Road to Communal Polarisation

Political hesitation in 1937 fractured Bengal’s fragile unity, allowing communal narratives to dominate and reshape the province’s social fabric on the eve of independence

In his extensively documented study “Bengal Electoral Politics and the Freedom Struggle: 1862-1947”, historian Gautam Chattopadhyay (1924-2006) points out that “as soon as election results were known, efforts started to form a coalition Ministry in Bengal.” The Krishak Praja Party leaders “took the initiative in forming a ministry with Congress support” and “this joint effort led to the formulation of a commonly acceptable programme for the guidance of a Congress-supported KPP Ministry, to be headed by AK Fazlul Huq. KPP leader Dr R Ahmed and Prof Humayun Kabir were at the forefront in trying to stitch this alliance. Ahmed recalls how “The All-India Congress leaders, including Jawaharlal Nehru, were extremely unhelpful and Bengal missed a golden opportunity of rallying the Muslim masses to a fighting united front against Imperialism. “It was a cursed day for Bengal”, Ahmed lamented.

Hindu support played a role in Huq’s victory and helped him defeat the League’s formidable candidate Khwaja Nazimuddin (1894-1964) from Patuakhali in Barisal. Nazimuddin represented the landed Muslim elite, which the League promoted politically. In his political biography of Fazlul Huq, “Pakistan Prostab O Fazlul Huq” (Pakistan Resolution and Fazlul Huq) veteran historian Amalendu De (1929-2014) refers to Suhrawardy’s observation that Nazimuddin would not have lost to Fazlul Huq “but for the support which Mr Fazlul Huq received from the Hindus and certain other interested parties.” Speaking of the 1937 provincial elections in Bengal, De observes that this election had defeated the reactionary forces represented by the League, and it was natural for all right-thinking people to expect that the Krishak Praja Party and the Congress would jointly lead Bengal on the right path. People wanted Bengal liberated from the grip of communal forces. Huq himself approached the Congress for help and support, but the Congress’s central leadership refused to sanction a Congress-Krishak Praja Party coalition in Bengal.

By aligning with the Muslim League, argues historian Anil Chandra Banerjee (1910-1990) in his study “A Phase in the Life of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee: 1936-1947”, Huq, “did not realise that he was digging his own grave” and “by March 1938, as many as 34 out of 36 members elected on the KPP ticket had deserted Huq.” By 1938, the sole KPP member in the cabinet, Syed Nausher Ali (1891-1972), was removed based on an unproven charge that he “was not working in harmony with his colleagues and was intriguing with the Opposition.” A reconstituted cabinet had all Muslim members from the League. The “Muslim League”, observes Banerjee, “rapidly consolidated its position in Bengal. The prime organiser was HS Suhrawardy, the most ambitious and ruthless operator among the Cabinet Ministers.” Huq had been increasingly reduced to a figurehead.

With the ascendancy of the Muslim League, Islamist forces began having a field day. The Muslim League unleashed them on Calcutta University. It was a citadel that they had not yet been able to control. A mix of Islamist radicals and the Muslim League’s student front, hurling the cry of “Islam in danger”, opposed the “Lotus” and “Sri” as part of the University emblem. They had built up opposition to it since 1936. The men in power, says Anil Chandra Banerjee, “aided by the Governors and the British officials, hurt the Hindus in all directions.” The Hindu Ministers, Syama Prasad Mookerjee rued, “could hardly exercise any restraining influence.”

Syama Prasad had also earned their ire by encouraging the conducting of the Matric examination in the mother tongue. He was physically attacked while on a college inspection tour in East Bengal’s Chittagong. As he alighted the train, and was about to be greeted by the teachers and college officials, Muslim League hoodlums, yelling “Allah-O-Akbar”, hurled lathis aimed at Syama Prasad. Sinha records that educationist and future education minister of India, Humayun Kabir (1906-1969), who had joined the University of Calcutta as a professor of philosophy in 1933, and was accompanying Syama Prasad, darted to his defence absorbing the blows.

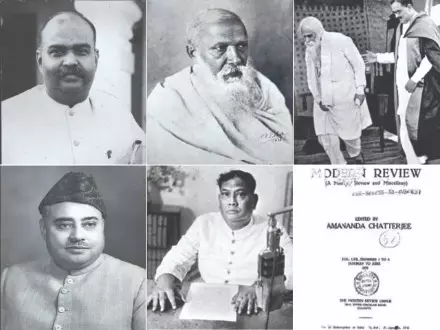

Writing in the Modern Review issue of December 1937, for instance, Ramananda Chattopadhyay (1865-1943), doyen of Indian journalism and a leading icon in the cultural recovery of Bengal, pointed out that “some Mussalman writers found nothing idolatrous in the ‘lotus-sri’ symbol.” But these moderate Muslim cultural and literary voices saw their space shrinking.

In February 1937, Syama Prasad had invited Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore to deliver the convocation address at Calcutta University. It was for the first time that the convocation address was being delivered in Bengali and that too by someone of the stature of Tagore. The Muslim League called for a boycott of the convocation. Most of the Muslim League ministers abstained from speaking in protest when Tagore spoke. They also provoked Muslim students into boycotting Gurudev’s address. It did not matter to these raucous and violent Leaguers that among the many new initiatives and projects that Syama Prasad had launched at the Calcutta University was the initiation of a department of Islamic History & Culture. With the Muslim League dominating, Syama Prasad’s tenure was not renewed, and he retired as Vice Chancellor in August 1938. He had become too uncomfortable for the League-dominated Bengal government.

The Muslim League’s rabid attitude towards “Vande Mataram” was a pointer to the political climate of Bengal during the period when Syama Prasad, the educationist, was transforming into Syama Prasad the political leader. 1938 was Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s centenary year. The seer-bard’s immortal ode, “Vande Mataram”, had become the anthem of the Indian freedom movement and had evoked a Pan-India appeal.

Historian Sabyasachi Bhattacharya (1938-2019) writes in his “Vande Mataram: the Biography of a Song”, that “the most famous of the nationalist poets who helped propagate Vande Mataram was Subrahmanya Bharati (1882-1921). It is reported that Bharati translated the song first in 1905 for a periodical, and a second time in 1908 when a collection of his works was published under the title Jatiya-Gitam. The novel Anandamatham appeared in Tamil translation in 1908 and in another translation in 1919.” Bhattacharya records that as early as 1897, it was translated into Marathi and Kannada, a Gujarati translation appeared in 1901, Hindi in 1906, Telugu in 1908, and Malayalam in 1909. Indeed, long before the Muslim League was established and cut its political teeth, Vande Mataram was a national phenomenon and had spontaneously acquired a national status.

As Ramananda Chattopadhyay argued in the pages of the Modern Review issue of November 1937, “This song has been used at public gatherings, including the Congress, practically as a national anthem, for more than three decades…Those who have practically accepted it as a national anthem have done so spontaneously…” With the song, Ramananda, observed, “are associated the memories of innumerable deeds of heroism and sacrifice and of true stories of daring and suffering the cause of freedom. It is not only Bengalis or Hindus who were inspired by “Bande Mataram” to such deeds and suffering, but non-Bengalis and Mussalmans also were similarly inspired…”

The Muslim Leaguers, its Urdu-speaking elite, refused to accept this historical reality. They wanted a reason to oppose the freedom struggle, and found in Vande Mataram a convenient alibi.

Views expressed are personal. The writer is a member of the National Executive Committee (NEC), BJP, and the Chairman of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation