Reality check!

The electoral bond system, which is prevalent worldwide in some form or the other, faces continuous scrutiny and a whole lot of apprehensions. As the controversies unfold, the need for greater clarity and accountability in political funding remains paramount

Political fundraising is a complicated process across the world and who can deny that democracy needs elections and elections need money. When the world’s largest democracy held the most expensive national elections spending an estimated $8.7 billion (2019 elections alone), electoral bonds over the last five years accounted for only about $2 billion, representing only a fraction of political funding.

Political finance has long served as the wellspring of corruption in India. For the average Indian, it is hardly breaking news to learn that the murky flow of funds that fuels politicians and political parties largely explains why corruption remains endemic in India. As the costs of elections have soared, politicians — and the bureaucrats under their sway — have mastered the art of steering the regulatory and policy levers at their disposal in exchange for easy campaign cash. Campaign spending is an investment — one that pays back with interest once you are in office.

A political party must build an organisation and mobilise the electorate across the length and depth of its electoral footprint for which meetings need to be organised, people mobilised, doles distributed, advertorials published, volunteers and party workers deployed through various tangible and intangible benefits and all of this costs money.

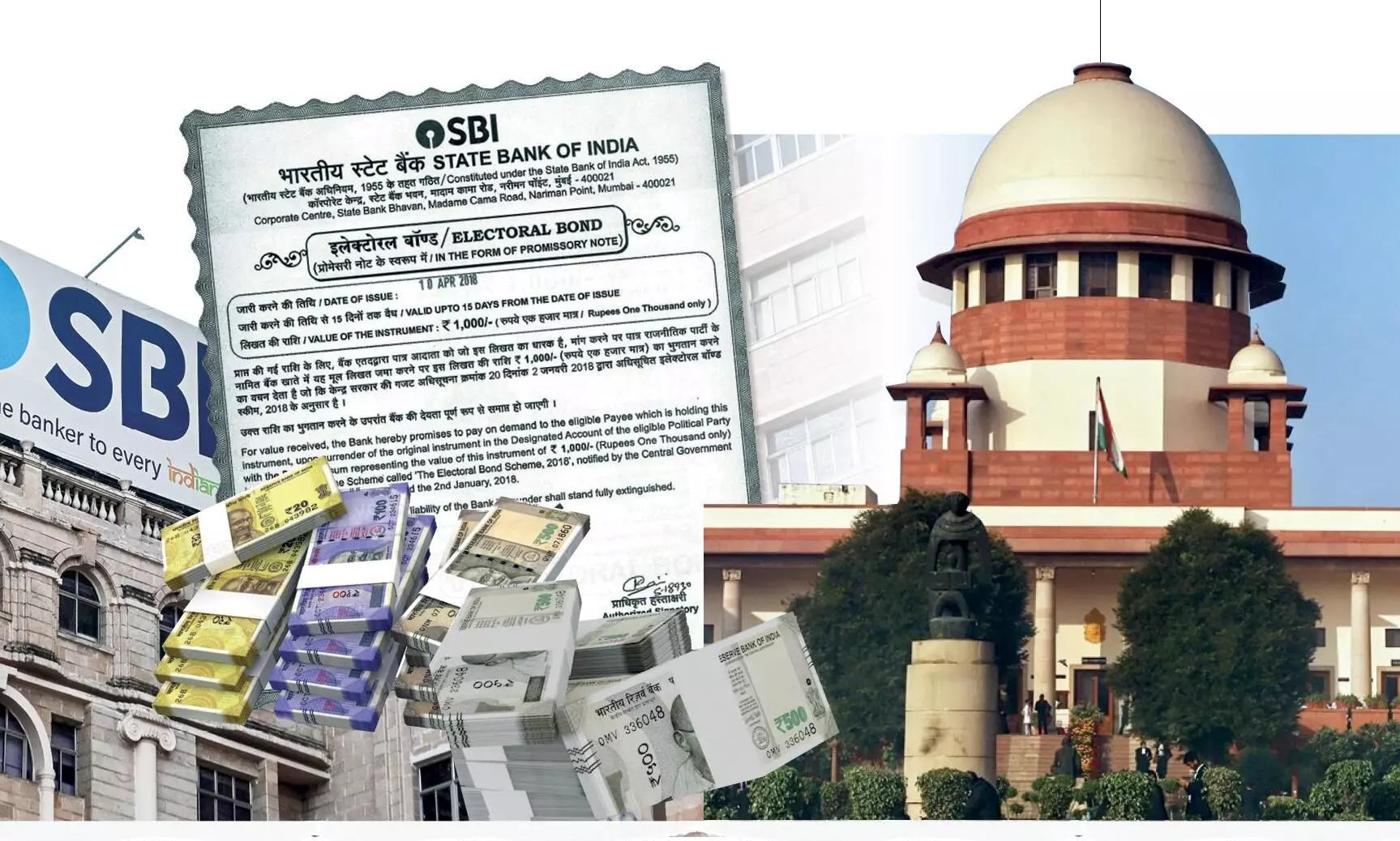

This is where electoral bonds come into play. Electoral bonds are interest-free bearer bonds or money instruments that can be purchased by companies and individuals in India from authorised branches of the State Bank of India (SBI).

These bonds are sold in multiples of Rs 1,000, Rs 10,000, Rs 1 lakh, Rs 10 lakh, and Rs 1 crore. They can be purchased through a KYC-compliant account to make donations to a political party. The political parties have to encash them within a stipulated time.

While there is no doubt that political parties need funds for campaigns and there are many legitimate ways to get them, fundraising can also occur via illegal means, such as influence peddling, extortion, graft, kickbacks, and embezzlement. Different governments have made different policies to limit political funding to legal ways.

Individual donations are allowed in some countries, corporate donations are allowed in others, and there are also provisions in government treasury to fund election campaigns in some nations. Of the 172 countries examined by the inter-governmental group, the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, political funds from corporations cannot be directly passed over to political parties in 48 countries. But, it can be done in the remaining 124.

While private income by corporations can be donated directly to political parties in India, it cannot be done in the US, Canada, Brazil or Russia.

However, there are other indirect provisions to seek political funds in many countries. For instance, Political Action Committees (PACs) or the Presidential Election Campaign Fund in the US provide for the funds used in election campaigns. The Federal Election Commission (FEC) regulates PACs, which are organisations that raise and spend money to elect or defeat candidates.

PACs are not run by parties or candidates. They can be established and administered by corporations, labour unions, membership organisations, or trade associations.

Also, qualified presidential candidates may opt to receive money from the Presidential Election Campaign Fund, which is a fund on the books of the US Treasury. The FEC administers the public funding programme by determining which candidates are eligible to receive the funds. After the elections, the FEC audits each publicly funded committee.

Since political funding has the potential for misuse, the funds must go through a formal banking process. According to the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, out of the 163 countries, political funds do not need to necessarily go through a formal banking process in 79 countries, while in 67 countries, it is mandatory.

In 17 countries, including India and Russia, political funds sometimes move through the banking process.

Of course, political fundraising does not end after elections. The process of returning favours follows thereafter.

“Finance is a necessary component of the democratic processes. However, it may be a means for powerful narrow interests to exercise undue influence,” the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development was quoted as saying, adding that this can lead to policy capture, where public decisions over policies are directed away from the public interest towards a specific interest.

Under a system introduced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government in 2017, people and corporate groups were allowed to donate unlimited amounts of money to any political party anonymously through financial instruments called electoral bonds. Those electoral bonds were gifts — not, as the name might suggest, loans — which donors could buy in set denominations from the government-run State Bank of India (SBI). The donors could then hand them over to any political party which could cash them in at that bank.

The party would know the name of the donor. But it did not have to disclose it to anyone, even the election regulator.

According to some media reports, individuals and companies had bought a total of Rs 165.18 billion ($2 billion) worth of bonds up to

January 2024, according to the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), a non-government civil society group working on election funding in India.

According to the Election Commission of India’s report, the total donations declared by the national parties for 2022-23 was Rs 850.438 crore of which Rs 719.858 crore went to the BJP alone. The government had claimed that “donating money to one’s preferred party is a form of political self-expression that lies at the heart of privacy”.

Furthermore, in 2017, India’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), cautioned the Modi government that the bonds could be misused by shell companies to “facilitate money laundering”. In 2019, the Election Commission of India described the system as “a retrograde step as far as transparency of donations is concerned”.

Since 2018, secret donors have given nearly Rs 16,000 crore (more than $1.9 billion) to political parties through these bonds. Between 2018 and March 2022 — the period analysed by the ADR, a non-governmental organisation – 57 percent of donations via electoral bonds (about $600 million) went to Modi’s BJP.

The Supreme Court of India recently banned electoral bonds, a mysterious source of funding for elections that has generated hundreds of millions of dollars in revenues for political parties.

The court announced its verdict on an ongoing petition calling for the bonds to be scrapped. The scheme has been under scrutiny, and the top court had in November said the bonds “put a premium on opacity” and can be “misused for money laundering”.

The court’s ruling could fundamentally determine how India’s coming general elections, between March and May, are fought; how much of a role untraced money plays in it; and who has the resources to dominate the political landscape.

Some of India’s biggest companies were among the country’s top political funders over the last five years under a now-scrapped opaque political funding system, official data showed.

According to media reports, some of the top buyers of the bonds include — Future Gaming and Hotel Services — the lottery and gaming firm topped the list with a total donation of Rs 13.68 billion ($165 million) between April 2019 and January 2024.

Based in Tamil Nadu, the company, previously known as Martin Lottery Agencies, also has interests in real estate and construction businesses with annual revenues of over $2 billion, according to its website. The company is headed by Santiago Martin, also known as the “Lottery King” of India.

Megha Engineering and Infrastructures Ltd — the Hyderabad-based engineering and construction firm has reportedly bought bonds worth Rs 9.66 billion. Its subsidiary, Western UP Power Transmission, also bought electoral bonds worth Rs 2.2 billion.

Other names include Qwik Supply Chain Private Ltd, Vedanta Ltd, Essel Mining and Industries Ltd, and Bharti Airtel Ltd.

Electoral bonds provide a legal framework for making political donations, thereby reducing the reliance on cash contributions, which are often associated with opacity and potential misuse.

Political parties are required to disclose the funds received through electoral bonds in their financial statements submitted to the ECI. This promotes accountability and enables greater scrutiny of party finances.

However, electoral bonds have also faced criticism and scrutiny from various quarters:

Critics argue that the anonymity of donors undermines transparency and accountability in political funding, as it allows for potential influence peddling without public scrutiny.

While political parties are required to disclose the total amount of funds received through electoral bonds, they are not obligated to reveal the identities of individual donors. This opacity has raised concerns about the potential for quid pro quo arrangements between donors and political parties.

Despite the legal framework governing electoral bonds, concerns remain about the possibility of misuse or circumvention of regulations, particularly in the absence of stringent enforcement mechanisms.

Views expressed are personal