Tongues on Fire

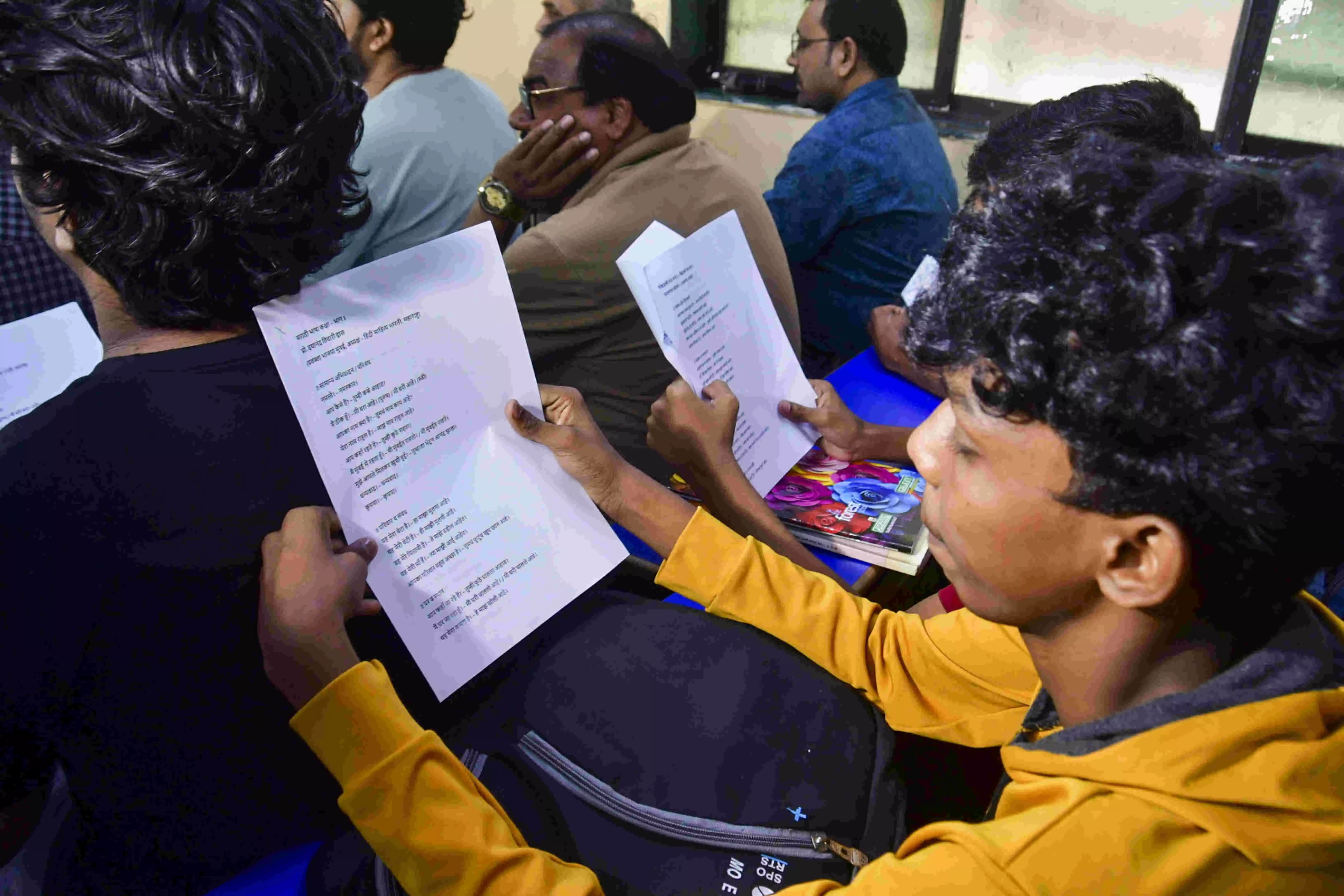

The frequent language-related confrontations across India have reignited old tensions, raising concerns about coexistence and national unity in a country known for its rich linguistic and cultural diversity

The ghost of linguistic unrest of the 60s seems to haunt the country once again. Unfortunately, the last few months have seen frequent incidents of violence in Maharashtra and Karnataka over the perceived domination of other languages over the regional languages, sparking a strong feeling of ‘insiders’ versus ‘outsiders.’ In February, tensions mounted in the Belagavi region, known for its mixed Kannada and Marathi-speaking population, resulting in violent clashes and vandalism. In April, two women were assaulted in Thane for speaking English instead of Marathi. Last month, a sweet shop vendor in Mira Road, Mumbai was allegedly assaulted for not speaking in Marathi, and early this month, a migrant auto-rickshaw driver in Palghar was beaten for asserting that he would only speak in Hindi. Similarly, an investor’s office was vandalised over his post on X that he would not learn Marathi despite living in Mumbai for 30 years. Controversy erupted when a lady Bank Manager of SBI in the Chandapura branch in Bengaluru refused to speak Kannada, saying, “This is India, I won’t speak Kannada.” In 2023, the Kannada Signboard Protests turned violent, with vandals targeting establishments for not using Kannada prominently (at least 60 per cent of signage as mandated by law).

Language evolved as a medium of communication which helped the evolution of various social, religious, and political institutions in the world. A language signifies the unique socio-cultural identity of people in a geographical context with emotional overtones. Nevertheless, in spite of the numerous languages spoken in the world, political and economic institutions have transgressed linguistic boundaries as humans learnt to live in harmony with mutual respect and cooperation. Learning a language is an asset, for it widens one’s perspective and opens the doors to various opportunities.

However, language has also been a trigger for violent agitations across the world. For example, the 1952 Bengali language movement against the imposition of Urdu in East Pakistan (today’s Bangladesh) culminated in the 1971 Bangladesh independence war, claiming around 3 million lives. In Turkey, the suppression of the Kurdish language (spoken by 15 per cent of the population) has fuelled unending ethnic conflict. Over 500 languages are spoken in Nigeria, with Hausa, Yoruba, and Igbo being the major ones; tensions have led to periodic violence and ethno-linguistic clashes, like the Hausa-Yoruba tensions. The Biafran Igbo secession (1967–1970), which caused 1 million deaths, had linguistic roots. In Spain, tensions exist between Spanish (Castilian) and regional languages like Catalan, Basque, and Galician. The Catalan and Basque regions often push for linguistic autonomy; the Catalan independence movement in 2010 saw widespread violent clashes. In Canada, the Quebec separatist movement led to referendums in 1980 and 1995, though violence has been rare. In Belgium, the Dutch (Flemish, 60 per cent) versus French (Walloon, 40 per cent) divide is glaring but generally peaceful.

It is perplexing to see linguistic tensions surface even in today’s India when films from both Bollywood and Tollywood are doing roaring business all over the country, and the cuisines of both South and North have become equally popular across India. When the iconic movie ‘Sholay’ of the 70s ran for a year in Madras (today’s Chennai), a huge fan following for Rajnikanth became evident even in the northern belt; Bahubali, Pushpa, RRR, et al. have become household names in the North. Today, cricket has transcended linguistic boundaries, with players and fans drawn from all over the country, and the business runs in crores. One can go on counting various aspects of cultural and linguistic synthesis between the North and South, which is a true blessing for the unity of India. At the end of the day, it all seems to boil down to a ‘love and hate’ syndrome with sporadic outbursts rather than an outright antagonism among people on linguistic lines.

However, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do,” they say. It is intriguing that people living in a state for years refuse to speak the local language with the people of that state. But at the same time, acts of violence and vandalism are equally reprehensible. A sense of proportion is also expected from the agitators with regard to establishments where the use of Hindi or English is necessary, such as central government offices, the banking sector, hospitality sector, postal department, aviation and transport sector, etc. Respect for local language and culture is an uncompromisable principle. As far as possible, settlers in a state must try to communicate in the local language with the people of that state. Refusal to do so only reflects juvenile chauvinism. For example, it would be ridiculous to imagine Indians settled abroad insisting on speaking only in an Indian language with people out there—no less than expecting people in those countries to learn such Indian languages to communicate with Indians in their own land.

The framers of the Constitution had the foresight to visualise linguistic discord in the country and accordingly provided for the Eighth Schedule to honour linguistic diversity and to prevent one single language from dominating. Hindi was given the status of ‘official language’ (Art. 343) alongside English, but not as the ‘national language’. The original list in 1950 included 14 languages: Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Malayalam, Marathi, Oriya (now Odia), Punjabi, Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu. Later, through amendments to the Constitution in 1962, 1992, and 2003, eight more were added: Sindhi, Konkani, Manipuri, Nepali, Bodo, Dogri, Maithili, and Santali—making it a total of 22 regional languages.

As per Census 2010, Hindi is spoken by 52.83 crore (43.63 per cent), Bengali by 9.7 crore (8.03 per cent), Marathi by 8.3 crore (6.86 per cent), Telugu by 8.11 crore (6.70 per cent), while other major languages like Gujarati, Tamil, Kannada, Malayalam, and Urdu are spoken by people ranging between 3 crore to 6 crore respectively, each with distinct cultural identities. As a counterweight to the numerical strength of Hindi, the Eighth Schedule specifies different regional languages for official use in government, Parliament, judiciary, and education so that a balance is maintained among all languages. The Schedule supports the development and preservation of the listed languages through the promotion of literature, education, and official use. However, promoting Hindi as a common language is a constitutional directive (Art. 351), but of course not by imposition. We need cooperation and consensus in this regard, as opposed to confrontation.

Whatever the triggers may be, it is unfortunate that language wars are surfacing again at a time when India is struggling hard to address more serious issues such as poverty, unemployment, healthcare, climate change—not to mention terrorism, which is pushing our defence preparedness to the edge. Moreover, if linguistic tensions persist, they will hamper growth by depriving people—and the entire economy—of economic opportunities. Migrant workers, who struggle to make ends meet, can be the worst victims. If not addressed in time, these linguistic tensions may potentially endanger the national unity which the framers of our Constitution laboured hard to ensure. It is the responsibility of all citizens to cultivate tolerance and extend cooperation to one another irrespective of language, faith, or culture to live up to the intent of Article 19. Political leaders should prefer constitutional methods to address their genuine concerns rather than play to the gallery. Surely, we do not want to prove Churchill right on his racist remarks that “once independence is given, Indians will fight amongst themselves for power and India will be lost in political squabbles.”

The writer is a former Addl. Chief Secretary of Chhattisgarh. Views expressed are personal