Infotainers of yore!

Considered to be of ‘divine’ origin, Kathputlis of Nagaur District in Rajasthan served traditionally as a carrier of local history and social mores, alongside being a medium of entertainment, but have now acquired shorter, synoptic forms to adapt to contemporary contexts

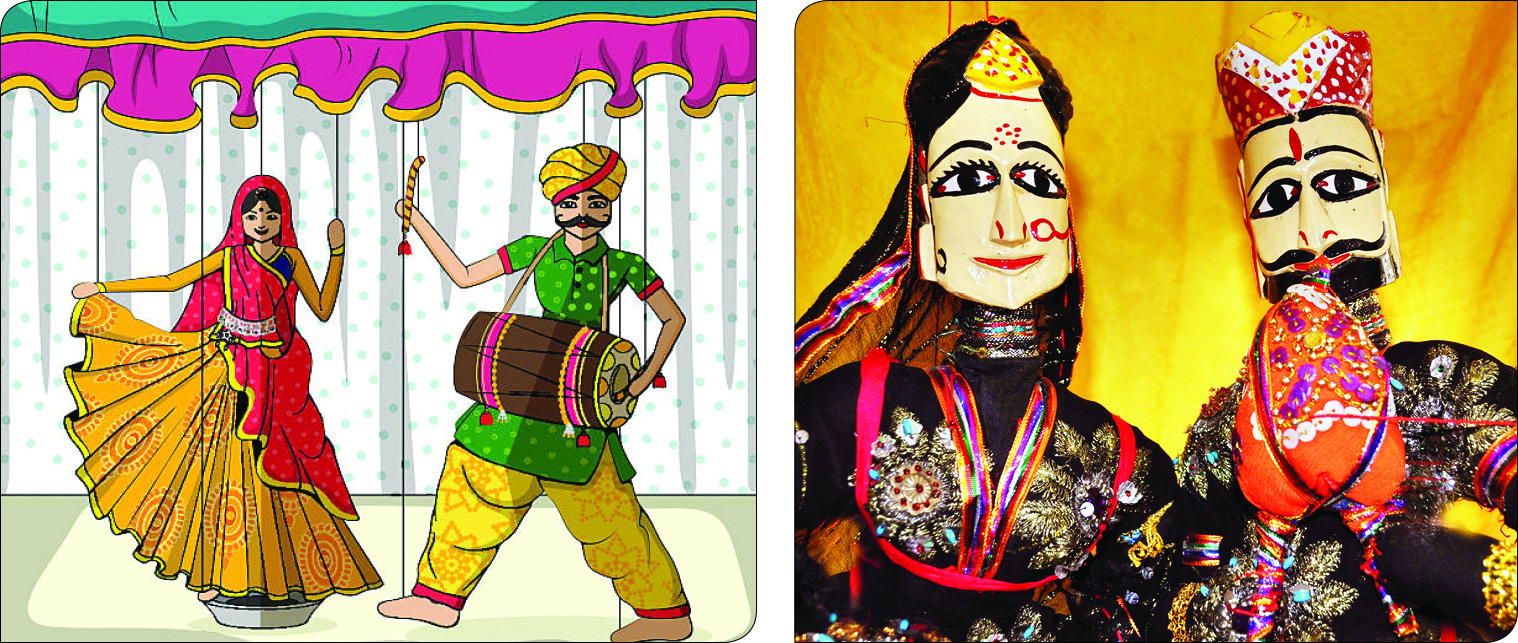

Kathputlis are performative marionettes or string puppets of the Nagaur district of Rajasthan. ‘Kathputli’, which means a wooden doll (‘Kath’- wood, ‘Putli’- doll), received the Geographical Indication tag on the basis of an application filed by the Development Commissioner of Handicrafts, Government of India, in 2008, to mark its unique status as ‘infotainers of yore’.

The practitioners of this craft have shared genealogies, legends, local histories and social mores even as they have ensured that the audience receives its fair share of entertainment. The vast majority of the practitioners are from Nagaur. Though there are two distinct traditions within the community – the ‘Bhats’ who are hereditary bards and genealogists, and the ‘Nats’ who are professional performers — they often work in unison for these occupational categories where rarely clear-cut and often a great amount of overlap existed between these professions.

The puppeteers believe in the divine origin of their art. One belief is that ‘Bhats’ were born out of the mouth of Lord Brahma and, therefore, the entertainment of people is their profession. According to another legend, the ‘Bhats’ always speak the truth, as they are the messengers of the goddess. They claim to have received royal patronage during the reign of the legendary king Vikramaditya, whose life and achievements they extol.

However, their favourite muse is Amar Singh Rathore, the 17th century prince of Nagaur who was himself a great patron of the Bhat community and the ‘kathputli’ tradition. He was exiled by his father, Raja Gaj, in a court intrigue led by his favourite concubine. Amar Singh joined Mughal durbar, and became a ‘mansabdar’ under Shah Jahan, but his sudden rise to prominence and power made the courtiers jealous. Once in an act of provocation, Amar Singh killed Mumtaz Mahal’s brother, after which he was expelled by the court, and became a rebel. After he was captured, his body was hoisted on the tower of the Agra fort, but his childhood buddy Ballu Champawat, along with his band of Rathore warriors, braved all odds to bring back the body to Nagaur where his wives cremated themselves with him on the funeral pyre. This was in the year 1644, and from that time on, this was the principal story of these bards.

However, given the constraints of time (for the original performance would take several hours), shorter, synoptic forms have appeared, and now many other themes, including those of ‘Beti Padhao Beti Bacchao’ and ‘Swach Bharat’, have been incorporated.

The puppets have their stylized marks for easy identification. Thus, the Rajput puppet characters are identified by their moustaches and/or divided beard, while the Muslim characters wear a pointed beard. Besides the courtiers and noble warriors, both Muslim and Hindu, there are female dancers, musicians, magicians, jugglers, horseback and camelback riders, clowns, and other entertainers that comprise a cast reflecting the splendour of Northern Indian courts. There are trick puppets who perform for the court and human audiences – such as the ‘behrupiya’, the double-bodied or head-with-two-faces ‘Kathputli’ that changes from male to female, and the ‘Jadugar’ (magician) that juggles his own head. Another notable character and entertainer are the ‘Sapera’, the snake charmer. After effectively entrancing the snake with his ‘shehnai’ (flute), the snake charmer is bitten and killed by the snake, but is then restored to life when the snake sucks out the venom. And there is the charming dancing girl, ‘Anarkali’, who morphed into Helen in the seventies and Deepika in present times!

The seven steps involved in the making of the ‘kathputli’ include the measurement of wood for the face of the puppet, shaping the face with elongated stylized eyes, the making of the nose, the colouring of the face, smoothening, padding and clothing for puppets – for other than the head, the rest of the puppet is cloth, which is decorated with sequins, beads etc. to make the puppet look attractive.

Rajasthani string puppets are perhaps the only example of their kind in the world where a control or cross is not used for manipulation. In other words, all the strings are attached to the puppeteers’ fingers directly, which demands a great deal of dexterity. The number of strings varies from two to eight depending on the movement and agility of the character: thus, the ‘jadugar’ is manipulated with eight strings, such that at times the puppet holds its heads with its legs, turned upside down, or pulls it’s extended head back into position, making the audience laugh. Anarkali has six strings, and minor characters may have fewer controls.

Traditionally, the set of ‘Kathputliwallahs’ was called the Taj Mahal. The upper front cloth on the proscenium arches was called ‘jhalar’ (fringe); below were attached the arches (through which the puppets were seen) called ‘tibara’; and the black cloth at the rear of the stage (between puppeteer and the puppets) was called ‘kanath’ (a term still used to refer to the appliquéd cloth wall partitions). All three parts were attached to the ‘tent’, called ‘tambuda’ (from ‘tambu’). Prior to the advent of battery lights or power supply, the ‘khandil’ (hurricane lamps/kerosene lanterns) were placed inside the arches on both sides of the front of the stage to illuminate the scene.

These days, the craftsmen have also started making ‘Kathputlis’ as affordable souvenirs for the visiting tourists. They just look like puppets, but have no strings attached for any performance. Thus, all ‘Kathputlis’ are puppets, but all puppets are not ‘Kathputlis’.

Do enjoy the show, and carry the souvenirs home, for the souvenirs not only serve as a fond remembrance, but also add to the economic prosperity of their makers.

The writer superannuated as the Director of the LBSNAA after 36 years in the IAS. He is currently a historian and policy analyst.