Ungrateful Turnaround

Balaji Huddar’s ideological volte face under communist influence reflected his distorted loyalties, which led him to vilify his former mentor Doctorji, who stayed true to his benevolence

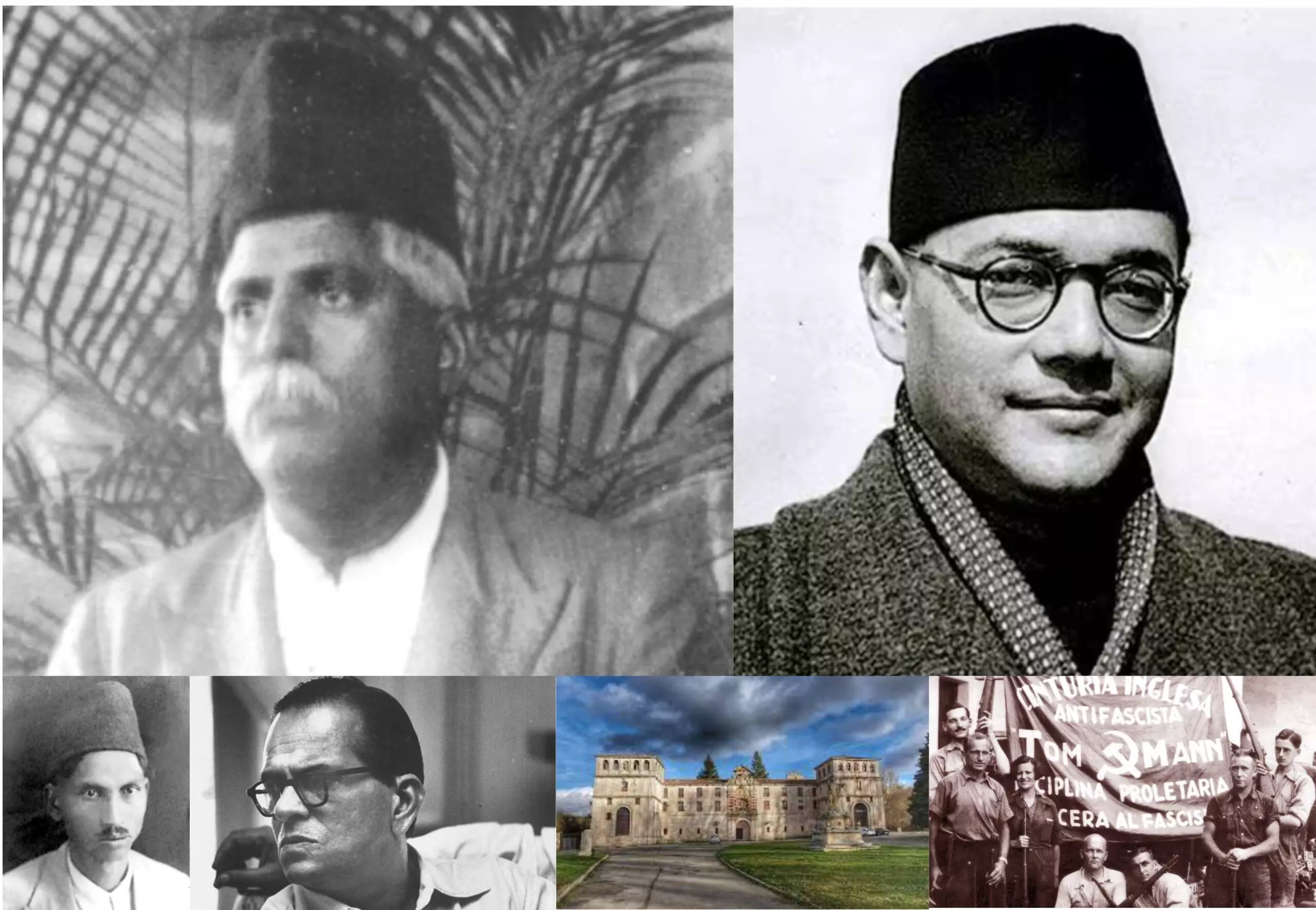

Balaji Huddar’s transformation is a stark example of how communism distorts one’s thinking and approach. HV Seshadri writes, “By the end of December 1938, Balaji Huddar, a close friend and associate of Doctorji in former days, returned from Spain. Doctorji had taken great pains to send him to England, from where he had gone to Spain. When, however, he returned to Bharat, he had turned a leftist. But it made no difference so far as Doctorji’s friendly attitude towards him was concerned.”

Seshadri notes how Huddar himself once reminisced “about this trait of Doctorji in an emotional strain”. Huddar recalled how a “spirit of genuine friendship formed the secret of Doctorji’s success. He was at once one with others – whatever their views or age. And he would maintain that friendly spirit till the very last. Even with my differences of opinion with him, never once did the thought of breaking my bond of affection with him crossed my mind. Such was Doctorji.”

In fact, observes Seshadri, “Doctorji even arranged a talk by Huddar to the Swayamsevaks of Nagpur in 1938 to narrate his experiences abroad.” In sending Huddar to England, Doctorji thought, writes Nana Palkar in his ‘Man of the Millennia: Dr Hedgewar’ that “it would be beneficial for the Sangh if an intelligent, young, and determined Sangh karyakarta could visit a few independent states, observe their civilisations, and return to the Sangh with this deeper insight.”

Huddar’s personality and oratory skills always impressed Doctorji and he was naturally delighted that Huddar was returning to India. Palkar writes that Huddar reached Nagpur on December 24, 1938 and “Doctorji went to the railway station to welcome him. Thereafter, they met on several occasions, but Doctorji realised that Balaji Huddar’s views had completely changed. Nevertheless, Doctorji did not change his approach towards him.” Huddar, on his part, spoke of the “most exceptional feature” of Doctorji’s nature which was his ability to “preserve and propagate the values of friendship…”

Huddar, we know, had been to Spain as part of the International Brigades which were composed of communist activists who were intent on fighting General Franco’s forces. They were self-styled anti-fascist fighters being heavily funded by the Soviet Union through the Comintern and NKVD, Stalin’s secret police, and the French Communist Party in support of the short-lived republican government. Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Nazi Germany supported Franco’s forces. By the autumn of 1936, writes American historian John Toland (1912-2004) “one of Hitler’s concerns was Spain. Small but significant quantities of German supplies and personnel had already been delivered to Franco, and the Führer considered giving more substantial aid. A special air unit capable of providing vital tactical air support” for Franco’s forces was made operational and eventually Hitler “in concert with Mussolini, recognised the Franco regime as the legal government of Spain.” Huddar as an agent of the Comintern sponsored International Brigades was arrayed on the other side.

Historians of the Spanish Civil War, Len and Nancy Tsou, write in an article, ‘Gopal Mukund Huddar: An Indian Volunteer in the IBs’ (2016), that Huddar joined the IB in 1937 and to “shield his Indian lineage changed his name to John Smith.” Huddar, they write, “went to England to study journalism, where he witnessed the powerful international solidarity for the Spanish people’s fight against fascism.” While in England, Huddar “began attending meetings and rallies addressed by communists and other progressive speakers. His mind further shifted away from RSS’s Hindu nationalism.”

While in Spain, Huddar was among those arrested by Franco’s forces and imprisoned in San Pedro de Cardena, an ancient monastery that was reopened and converted into a prison for International Brigade activists. Huddar’s co-prisoner was an American communist Carl Geiser (1910-2009) of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. In his memoirs of life in the San Pedro monastery-prison, ‘Prisoners of the Good Fight: The Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939’, Geiser mentions Huddar and his giving lectures on “the struggle for independence from Britain of the people of India under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru.” By a stroke of luck, Huddar escaped death in Franco’s prison and was freed under a prisoners’ exchange agreement between Britain and Spain.

Len and Nancy Tsou argue that Huddar’s “experience in the International Brigades and its underlying Marxist philosophy had made a huge impact on him. In 1940, he joined the Communist Party of India (CPI) and began to work for the cause of peasants and labourers in the countryside around Nagpur.” In later years, Huddar would often regale young Marxist cadres with his exploits in the Spanish Civil War. It is not surprising, if one keeps in mind Huddar’s complete subservience to communism and to its world view, that in later years he forgot and forsook Doctorji’s values of friendship and compassion towards him, and indulged in heaping calumny on his erstwhile mentor by weaving a false tale around his and Subhas Bose’s meeting that could not materialise.

His indoctrination and complete surrender to communist methods of subterfuge made the same Huddar write lines against Doctorji such as, “Shrewd as he was” Hedgewar, “took the hint and stretched himself on the bed saying ‘Balaji, I am really very ill and cannot stand even the strain of a short interview. Please don’t” and hinted that Doctorji was not interested in fighting the British or in meeting Subhas Bose. “As I left the room, the RSS volunteers entered and laughter broke out again.” (‘The RSS and Netaji,’ Illustrated Weekly of India, 7 October, 1979).

Huddar deliberately and mischievously played down the fact that by 1939 Doctorji was actually suffering from prolonged bouts of illness and exhaustion and that he would be dead by the summer of 1940. Wedded to a diabolical political creed which props itself up on false propaganda, Huddar, in later life, sought to buttress his communist credentials by trying to paint his first and only genuine mentor and friend, in a false light. Huddar’s falsehood has been latched on to by leftist propagandists who pass off today as academics and authors.

Let us return to Subhas Bose and the communists. It is important to recall their role in abusing the former, since they now claim to have been his real comrades and paint the RSS as British collaborationists. In his thought-provoking biography of Subhas Bose, ‘Deshnayak Subhas Chandra’, educationist and historian of Bengal renaissance, Nemai Sadhan Basu (1931-2004), writes that even during the Swaraj party days, Indian communists were opposed to Subhas Bose. In fact, while they also opposed Mahatma Gandhi, the communists were more rabidly opposed to Subhas and the Swarajists. Delivering his presidential address at the AITUC’s Calcutta session on July 4, 1931, Subhas was forthright in his warning that one should not submit to any foreign institution or to Moscow’s dictates and denounced the communists’ propensity to cling to the apron strings of Moscow.

In his study of facets of the freedom movement, ‘Swadhinatar Mukh’ (Face of Freedom), historian Amalesh Tripathi (1921-1998), discusses the attempt by Indian communists to wage a separate trade union movement under instructions from Moscow and of how Subhas Chandra had resisted it arguing that the “Moscow Communists are a serious menace to the growth of healthy trade unionism in India and we cannot possibly leave the field to them.” Subhas, argues Tripathi, wanted the Indian trade union movement to turn into an instrument for achieving India’s freedom and not be reduced to becoming a weapon for Stalin.

By 1942, that is within two years of the passing of the Pakistan resolution in Lahore, when the second world war raged and Subhas was waging a valiant struggle against the British from outside India, Indian communists shamelessly abused him. Savour a few samples, here. BT Ranadive (1904-1990), then an influential member of the CPI’s Central Committee, abused Subhas as a “henchman of Japanese imperialism” and a “future dictator.” Terming the INA a mercenary army of “rapine, loot and murder,” Ranadive referred to communists as “honest patriots” while speaking of Subhas and his followers as “traitors and Quislings.”

The writer is a member of the National Executive Committee (NEC), BJP, and the Chairman of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal