Serendipity on a Highway

A roadside tent of books on Imphal’s NH-37 becomes a space of wonder, nostalgia and healing—reminding us how the unexpected can return us to what we cherish

“I love walking into a bookstore. It’s like all my friends are sitting on shelves, waving their pages at me”

Tahereh Mafi

Serendipity is the act of discovering something good purely by accident. It could be an old five-hundred-rupee note in the pocket of a freshly washed shirt or an unexpected new discovery while searching for something else. Either way, such discoveries more often than not are happy happenings, as human memory is notorious for misplacing and/or ignoring what we hold dear, even when they are always somewhere nearby!

I have been trying out different ways of shedding weight in recent years. After a failed tryst with the gym, where one had to lift weights to lose weight and also risk sudden cardiac arrest on the treadmill, I took to walking—a harmless pastime without any nasty surprises. And it was during one such recent expedition, as I walked down the path next to the busy National Highway 37, which weaves through Imphal, that I made a serendipitous discovery which reunited me with my first love—books.

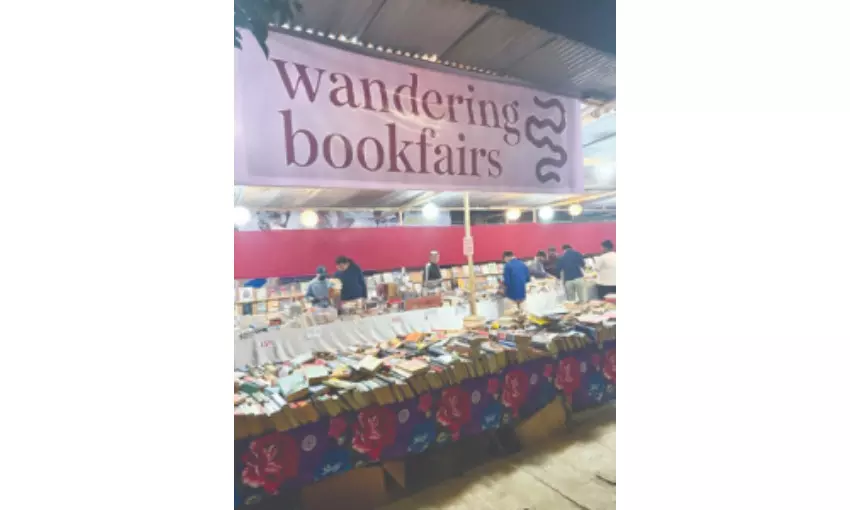

A tent with temporary tin roofs had been set up on the roadside, under which a dozen or so wooden tables were laid out. As far as I could see, there were books—some neatly stacked, others jostling for space, cover to cover. I had stumbled upon, in the middle of Imphal city and on the side of one of its busiest roads, a wandering book fair!

There was no entrance gate or security guards with bomb detectors. It was like a street food stall selling books instead of food. In fact, just across the highway was Imphal’s famous and popular street food market. For foodies and bookworms, the coincidence of these two co-existing close to each other, however temporarily, was a double delight.

A voracious reader in my younger days, I had, over the years, found myself drifting away from books. Reading had worked on me like an antibiotic for most ills. The company of words had a soothing, placebo-like effect on my nerves. If Wodehouse reminded me that life can be carefree and sunny, others like Thomas Hardy could shock you with dark plots and insidious relationships. Magazines were devoured like buffets offering a hundred different dishes on the same table. I read James Hadley Chase and Pearl S. Buck with the same fascination, without judging either, as both opened windows to different winds from outside. To me, books are “portable magic,” as Stephen King once called them—travelling across lands and minds, leaving on each reader they encounter some lesson, some memory and a little bit of magic.

But I soon descended into reading files and notes, records and data, memorandums and gazette notifications—a hell that scarred my soul with its indifference and detachment.

And then I stumbled upon this gold mine. Not having encountered so many books in a long time, I moved slowly from table to table where old familiar faces looked back at me with accusing eyes, as if asking where you have been.

A Jane Austen classic here, a set of hardbound Shakespeare there; Three Men in a Boat waving from a world forgotten; childhood fantasies of nosing around with the Famous Five and the Secret Seven; thrillers by Dan Brown and Chase; Archies in leather-bound sets; Leon Uris reminding us of the birth and pain of Israel—the collection seemed to pander to every taste and more.

I spotted a book titled Recipes Inspired by Jane Austen by Robert Tuesley Anderson, inviting the reader to relish Cassandra Austen’s Scrambled Eggs and R. Wodehouse’s All Spoke Tarts. In another corner lay Mike Brearley’s Spirit of Cricket—notably missing nowadays. An interesting find was J. K. Rowling’s The Casual Vacancy. There was even a small pocket-sized book containing the sayings of Donald Trump, which no doubt many years from now will be read with the solemnity it deserves.

New books came with handy discounts, and second-hand ones were sold by weight. I had either read or at some point owned or borrowed many of the familiar titles on display. But the charm of good books is that one can read them a hundred times and continue to be mesmerised just as the first time. It was like meeting ghosts from the past who had never left. I found myself once again mingling with Grisham, Carroll, Twain, Conrad, the sisters Brontë, Asterix, Tintin, Uris, Austen, Shakespeare, and so many other faithful friends of yore. And there were local writers I had not had the pleasure of reading, like Sonia Oinam and Rajesh Konsam, who no doubt are already fellow travellers to many readers.

Then there were the blind-date books hidden in large envelopes. Many would have discovered that blind dates with books end more happily than those with fellow humans!

Mr Damodar, a pleasant-looking and articulate young man, is the brain behind this endeavour. He started the fair some two years back, and it now travels all over the Northeast, having covered around thirty locations already, with the next stop being Dimapur. This was a student collective initiative brought together by a common love for books and reading. Youths like Kenoshore, Clinton and Nichol, manning the sales counter, were volunteers. Damodar is mentoring the youngsters to take over the travelling book fairs so that he can move on to other projects.

Manipur is a land of some of the most creative minds in India who have thrived in times of strife—be it in performing arts, literature or weaving magic with fabrics. One can see glimpses of their creative talent existing alongside their grit and courage, both in the valley and the hills.

Toni Morrison called books “...a form of political action... knowledge and... reflection...” which can change your mind. It goes to the credit of Damodar and his team that local enthusiasts are thronging the open-air, makeshift roadside book fair and, in a way, healing the wounds of troubled times by turning to books and opening their minds and hearts to worlds beyond their own borders. And therein lies hope for change.

Views expressed are personal. The writer is a retired Civil Servant