Perseus, Pegasus and the missing Bellerophon(s)

Neither Indian nor international laws could justify the extent of alleged surveillance done through the spyware; legitimate probe at home and collaboration abroad is the need of the hour

As the gruesome murder of Jamal Khashoggi is being linked to the Pegasus operation, it sends a terror down our spines. Pegasus may not have decided the fate of Khashoggi, but such technologies are capable of doing so — and this is enough reason for moving us to caution.

The extraordinarily sophisticated spyware can stealthily sneak into one's phone at ease and control the device to an extent greater than the owner of the phone does! This amounts to limitless spying culture. From the target's business communication to their core personal spaces — everything comes under scanner.

At the centre is a private Israeli company that functions under the supervision of the Israeli defence ministry. The company's flagship product Pegasus — a winged horse in the Greek mythology — is supplied to dozens of countries "for the sole purpose of preventing and investigating terror and serious crime". The Pegasus, once delivered, could run or fly at the whims of its master — the Bellerophon(s)!

So far so good. But the real controversy, as is evident, is the reported use of the spyware against civil societies, journalists and political opponents across the world.

Until now, major players in surveillance have been state-controlled agencies, but now, this new shift indicates another range of private companies that may be defining the rules of the game. Is Pegasus the only, or is there an emerging profit-driven industry?

This is time to retrospect if the surveillance needs of the governments are eclipsing the critically important privacy rights? Do Indian laws approve of such an extensive surveillance activity? If yes, then with what limitations? Who sets the accountability for the manufacturer company and to whom it is answerable?

Background of NSO

The company's name NSO initially stood for the initials of its three founders — Niv Carmi, Shalev Hulio and Omri Lavie. The founders of the company had earlier worked for an Israeli intelligence agency — Unit 8200. The company claims to have a very noble intent — to help government agencies prevent and investigate terrorism and crime to save thousands of lives around the globe.

The products of NSO are export-protected — meaning that the export of its products remains under the oversight of the Defence Export Controls Agency (DECA) of the Israeli Ministry of Defence. The agency very much controls the countries to which the NSO products can be supplied. NSO produces a vast number of products, including Eclipse — a technology that can intercept drones mid-air.

NSO Group sells Pegasus only to governments and law enforcement agencies. As the company claims in its Transparency Report dated June 30, 2021: "Nor do we have any knowledge of the individuals whom states might be investigating, nor the plots they are trying to disrupt, as is otherwise standard amongst our corporate peers." If Pegasus is considered to be a cyber weapon, then this statement runs contrary to the existing provisions of Wassenaar arrangements where a seller of dual-use technology cannot clear itself from the obligations of the use of technology by end-users.

"Pegasus" is the most well-known product of NSO, which may have been used by dozens of countries around the world to collect data from the mobile devices of "specific suspected major criminals". So, basically, this is a form of targeted surveillance. The investigative report claims that Pegasus has been confirmed to be sold majorly in ten countries — Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Morocco, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Hungary, India and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Going by the objective of the company to fight terrorism, do these countries represent the best set to be handed over such a powerful tool?

Indian laws and surveillance

Indian laws allow surveillance in two forms — interception of messages under the Telegraph Act, 1885, and interception of data under the Information Technology Act, 2000. Interception is allowed only in limited circumstances by a competent authority in recorded form.

In exercise of powers conferred by Section 7 of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, the Central Government had, in 2007, amended the Telegraph Rules 1951, to insert rule 419-A after the rule 419.

Rule 419-A, read with Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, provides that the interception of messages by the Central or the state governments must be overseen by a Review Committee. In the case of the Central Government, the committee has to be chaired by Cabinet Secretary and must include Secretary to the Government of India In-charge, Legal Affairs and Secretary to the Government of India, Department of Telecommunications as members.

As per the rule, the Review Committee shall meet at least once in two months and record its findings whether the directions (of interception) issued are in accordance with the provisions of the Telegraph Act. If the committee finds otherwise, then:

Records pertaining to such directions for interception and of intercepted messages shall be destroyed by the relevant competent authority and the authorized security and Law Enforcement Agencies every six months unless these are, or likely to be, required for functional requirements.

More importantly, the direction for interception of messages "shall remain in force for a period not exceeding 60 days from the date of issue and may be renewed but the same shall not remain in force beyond a total period of 180 days."

Now, compare this with the alleged surveillance conducted by the software Pegasus, which is more of continuous nature. Rather than intercepting the messages and calls, it steals away the data of the targeted persons at a scale that is unprecedented and cannot be justified under the laws of our country.

Furthermore, hacking is strictly prohibited under the IT Act. Section 43 of the Information Technology Act provides for penalty and compensation if any person "introduces or causes to be introduced any computer contaminant or computer virus into any computer, computer system or computer network"

Computer containment means any set of computer instructions that are designed to:

to modify, destroy, record, transmit data or programme residing within a computer, computer system or computer network; or by any means to usurp the normal operation of the computer, computer system, or computer network.

The Central agencies that are authorised to conduct surveillance include: Intelligence Bureau, Central Bureau of Investigation, National Investigation Agency, Research & Analysis Wing, Directorate of Signal Intelligence, Narcotics Control Bureau, Enforcement Directorate, Central Board of Direct Taxes, Directorate of Revenue Intelligence and Delhi Police Commissioner.

It must be noted here that there has been wide public debate in the country over the efficacy of above laws in terms of implementation, and compensation and penalties remain insignificant when compared to the scale of snoop that we are witnessing right now.

On the question of privacy, the Supreme Court, in a unanimous judgement on August 24 in Justice KS Puttaswamy vs. Union of India upheld the right to privacy as a fundamental right — the beauty of the judgement being that the nine-judge Constitution bench held six concurring judgments. Whatever be the interpretation, the outright denial of privacy — which is evident from the reporting of the media consortium that investigated the Pegasus matter — is very far beyond what the judiciary interprets from our Constitution.

Justice DY Chandrachud had noted in his judgement: "The right to privacy imposes on the State a duty to protect the privacy of an individual, corresponding to the liability that is to be incurred by the state for intruding the right to life and personal liberty." It is the immediate duty of the Indian Government to institute a probe into the matter — setting up a Joint Parliamentary Committee could be a viable option in this regard. It would also be desirable that the Supreme Court — being the custodian of Fundamental Rights — institute a judicial probe into the matter.

Democracy and surveillance

It will certainly be tempting for any government to have greater control over the communication aspects of its subject. This is where a line is drawn between an authoritative regime and a democratic regime — the degree of control varies as we move from one pole to the other.

Most of the countries associated with the list have shown authoritative tendencies in the past few years or more. This raises a critical question: If NSO wanted to deal with criminals and terrorists, why did it let its technology land in the hands of some of the authoritative nations — where it is most likely to be misused?

The revelations around the Pegasus Project show two kinds of illegitimate surveillance — surveillance over the civil society and media fraternity within a country, and surveillance of state heads, probably across the borders of countries. The names of at least 14 state heads — three presidents, three prime ministers and three ex-prime ministers (when they were in governance) have been exposed till now. While the first kind raises questions around privacy and data theft, the second on sovereignty.

It is left to the readers to decide where does democracy stand if it is compromised on the crucial aspects of individual liberties and sovereignty?

Way forward

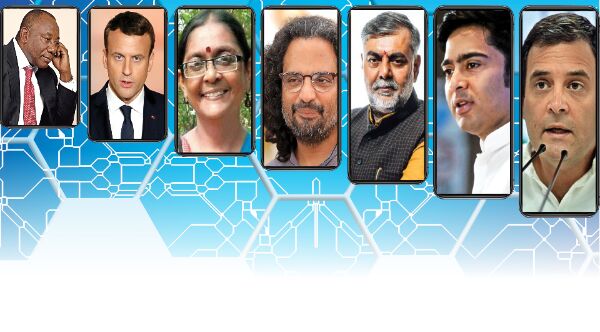

Thanks to the efforts of the media consortium, the issue of illegitimate surveillance has attracted global attention. As an immediate fallout, the Israeli government has announced to institute a task force to look into the matter under immense global pressure. Defence Minister Benny Gantz however threw the buck on customer countries saying "countries that purchase these systems must meet the terms of use." A separate judicial probe has been ordered in France to investigate the hacking of Emmanuel Macron's phone. As the matter progresses, more countries like Mexico, UK etc. are exploring the probe option. In India, as is seen, the matter has taken a complete political turn. Amid the opposition's outrage, there are two extremely meaningful takeaways — a transparent and honest reply to the People of India and, at least an assurance of a probe into the matter.

Apart from this, what is required is a comprehensive framework or treaty regulating the growing industry. Experts stress that such technologies should be considered as cyberweapons, and their transfer and sale be governed in the same manner as war weapons. A system on the lines of Wassenaar arrangement, that has provisions like End User Monitoring Arrangement which sets an accountability parameter for the seller of dual-use war technologies, has to be extended to cyberweapons in a defined manner.

The negative impact of Pegasus was first discovered in 2017 by The Citizen Lab. Either globally, or in India, no visible attempts have been made since then to fix the accountability of the company or to come out with proposals of collaboration around the issue. There seems to be an inertia, or perhaps some ulterior motive, that stops the governments from taking strict measures in this direction.

The Indian government has denied any unauthorised surveillance of civilians on the floor of Parliament — and that has to be respected for the sake of the institution. But what is most absurd is the counter allegation put forward by certain ruling party politicians that there is a global effort to malign the image of Indian government. This obsession needs to be overcome — as the investigation is not targeted towards any particular country. Even the slightest sign that the sovereignty of the nation and the rights of its people are being compromised should prompt the government to take rigorous steps. For the sake of the integrity of the nation, the government should make no delay in coming out of the national image obsession, to take stock of a possible and real threat to national security. The question that should haunt the Indian government is that if it is not using Pegasus in India, who else is?

Conclusion

The revelations have left legal and administrative systems bewildered. The encroachment of privacy rights goes far beyond what the legal provision of countries provides redressal for. In the case of India, where the privacy laws are already criticised for being inadequate and unorganised, the Pegasus threat seems to mock the laws.

The Indian government should initiate a Joint Parliamentary Committee probe into the matter as the real customers of the spyware are not yet identified. The next step should be to upgrade the laws related to privacy and surveillance to incorporate newer threats like Pegasus. At the same time, internationally, there has to be a collaborative initiative to go to the roots of the problem and build a long-lasting comprehensive solution, taking on board veteran technical experts and fresh minds from across the countries.

Fundamental rights of individuals and sovereignty of the nation could not be left to linger if we are to stick to our sacrosanct nature of a democratic state.

Views expressed are personal