closing the small wooden gate of the base camp we walked over the dilapidated metalled road and went towards the village. Though the village can be clearly seen from the base camp, by the serpentine hill road it really is more than half a kilometre away. In a narrow valley-like gorge of the mountain there were about thirty small houses of different types on both sides of the road that passed through it. Two or three houses were double-storeyed, the rest were single-storey houses. The houses were built with different-sized stones hewn from the mountains cemented by mud or limestone paste. Each house had a narrow veranda in front. There were two or three tiny shops there. Vegetables, grocery items, other provisions, bread and biscuits and a few toiletry items were sold there. The shops mainly operated during the trekking season. At other times only the grocery provision shop remained. That was the only permanent shop of the village.

‘Why have they built the houses one on top of the other? In such a narrow strip? The houses are nearly on the street. A vehicle will pass through only with great difficulty.’

‘I had also asked the same question.’

‘What answer did you get?’

‘Because of the natural conditions. Very strong winds blow down from the Dhauladhar mountains. Very cold and strong winds. This place is safe and protected from these gale-like winds. You don’t have an idea how fierce and cold these mountain winds can be.’

‘Do you?’

‘I have experienced it on one occasion.’

‘Blizzard?’

‘It wasn’t a blizzard really. Blizzards occur above the snowline—where there is snow throughout the year. In the Dhauladhar range only the higher peaks are covered in snow during summer. In the Pir Panjal range to the north or in the Ladakh Himalayas snow remains throughout the year. There are huge white fields of ice and snow there. I have, however, not seen them.’

‘I have seen such places.’

‘Where?’

‘In America.’

‘Yes, there is heavy snowfall there, isn’t there?’

‘What happened when you got caught in the blizzard?’

‘I might have got a lash from the tail of a blizzard. It was a nightmare.’

We ate rice, dal, cooked greens, boiled potatoes and eggs served by the porter’s mother. I observed that she had asked for a little mustard oil and salt and with them mashed the potatoes and the egg together. I looked at her surprised.

‘What are you looking at?’ she asked.

‘Such an egg-potato mash is a favourite among my people.’

She had smiled, but didn’t say anything.

I engaged the porter’s mother who was also the wife of our chowkidar to cook for us during these six days. My job in the village was to draw up the final calculation of the porters’ dues and to pay them the money. I was also going to engage them in advance for the upcoming trekking season after the rains. For that a little advance money has to be paid, around two hundred rupees per head. It’s not easy to get good porters and guides always, specially ones you can rely on. One cannot send the foreigners who come trekking in the mountain wilderness with just anyone for so many days. I told her these things. What else was there to talk about anyway?

‘How long have you been in this line?’

‘It’s been two years now.’

‘You are very lucky to have lived here for two entire years.’ Then after a pause she asked, ‘But how did you come from faraway Assam to Himachal Pradesh and Kashmir?’

I was startled. ‘Assam?’

‘Your surname is a typically Assamese title.’

‘How do you know that?’

‘You introduced yourself when you had welcomed us at the beginning.’

‘You are also Indian. Which state do you belong to?’

‘I am an American citizen.’

‘Nevertheless, you are of Indian origin.’

She nodded. A mischievous smile spread over her face. Her eyes sparkled behind her glasses. ‘I am also Assamese.’

‘I had my suspicions when you ate mashed eggs and potatoes with raw mustard oil and salt. Wherefrom in Assam?’

‘I will tell you all that later. But you have not yet answered my question.’

‘What question?’

‘How and why did you come here?’

‘I came here via rail and bus in search of a job.’

‘Is that the real answer?’

‘Do you doubt it?’

‘No, I don’t doubt it, but maybe that’s not the entire answer.’

‘What makes you think that?’

‘Because Assamese boys don’t come this far for jobs.’

‘They do come nowadays.’

‘Why do they come nowadays?’

‘What will they do in Assam?’

‘Are there no jobs in Assam?’

‘There may be work, but no fitting atmosphere. All that happens are shootings, beatings, military operations, underground—over ground. It’s possible that all the news does not travel to faraway America.’

‘We do know, at least some of it. Really Assam has changed drastically has it not?’

‘Beyond recognition. Totally beyond recognition.’

‘Have the people also changed?’

‘In reality the age of simplicity and innocence is over in Assam. You can say—the end of innocence…’

(Excerpted with permission from Dhrubajyoti Borah’s ‘The Rainbow Runners’; published by Niyogi Books )