Statecraft Over Politics

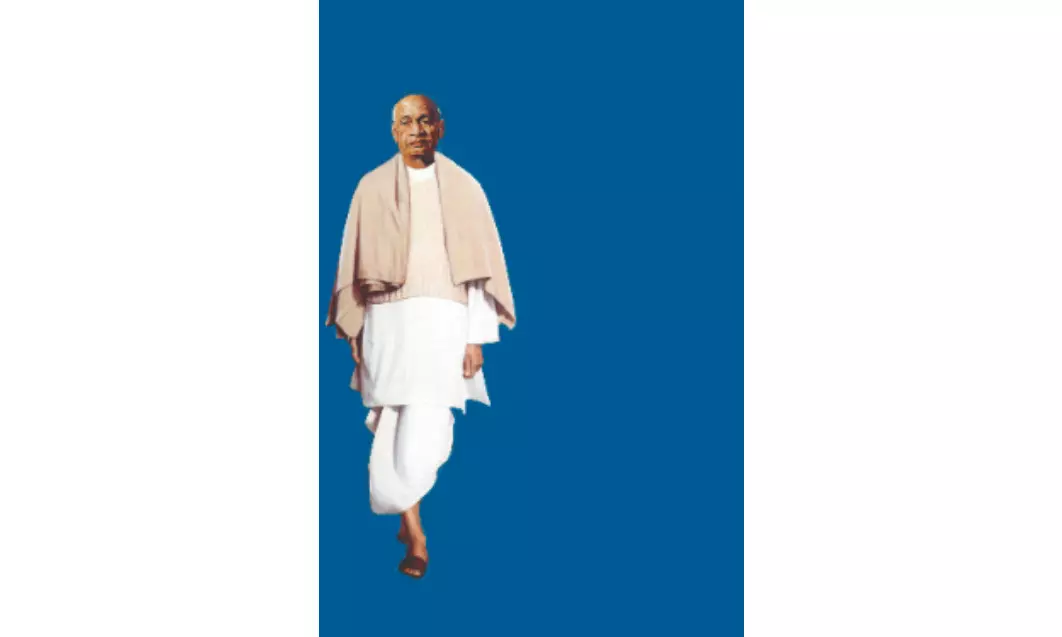

As India looks to 2047, Sardar Patel’s vision of a neutral, ethical civil service offers vital lessons for rebuilding the steel frame of governance

Independent India will reach its centenary in 2047, a milestone that coincides with the launch of Vikshit Bharat and a renewed commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals. This second-generation nation-building effort unfolds within a neoliberal framework, and the government has introduced Mission Karmayogi to nurture a civil service steeped in Indian ethos. In this evolving architecture, bureaucracy remains the pivotal engine of progress, a role that Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel envisioned when he helped lay the foundations of the Indian administrative system. Mission Karmayogi, with its emphasis on digital empowerment and ethical leadership, seeks to translate Patel’s ideals into a contemporary governance model.

A Colonial Legacy and the Need for a New Ethos

The Indian civil service still bears the imprint of its colonial past, a fact that even Patel noted when the British left in 1947. The machinery they bequeathed was designed to extract revenue, not to serve a democratic polity. Patel, who had witnessed its excesses as a lawyer and freedom fighter, argued that simply inheriting the old structure would be insufficient. Today, the nation celebrates the 150th anniversary of his birth and the towering Statue of Unity, yet tribute alone will not be enough. Patel believed a service rooted in Indian values could become the “steel frame” that holds the nation together, provided it shed its colonial veneer and embraced public service. Moreover, Patel’s contributions to the Constituent Assembly debates highlighted the need for an administration that would protect the unity of a newly independent nation.

Defining the New Indian Administrative Service

Despite initial reservations, Patel became the strongest advocate for retaining a civil service—though not in its British form. In his 1947 address at Metcalfe House, he described the existing Indian Civil Service as “neither Indian, nor civil, nor imbued with any spirit of service.” He proposed its redesignation as the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), arguing it would be wholly Indian, tasked with administering a unified nation. For Patel, service meant “service to the nation, service to the people, service for achieving the objectives of the nation,” a principle enshrined in the Constitution. He envisioned a merit‑based, politically neutral institution protected by Article 311, capable of functioning without fear of arbitrary dismissal. The IAS training academy at Mussoorie was later established to inculcate these values, emphasising integrity, empathy, and a deep sense of national purpose.

Upholding Unity and the Political Neutrality of the Service

Patel recognised that a robust All-India Service was essential for safeguarding India’s unity after independence. He championed constitutional safeguards, especially Article 311, to guarantee civil servants’ political neutrality. He urged officers to act as faithful agents of the government, free from partisan allegiance, and insisted that political considerations be minimised in recruitment, discipline, and control. In correspondence with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Patel warned that excessive political interference would erode the developmental state. This conviction led him to support a statutory Civil Services Board to insulate officers from day-to-day political pressures, ensuring the bureaucracy could rise above regional, linguistic, and sectarian divides. The All-India Services continue to play a crucial role in coordinating policy implementation across states, a testament to Patel’s foresight.

The Imperative of Independent Thought and Compassion

Patel encouraged civil servants to speak frankly and offer independent advice. He famously allowed his secretary to submit a note opposing his views and advised officers such as V. P. Menon, V. Shankar, and H. V. R. Iengar to reflect independently. Beyond intellectual honesty, he stressed compassion for the poorest, urging officers to be accessible listeners for ordinary citizens. In a 1949 letter, he wrote, “Your power lies not in the authority you wield but in the service you render to the humblest of the land.” Patel believed a civil servant should be a bridge between government and the governed, understanding the lived realities of farmers, labourers, and marginalised communities. Regular field visits, he argued, would keep the bureaucracy grounded and prevent it from becoming a detached elite.

The Corrosion of the ‘Steel Frame’: A Warning Ignored

Patel’s warnings remain relevant. Frequent transfers are now routinely used to secure political compliance, despite Supreme Court directives advocating fixed tenures. Reports from the Administrative Reforms Commission (2008) and the Sixth Pay Commission show the average IAS posting lasts barely sixteen months, eroding morale and effectiveness. Ministers often focus on transfers rather than substantive policy, undermining the neutrality Patel cherished. Political patronage has seeped into recruitment, with lateral entries sometimes bypassing merit‑based examinations. The proliferation of ad-hoc bodies and parallel structures has fragmented the administrative landscape, diluting the authority of the traditional civil service. These trends have led to delayed projects, inconsistent policy enforcement, and a growing trust deficit between citizens and the state. If left unchecked, they risk weakening the very cohesion that Patel helped forge.

Learning from Sagacity in the Developmental State

As India strides towards Vikshit Bharat, political interference and corruption threaten the integrity of our administrative machinery. Patel’s experience as a lawyer, freedom fighter, and integrator of the princely states offers a blueprint for a competent, ethical, and people-centric civil service. While a perfect separation between politicians and bureaucrats is neither possible nor desirable, curbing undue interference is essential for achieving developmental goals. By embracing Patel’s vision—rooted in service, neutrality, and compassion—we can reinforce the “steel frame” that has underpinned India’s progress for generations.

Mission Karmayogi, with its focus on capacity building, ethical leadership, and digital empowerment, provides a contemporary vehicle to translate Patel’s ideals into practice. If policymakers heed his counsel—ensuring fixed tenures, protecting merit, and fostering a culture of fearless advice—the bureaucracy can once again become the reliable engine of a thriving developmental state. In doing so, India will honour the legacy of its first Deputy Prime Minister and lay a sturdy foundation for the next century of nation-building, one that is inclusive, sustainable, and truly Vikshit.

Views expressed are personal. Fr Felix Raj is the VC, and Prabhat Kumar Datta is an Adjunct Professor of Law and Public Administration, both at St. Xavier’s University, Kolkata