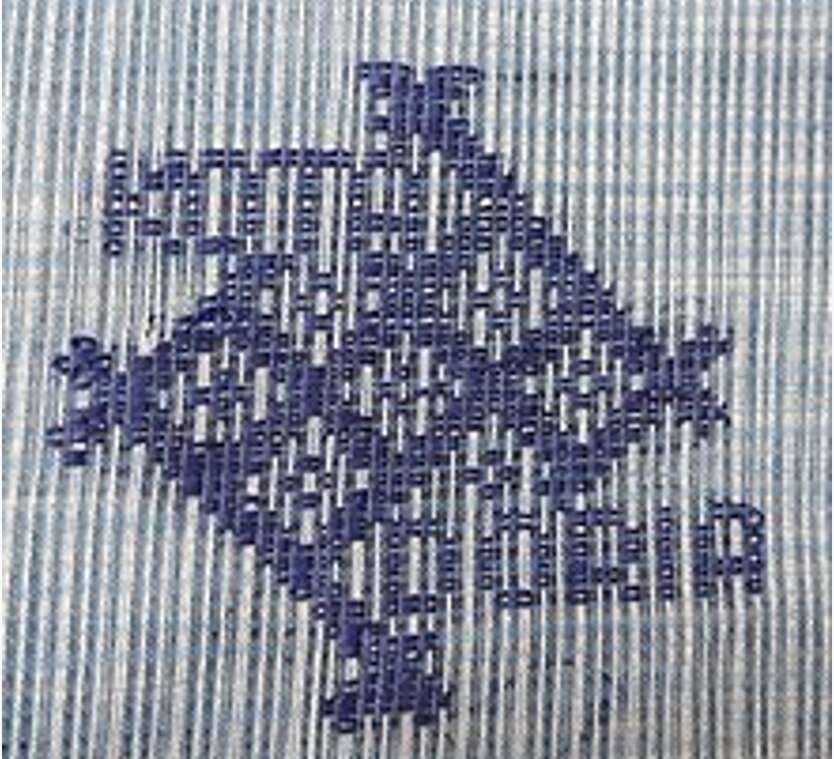

Exquisite patterns

Duplication of GI-tagged Kota Doria fabric which is defined by its check patterns and transparent texture, has stripped the craft’s practitioners of their due reward; a solution needs to be found sooner

The fabric and design which goes by the name of Kota Doria draws its name from the Kota State in erstwhile Rajputana (now Rajasthan). The craft is practised mainly by members of the Ansari weavers' community. While entire families are involved, it is only the men who have the privilege of being master weavers. The main inputs for Kota Doria fabric include cotton, silk, and zari (fine gold threads used for embroidery), woven in different combinations in warp and weft, so that they produce square check patterns. This check pattern is popularly known as 'khat'; and it is this defining feature of the fabric which gives it a transparent look.

The cotton used in production is purchased from Ahmedabad and Nagpur, while the silk comes from Bangalore and Mysore. Zari is procured from Surat. The oldest and biggest concentrations of weavers of Kota Doria are in Kota, Kotsuwan, Kansuwan, Mandana, Sultanpur and Sangod in Kota District; Mangrol, Siswali and Anta in Baran District; and Bundi, Keshoraipatan, Kepren and Roteda in Bundi District.

Plausible origins

There are three competing stories about the origin of this technique. The word 'Masuriya' added to the Kota saris also adds to the mystery. While one view is that the name can be attributed to the craftsmen who came from Mysore, others link the name to the initial use of Mysore silk in the saris. As per one legend, Jhala Zalim Singh brought weavers from Mysore in Karnataka to Kota in the mid-seventeenth century as he was impressed with a characteristic small squared lightweight cotton fabric used for turbans. Since the weavers had come from Mysore, the fabric produced was called Kota Masuriya.

Another version, and a more plausible explanation for the use of word 'Masuriya' is given by noted textile experts, Rita Kapoor Chishti and Amba Sanyal, in their famous book, 'Saris of India' wherein they opine that the Kota Masuriya saris come in a wide variety of checks in pure cotton as well as cotton and silk, with the finest resembling the 'Masoor' lentil seed. They argue that Masuriya has got nothing to do with Mysore.

The main distinguishing feature of Kota Doria is the presence of any of the 'Khat' patterns in the fabric. In itself, the Kota Doria Sari is a plain-woven cloth, either grey or bleached, manufactured wholly from cotton or predominantly cotton along with combination of any other fibre. It has a unique 'corded effect' which is obtained by cramming either the warp or weft threads, or both, or by using threads of different counts to form stripe pattern warp way or weft way. The typical width ranges from 90 to 140 cm and the length ranges from 5 meters to 8.5 meters. The Kota Doria suits and dupattas are plain woven cloth which may be either dyed or undyed using cotton, silk, zari and / or other fancy yarns in the warp or the weft or both with or without 'booties' for the ground and/ or 'pallu' and neckline or any other value addition thereupon.

This unique characteristic of the Doria fabric, produced on handloom, prompted the Kota Doria Development Hadauti Foundation (KDHF) to apply for a Geographical Indication (GI) with the help of the project office of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO). However, in spite of a GI being awarded to this product, the manufacture of an almost visually identical fabric using power looms, especially in Uttar Pradesh, is still quite common. The power loom fabric also sells in the market as Kota Doria but for a much lower price, thus driving down the demand for authentic Kota Doria, a label which should by law only be used for the mentioned handmade fabric from Kota. Therefore, the economic condition of the practitioners of the craft is not commensurate with the exquisite skill sets which they command.

In a comprehensive study of the sector, CUTS has opined that a possible solution to reduce the asymmetry in the sector would be a reorganisation of the value chain to one that is more buyer-driven rather than producer-driven. Buyer-driven chains are those in which end-buyers (typically retailers or supermarkets) establish particular standards and practices for their suppliers and products, and organise the distribution channel accordingly to meet those specifications. This will ensure that producers are aware of what product would sell in the market. CUTS study has recommended that high-end retailers such as FabIndia and Anokhi could play an important chain organisation role by working directly with weavers to supply their stores with high quality, made-to-order products under a fair-trade type scheme and/or as part of each company's corporate social responsibility (CSR) policy — adding value both for buyers and producers alike.

Views expressed are personal