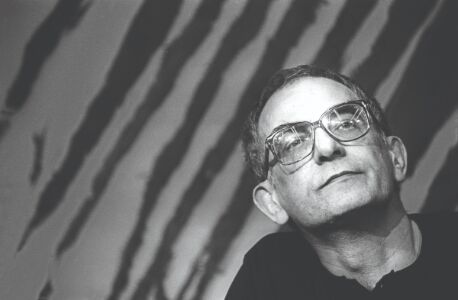

Looking back at Kieslowski

Exploring the style and themes used by Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieslowski through analysis of four of his many iconic works

A closed-door retrospective of four films by the outstanding Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieslowski was recently held in Kolkata. The films were 'Camera Buff' (1979), 'No End' (1984), 'A Short Film About Killing' (1988) and 'A Short Film About Love' (1988). Taken separately, each of these films stands out in its distinct identity, self-complete unto itself, independent of the need to be clubbed together to study the filmmaker as an auteur. They appear to be distinct in some senses, even a unique way of presenting point-of-view films by a filmmaker. At the same time, though they do not reflect a film school per se, they do reflect the filmmaker in terms of his growth, against varying shades of the political context within which he made them.

Kieslowski began his journey in cinema with documentary films after he graduated from Lodz School of Cinema and Theatre in 1969. In fact, his first step into feature films was made with caution when, even as a student, in 1967, he made 'Concert of Requests' in black-and-white that had a running time of just 17 minutes. After making some more documentaries and television dramas, Kieslowski's second feature film 'The Scar' came in 1976 with a running time of 76 minutes. The constant conflict between individual freedom and state control finds itself reflected in his earlier films. The most concrete and ideal example of this is 'Camera Buff'. The film is about a father who buys an 8mm camera to film his new-born baby. His interest and skills with the camera motivated his boss at the factory where he works to commission him to make a film documenting the daily working lives of the factory workers at home and at work. He feels he has found his oeuvre in filming a human document instead of making a document which would place his bosses in a good light. In the meantime, his marriage breaks up and his wife walks out with the baby. By this time though, Filip, the hero, is too involved with the process of filmmaking. This visible shift in priorities comes across tellingly in one shot where he frames his wife with his fingers joined to resemble the frame of a camera lens as she walks out. She turns around at the last minute to find him recoil.

He is constantly obstructed in his filmmaking. The final hit comes when in an indirect act of attack, the factory director sacks his boss instead of sacking Filip. In disgust, Filip exposes the entire film he made right out on the streets. But his chosen destiny takes over, and the closing shot finds us watching him turn the camera on himself, narrating the story of his life right into the camera. You are left wondering – is this film, is this film 'Camera Buff' made by Filip Mosz? Is Mosz Kieslowski's alter ego? He is, and you begin to understand the psyche of a filmmaker. 'Camera Buff' underlines the fact that filmmaking is not an ivory-tower, elitist vocation as it was understood to be at the time this film was made. The film is a pointer to the truth that filmmaking can and should equally be a vocation one comes into by accident rather than by a process of conscious choice which of course, is also an option. And that it can grow from the grassroots where an identity crisis, a crisis of choice can make or mar a creative artist's life and art.

'No End' (1985) on the other hand, is a story narrated from an unusual point of view of a successful lawyer who has recently passed away. It has two major strands of content. One is that of an unfinished case the dead lawyer had taken up on behalf of a factory worker. The other is that of Antoni (the lawyer)'s wife Ulla's attempts to cope with her husband's sudden death. The second strand soon overshadows the first and Ulla's troubles begin to dominate the narrative. The fence-sitting tactics of the legal and judicial system in Poland during the Emergency in 1981 comes across movingly in the film. Cinematically brilliant in technique and form, 'No End' is somehow reflective of Kieslowski's disturbed state of mind symbolised in the defeatist, even fatalistic approach of Ulla to her tragedy. As she puts her head inside the gas oven, she does not realise that in the very process of trying to reunite with her husband through death, she triggers another tragedy that is bigger than her own — the tragedy of leaving an orphan behind to fend for himself.

The allusions to death are as omnipresent as life itself, made so tellingly that one almost begins to believe in it as fact, which it is not. But content-wise, this critic did not quite care for the ruthlessness in Ulla's character towards herself, towards her son, paint her in negative shades and make her all-abiding love for her dead husband appear like her obsessive lover for herself projected onto her husband. 'A Short Film About Killing' (1988) and 'A Short Film About Love' (1988) were made within his famous 'Decalogue' which are ten films in all that are the director's personal interpretation of 'The Ten Commandments' as seen and shown through the struggles of ordinary people in Warsaw. These two films are reinterpretations of the fifth and the sixth commandments. These films were made by Kieslowski, both for Polish television as well as for the large screen, a unique feature of the time. 'A Short Film About Killing' shot in black-and-white, is shocking in the impact it makes with the cinematic filming of murder for seven long minutes of screen time. It demonstrates the brutal process of killing for its own sake without motive almost, or at most, a concocted motive created through a perverted sense of revenge. Because it is made in black-and-white, it is starker, more striking, more devious and more lasting in its impact on the viewers than it would have, had it been shot in colour.

Though Kieslowski would insist that he never made political films, the fact remains that even from his individualistic standpoint where man is forever alone and isolated from the world he resides in, his camera has never been able to capture neutrality in any sense. Obviously, since the tools and techniques of filmmaking are products of a prevailing ideology, either in support of it or against it, questioning, criticising, arguing.

Our cultural experiences are complex and this complexity can never be reduced and fit into the rigid contours of readymade solutions and 'filmic' conventions. Nor can it have a simplistic relationship with some of the fixed political and ethical answers that we come up with for the troubled world. Nowhere is this complexity and the diverse nature of this very complexity more evident in the works of Kieslowski than in his post-'Decalogue' period of films, on killing and on love are sterling examples of this reality.

In 'A Short Film About Love', Kieslowski approaches the question of isolation, loneliness, alienation through a strange and unusual story of love that evolves between a 19-year-old boy and a woman on the house opposite which he lives, as he watches her clandestinely taking in several men and making love to them. He uses a pair of binoculars to play 'Peeping-Tom'. But over a period of time, these two come together. It is more their loneliness that brings them together than love, which perhaps never was. In the final analysis, they cling to their loneliness through the ploy of voyeurism, a clutch they cling on to, in their separate isolation. This isolation, however, is distanced — emotionally, culturally and cinematically from the displacement one has observed in the films of Antonioni and carry the distinct imprint of Kieslowski's command over the art and craft of filmmaking.

There are marginal slices in these Kieslowski's films that are not very noticeable but are distinct for the director's humane way of presenting things. In 'Camera Buff', for instance, there are the characters such as the neighbour who asks Filip to film his mother. When the mother dies, he asks Filip to screen the film for him. He says that it is his way of making his mother come alive for that moment. He soon leaves the neighbourhood and his place is taken by another man.

In 'No End', there is this American who spends one night with Ulla who takes money for sleeping with him. It is a brief, very brief sketch of a character who has a tender heart hidden behind a brash, brazen front.

In 'A Short Film About Killing', the photograph of the little girl offers an insight into the mind of Jacek, the killer who has never been able to get over his sister's death in a tractor accident. This simple photograph offers the scope of becoming a sort of trigger for the strategic turn in Jacek's life, snuffed out in five minutes flat. The landlady, or Tomak's absent friend's mother, who he lodges within her high-rise Warsaw apartment is another case in point in 'A Short Film About Killing'.

The uniqueness of Kieslowski lies in that he does not offer rules-governed solutions or questions that address contemporary issues in modern life. He never allows analysis of his subject-content to become an end in itself instead of remaining a creative tool for the filmmaker. As he reveals through his films, the underlying cultural structures of the society he looks at, he never loses view of the film as a structure unto itself.

His later films like 'The Double Life of Veronique' and the trilogy 'Three Colours Blue, White and Red' showed a shift in his manner of expression and style and also approach towards cinema probably because he was making these films

In 1994, after his last film 'Red', the final film was screened at Cannes, Kieslowski announced his retirement from filmmaking. It was a pity in the sustaining environment at that time when Hollywood blockbusters had come to dominate world cinema to the exclusion of the cinema from the rest of the world. His last films which were also most commercially successful were foreign co-productions, made mainly with money from France and in particular from Romanian-born producer Marin Karmitz. Sadly, Kieslowski passed away barely two years following his voluntary retirement from filmmaking.

Views expressed are personal