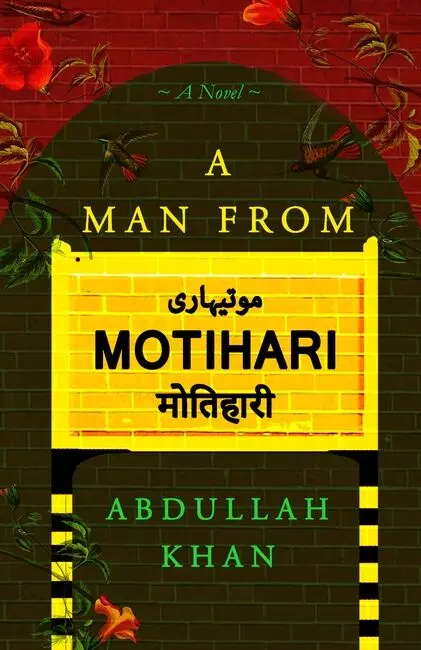

A poignant tale from the ‘heartland’

Set against the backdrop of the rising tide of Hindutva, Abdullah Khan’s novel, ‘A Man from Motihari’, tells the story of an aspiring writer from the hinterlands of Bihar, who grapples with the questions of identity, caste, religion and other things woven into the complex fabric of contemporary society

Abdullah Khan’s second novel, ‘A Man from Motihari’, tells the life of Aslam Khan, a middle-class Muslim boy from Bihar, amid India’s changing social and political landscape. Aslam, born in a haunted bungalow in Bihar, shares his birthday and room with George Orwell, the British writer born seven decades earlier. This forms the backdrop for Aslam’s poignant journey through love, struggles, and self-discovery.

The novel starts with Aslam saying, “I was born in a haunted bungalow. And the midwife was a ghost.” Aslam, influenced by the timing of his birth and Orwell’s writings, dreams of becoming a writer. However, over time he discovers that being a writer, especially for a middle-class person in India, is extremely challenging, and making a living from writing seems nearly impossible.

Aslam’s character is crafted with care, a dapper and well-educated individual grappling with personal demons, traumas, and aspirations. The novel provides a window into the socio-political fabric of India, exploring the impact of right-wing Hindu politics on Aslam’s life and relationships. The exploration of Muslim communities, the caste system, and their influence on status and relationships adds depth to the story.

Abdullah Khan writes in the novel:

‘At the end of October 1992, I went to Arvind’s house to return The Discovery of India, which I had borrowed from him. As I entered Arvind’s bedroom unannounced, I found that Shambhu was already there and seemed to be in the middle of a serious discussion with Arvind. A bunch of booklets lay on the bed next to them and out of curiosity, I picked one up.

The president of the Indian Nationalist Party, Lalwani, with his trademark toothbrush moustache and sinister smile, was on the cover. In the background was the proposed temple along with a blurry picture of the four-hundred-year-old mosque. On the top left of the cover was the party symbol of the trident and on the top right the slogan: ‘Kasam Ram ki khate hain / Mandir wahin banayenge (We vow in the name of Lord Rama that we will construct the temple at the same place)’.

The local newspaper had published Lalwani’s plans to agitate for the construction of the temple in Ayodhya on the front page. A close-up of Lalwani in a pensive mood had accompanied the article. After reading the news item, Abba had commented, ‘This neta will get thousands of Indians killed to become prime minister. Under the pretext of a temple and mosque, he is pursuing a political agenda.’

The novel ‘A Man from Motihari’ also excels in painting a real picture of life in small-town India. Abdullah Khan vividly captures the feel of the Hindi heartland during the 90s and early 2000s, giving readers a peek into the struggles of middle-class youth amidst economic gaps and the emergence of Hindutva influences.

In the novel ‘A Man from Motihari’, Aslam’s journey – the ups, downs, and triumphs – makes him a connected and engaging figure. The author adeptly captures the details of community structures and identities, giving readers a different perspective on a young person facing life’s hurdles.

Aslam faces the difficulties of being a Bihari, a middle-class youth, a Muslim, and someone aspiring to have more global experiences. The author brings these aspects into the story, showing a true picture of the main character’s journey. Khan breaks free from the usual stories about politics, caste conflicts, and self-centred people, offering a new way to look at the state. The book also takes us on a trip through rural India, challenging common ideas about Bihar.

He writes, ‘On a cold afternoon in 1992, in the town of Ayodhya, hordes of volunteers from the Indian Nationalist Party and other right-wing Hindu groups clambered up the domes of the Babri mosque in a frenzy. They were armed with pickaxes, hammers, shovels and iron rods, and they razed the structure to the ground.

I was stunned. I had never expected this would happen in a country like India. Initially, Abba didn’t believe it when the news of the mosque’s destruction came in, and he insisted that it was a rumour. Even the solemn baritone of the All India Radio newsreader couldn’t convince him.

I found my father’s behaviour strange.

But, in the afternoon, while listening to the Hindi service of BBC London Radio in his bedroom, Abba suddenly bellowed, ‘The bastards have demolished the mosque,’ and began to sob. Then he started to slap his forehead repeatedly. I was there, right next to him.

‘Ammi,’ I held his hands tightly and screamed. I feared that Abba had lost his mind.

Within a minute, Ammi came running. Holding Abba by his shoulders, she asked me to fetch a glass of water.

When I returned with the water, Abba was lying on his bed, his eyes closed, and Ammi was rubbing a brown-coloured balm on his forehead. She was also reciting some holy verses and blowing on his head. Ammi gestured to me to be silent. I placed the glass on the windowsill without making a sound and settled on the edge of the bed near the footrest.

Looking at my anxious face, Ammi assured me that everything would be alright by the next morning. She told me that Abba had had similar attacks in the past. She could remember this happening at least three times.

The first was when Abba’s mother had suddenly died.

The second was when a surgeon in Motihari had wrongly diagnosed a simple infection in Ammi’s uterus as an advanced stage of cancer.

And the third time was when India lost to Pakistan 7-1 in the Asian Games hockey finals in 1982.

Thankfully, on all three occasions, he had been back to normal within twenty-four hours.

Ammi did not cook that evening.

That night, I had a dream in which I saw the mosque was saved from destruction by a supernatural being with wings.

Even though Aslam and his family follow the Sufi tradition and are generally open-minded, the Hindu right wing treats them with suspicion and hostility, much like they do with more conservative families. The novel’s attempt to address too many themes simultaneously results in a melodramatic tone, detracting from the authenticity established earlier in the story.

The story also begins with a hopeful start, presenting Aslam, an aspiring writer on the mend from a broken relationship. His accidental meeting with Jessica, a mesmeric figure with roles in acting, activism, and a past in the porn film industry in Los Angeles, lays the foundation for a love story amid the ascent of right-wing politics in India.

As the story progresses to Los Angeles, the narrative encounters a stumbling block. The love story between Aslam and Jessica, while ambitious, falters with an awkward fusion of race, religion, and conservative values. The first-person narrative feels at times like a personal diary, with abrupt halts and strained expressions.

The novel ‘A Man from Motihari’ effectively shows the challenges faced by its main character amid a transforming India. Though the writing style has some constraints, the novel’s dive into identity,

social interactions, and Bihar’s cultural setting adds significant value to literature. Abdullah Khan’s skill in storytelling is evident, urging readers to reconsider their ideas about stories from small towns in India.

The writer is a Bengaluru-based management professional, literary critic, and curator. Views expressed are personal