Assange’s path to freedom

With Julian Assange walking out free of the Federal Court Building in Saipan, North Marianas Islands after pleading guilty of breaching the US Espionage Act and the court accepting his 62 months already spent in Belmarsh Prison as a sufficient sentence, he will have no more cases to answer and sentences to serve apart from a trail of unanswered legal questions and unresolved controversies

On June 26, Julian Assange walked out of the Federal Court Building in Saipan, North Marianas Islands, a free man. He pleaded guilty to one count of breaching the US Espionage Act.

With the court accepting his 62 months already spent in Belmarsh Prison as a sufficient sentence, he has no more cases to answer, and no more sentences to serve.

Assange is standing on Australian soil, having spent his first night in his home country in nearly 15 years.

His lawyer Jen Robinson, filled with emotion as she addressed a rowdy media pack in Canberra, said Assange’s return home had “saved his life”.

Stella Assange, human rights activist, Julian’s wife, and the mother of their two children, said she could not describe the moment when he rushed from the plane, across the tarmac, and into her arms.

On social media, she offered one simple word next to the photo of their embrace: “home”.

However, this case leaves behind it a trail of unanswered legal questions and unresolved controversies. In particular, there are questions of fundamental human rights that can only now be addressed in future cases, if ever.

Assange has been a fugitive since his organisation WikiLeaks published classified United States military footage it alleged showed the killing of Iraqi civilians and two Reuters journalists by US forces.

For seven years he was holed up in Ecuador’s embassy in London, dodging an extradition order to the US over the leaks, until 2019 when police entered the embassy and detained Assange, placing him in jail where he remained until just days ago.

Since 2012 he has fought attempted extraditions and later charges of violating the US Espionage Act — which carried a maximum penalty of 175 years’ prison.

Very recently, he finally settled a plea deal with the US, pleading guilty to one charge of conspiracy to commit espionage in return for a “time already served” sentence.

Ms Assange told the media he was grateful to all who had supported him, but he was tired and asked the family be given privacy.

“My name is Julian Paul Assange.”

With that, the WikiLeaks founder uttered the first words that the assembled journalists and supporters had heard from him, since the latest – and perhaps final – extraordinary chapter in his legal battle had begun.

In a wood-panelled courthouse, at the foot of a lush hillside on the Saipan coast, Assange waited through three hours of a hearing that would see him plead guilty to violating US espionage law, in a deal that would allow him to be reunited with his family in Australia.

As he entered the court under a blazing blue sky, Assange took no questions from the swarming media – many of whom had flown thousands of miles to this remote American outpost of 40,000 people in the Northern Mariana Islands.

The chief judge Ramona V Manglona opened the proceedings. She noted that the courtroom was unusually packed and asked Assange to confirm what he had done and why he was pleading guilty.

Assange replied that working as a journalist he had encouraged a source to provide classified information and believed the first amendment protected that activity. He was now accepting that it was in fact a violation of the US Espionage Act.

Asked again if he was pleading guilty because he is “in fact guilty of that charge”, Assange took a long pause.

“I am,” he said.

As the unprecedented hearing continued, the judge noted that the timing of it was key to its outcome.

“If this case was brought before me some time near 2012, without the benefit of what I know now, that you served a period of imprisonment … in apparently one of the harshest facilities in the United Kingdom … I would not be so inclined to accept this plea agreement before me,” she said.

“But it’s the year 2024.”

Manglona declared she would accept the terms of the plea deal hashed out between Assange and the US government. Assange was invited to stand before her and receive his sentence, with his time already served in a British jail meaning that he would be immediately freed, with no period of supervision.

“With this pronouncement, it appears you will be able to walk out of this courtroom a free man. I hope there will be some peace restored,” Manglona said.

That this outcome was all but certain the second Assange walked into the courtroom, did little to diminish the impact of the moment. The WikiLeaks founder appeared emotional as he nodded at the judge, acknowledging the verdict.

“It appears this case ends with me here in Saipan,” Manglona went on, asking him whether he understood all the details of the agreement.

Assange replied, now a little hoarse: “I do.” He tightened his tie and held his glasses in his hand as the judge went through the final formalities.

“With that … Mr Assange it’s apparently an early happy birthday to you,” she said.

“I understand your birthday is next week. I hope you will start your new life in a positive manner.” However, some of the legal issues emerging from this case remain tantalisingly unresolved.

Once Assange had formally pleaded guilty, the US government’s lawyers announced they would immediately withdraw the request to extradite Assange from the UK. That means the appeal that would have been heard later this year will not go ahead.

To recap, in May the UK High Court gave Assange the right to appeal the UK Home Secretary’s order for his extradition. This was granted on two grounds, both related to free speech.

The first ground of appeal accepted by the court was that extradition would be incompatible with Assange’s right to freedom of expression, as guaranteed in the European Convention on Human Rights.

The second ground, related to the first, is that he would be discriminated against on the basis of his nationality because he could, as a non-citizen of the US, be unable to rely on First Amendment freedom of speech rights.

But as this appeal is no longer proceeding, the issue of whether a threat to the accused’s freedom of expression can stop extradition will therefore not be argued or decided. The European Court of Human Rights and other human rights bodies have never addressed this point. It’s unlikely to arise again soon.

Also on freedom of expression, the relationship between the US Espionage Act and the First Amendment of the US Constitution remains an open question.

Not to mention, his team has always maintained that the publication of US intelligence was an act of journalism in the public interest, revealing alleged war crimes, and Assange should not have been punished for it.

In the pleadings, Assange and the US government took different views on whether the exercise of freedom of expression should constitute an exception to the offences under the Espionage Act. Nonetheless, Assange accepted that no existing US case law established such an exception.

This leads to the question of whether the guilty plea establishes a precedent for prosecuting journalists for espionage.

In the strict legal meaning of precedent in common law, which refers to a binding judicial interpretation, it does not.

The judge made no determination on whether Assange or the US government was legally correct. However, the US government can now point to this case as an example of securing a conviction against a journalist under the Espionage Act.

The question of how much a non-national of the US can rely on the First Amendment likewise continues to be on the table. This issue would also have been addressed in the extradition appeal, as a question of whether Assange would be discriminated against on the basis of his nationality.

Finally, the hearing revived the question of whether the time Assange spent in the Ecuadorian embassy between 2012 and 2019 counts as detention.

As the judge moved to determine whether the sentence of “time served” was a sufficient penalty for his offence, the US government insisted the judge could only consider the 62 months in Belmarsh.

Assange’s lawyers argued he had been detained for 14 years, including the period claiming asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy. In 2016, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention found Assange was arbitrarily detained in the embassy, largely because of the disproportionate length of time between his initial arrest and the date of the working group’s opinion, over five years.

The UK and Sweden both rejected the working group’s findings, which they do not regard as binding. Furthermore, the findings went beyond the established case law on arbitrary detention, which usually focuses on issues of legality and fair process rather than duration. Only the dissenting member of the Working Group analysed the impact of Assange’s voluntary conduct on the length of his stay in the embassy.

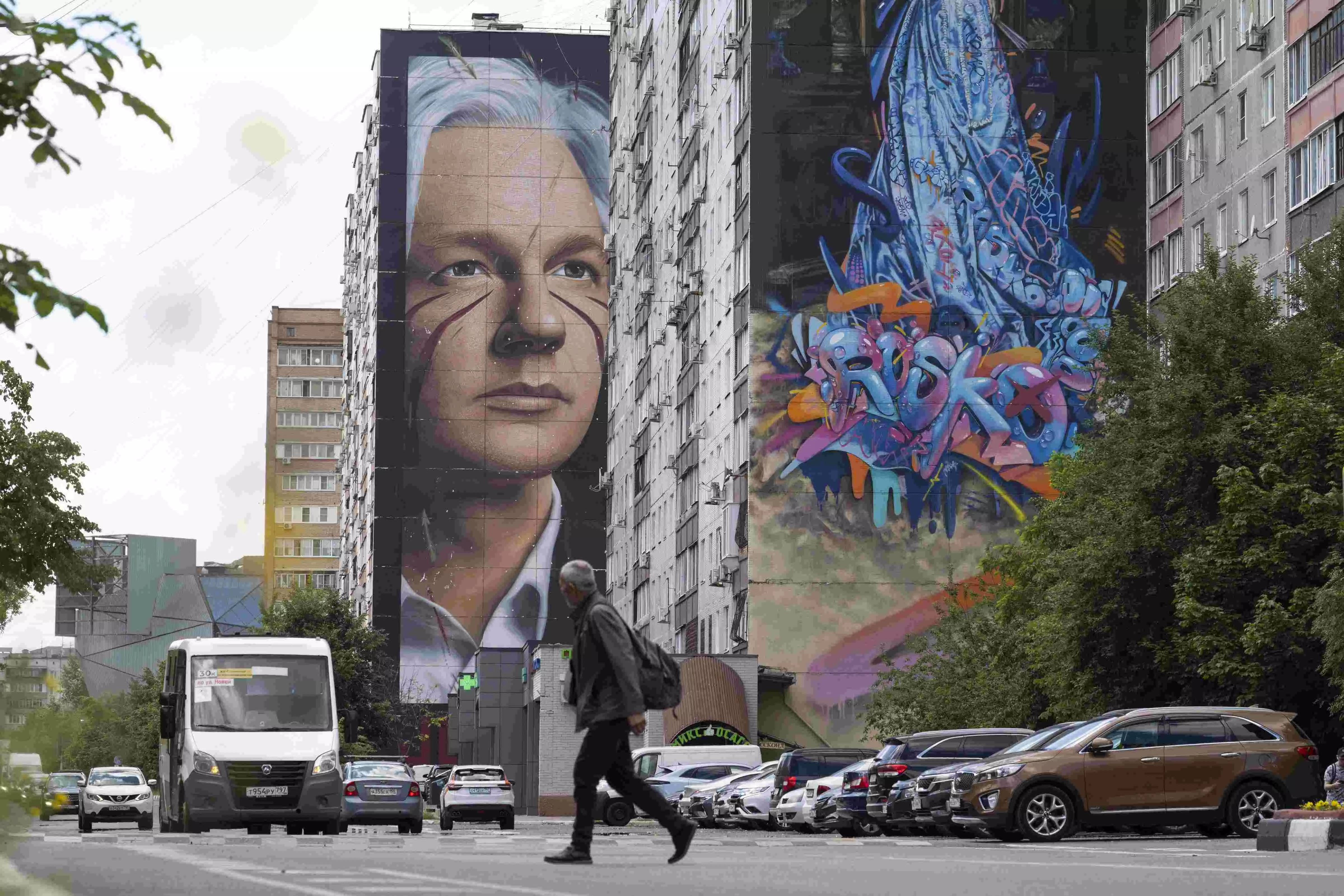

As Assange remains a divisive figure, lauded by some as a champion of free speech and of journalism, and derided by others as a criminal evading justice, in front of the sparkling Pacific Ocean, next to a beach, a 14-year legal saga comes to a surprising and sudden end, half a world away from where it first began, leaving behind a trail of unanswered questions and legal curl-ups for years to come.

Views expressed are personal