Mystique & musicality in poetry

Composed in traditional Bengali music forms, the verses in Bhanusingher Padabali—penned by Rabindranath Tagore under the pseudonym Bhanusingha—brim with the intense romantic fervour of Radha-Krishna love and are infused with the poetic affinity and spiritual ethos of Brajbhasha

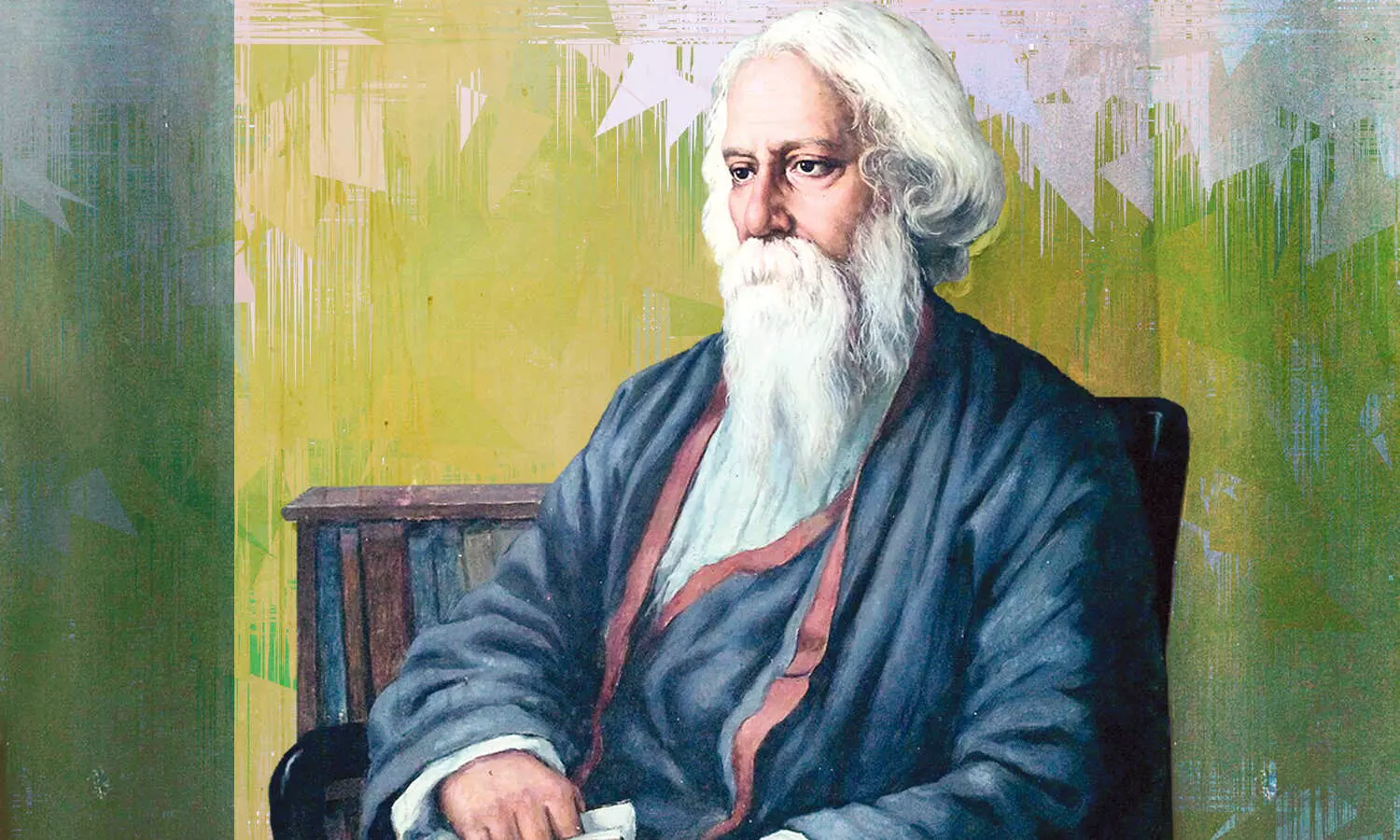

“Gahana kusuma kunja maajhe, mridula madhura banshi baaje…” (In the lush embrace of a flowery grove, a tender melody of a flute gently whispers through the air...). These were the words hastily written by 16-year-old Rabindranath Tagore, on a slate, one cloudy afternoon. Filled with joy upon penning these lines, Tagore eagerly shared them with someone he knew wouldn’t comprehend a single word, nevertheless, appreciate it. And that exactly happened. Rabindranath Tagore recalls in ‘Jiban Smriti’ (My Reminiscences) the circumstances in which he began writing ‘Bhanusingher Padabali’. He says, “One afternoon, the sky suddenly darkened with dense clouds and filled me with impulsive delight. Lying on my bed I bent over a slate and wrote in chalk…” (the above-mentioned poem). He infused his poetry with the intense romantic fervour shared by Radha and Krishna. He passed them off as the writings of a famous Vaishnav poet, whose manuscript he chanced to find in the family library.

The appreciative response to ‘Bhanusingher Padabali’ surprised Rabindranath, who, during his formative years, displayed a deep fascination for the poetic works of luminaries such as Jayadev (renowned for his contributions to Bengali literature), and simultaneously drew inspiration from the Maithili verses and philosophical tenets espoused by the legendary Vidyapati. Moreover, Tagore’s creative landscape was further enriched by his immersion in the profundity of Braj/Brij bhasa (a language that was descended from Shauraseni Prakrit), the dialect of the Brij region (of Uttar Pradesh), famous for its poetic fervour and spiritual ethos.

However, it was the eighteenth-century English poet Thomas Chatterton, who wrote under the pseudonym ‘Rowley’ and which (perhaps) inspired Tagore to use the pseudonym Bhanusingha — a name given to him by his sister-in-law Kadambari. Interestingly, Bhanu means the sun, and is synonym for Rabi (Rabindranath Tagore is known as Rabi Thakur in Bengal). Bhanusingha soon delved into themes of mysticism, particularly within the framework of Vaishnavism, weaving intricate verses that embraced the timeless Radha-Krishna motif.

‘Bhanusingher Padabali’ — a series of verses — represents a significant facet of Rabindranath Tagore’s literary repertoire, showcasing his profound engagement with the musical and poetic traditions of Bengal. Tagore was deeply influenced by the Bhakti and Baul (Sufi wandering singing minstrels) traditions of Bengal. Drawing inspiration from these mystical and devotional traditions, Tagore embarked on a creative journey to express his spiritual experiences and philosophical insights through poetry and music.

‘Bhanusingher Padabali’, a testament to Tagore's profound connection with nature, love, and spirituality, encompasses a diverse range of themes, reflecting his multifaceted worldview. Rooted in the cultural ethos of Bengal, these compositions blend elements of love, longing, devotion, and existential reflection, resonating with the universal human experience. Set to traditional melodies known as ragas, they express themes of divine love, yearning, and surrender, drawing inspiration from the Vaishnava tradition. Tagore’s verses invite listeners to contemplate the complexities of existence and embark on a spiritual journey. Through various traditional Bengali musical forms like Baul, Bhatiali, and Kirtan, infused with his distinctive melodic and rhythmic patterns, Tagore created a captivating aesthetic experience that transcends linguistic and cultural boundaries, ensuring enjoyment for generations to come.

Tagore openly acknowledged the profound impact of Vaishnav Padabali — a period in medieval Bengali literature from 15th to 17th century, marked by an efflorescence of Vaishnava poetry, often focusing on the Radha-Krishna legend — on his work. He credited its “freedom of metre and courage of expression” for shaping his boldness in youth. He closely engaged with ‘Prachin Kabya Sangraha’ (old lyrical poems), a collection of Vaishnav poems compiled by Akshay Chandra Sarkar and Sarada Charan Mitra — both close to his family. Thus, it wasn’t a coincidence that young Tagore was drawn to Brajboli.

Rabindranath Tagore found the Maithili-dominated language both challenging and intriguing. In his memoir, ‘Jiban Smriti’, he expressed that despite its initial incomprehensibility, mastering it became a compelling pursuit. He believed that by diving into this unfamiliar linguistic realm, he would unearth a multitude of poetic treasures waiting to be discovered.

In his book, ‘Clearing a Space’, Amit Chaudhuri explores how, during Tagore’s composition of the ‘Bhanusingher Padabali’ (published in 1884), Bengal experienced a surge in intellectual activity. Poets like Chandidas and Vidyapati’s works emerged, inspiring Tagore to create similar resonance through Bhanusingha. This period, from 15th to 18th century, marked the Bengal Renaissance, characterised by a vibrant cultural and artistic resurgence. Scholars, poets, and artists converged, exploring new ideas and expressing creatively, fostering a rich intellectual ferment in Bengal’s landscape.

About that discovery of Vidyapati’s lyrics, Rabindranath once wrote: “Fortunately for me, a collection of old lyrical poems composed by the poets of the Vaishnava sect came to my hand when I was young. I became aware of some underlying ideas deep in the obvious meaning of these love poems…The Vaishnava poet sings of the Lover who has his flute which, with its different stops, gives out the varied notes of beauty and love that are in Nature and Man”.

Tapati Dasgupta, in his book ‘Social Thought of Rabindranath Tagore: A Historical Analysis,’ also suggests that Tagore’s affinity for Vaishnavism stemmed from its representation of India’s authentic culture. He valued its departure from excessive intellectualism, emphasizing love and devotion to a personal God over abstract speculation.

Krishna Dutta and Andrew Robinson in their paper, ‘Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man’ (Bloomsbury Publishing, 1997), emphasise that “Rabindranath Tagore’s exploration of the Bhakti and Baul traditions of Bengal deeply influenced his creative endeavours, leading to the emergence of Bhanusingha as a pseudonym for his song-poems.”

Bhanusingher Padabali, consisting of just 22 songs, stands as a timeless beacon in Bengal’s cultural realm, revered for its spiritual depth and artistic brilliance. Its songs, cherished through generations, inspire poets, musicians, and enthusiasts alike. This collection preserves Bengal’s literary and musical heritage, ensuring its relevance today. Its enduring appeal transcends generations, echoing through the voices of artists across epochs. This work by Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore is a cornerstone for artists, musicians, and scholars, reflecting the enduring power of creativity.

His legacy reminds us of art’s ability to uplift and unite, highlighting its transformative impact on humanity.