Quintessentially democratic

The evidence of existence of social institutions like ‘sreni’ and ‘samgha’ in ancient India substantiate the claim of the country being the ‘Mother of Democracy’

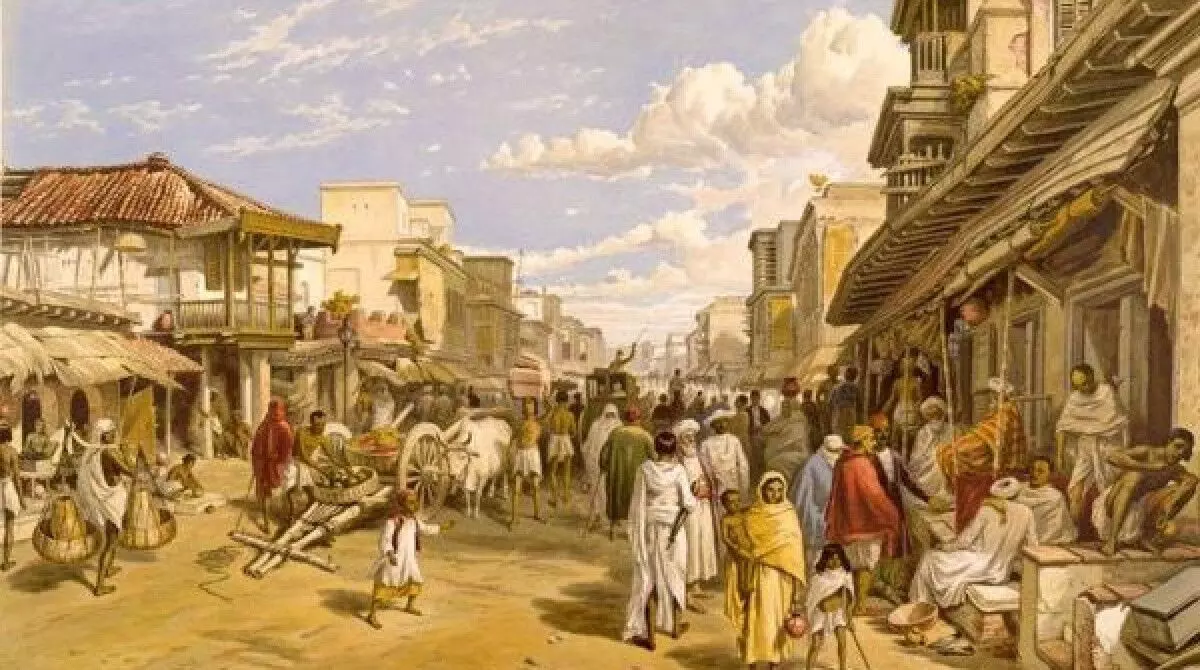

One of the most remarkable characteristics of India is her continuous and gradual development of multiple systems of governance channelised through various institutions. Somadeva Sūri of the 10th century in his ‘Nitivakyamrita’ rightly acknowledges the set of governance as a giver of 'dharma' and 'artha' by saying ‘atha dharmarthaphalaya rajyaya namah’. Such idealisation is the unique feat of achievement of Indic civilisation. The nature of the democratic institutions we have today is not a one-day event; rather it is a cultural journey of thousands of years. We have ample sources to understand the early Indian social institutions imbued with democratic elements of which references are scattered in Vedic literature, the Smritis, the Epics, the Purana literature, the Sutra literature, the drama, the poetry, the various folk tales. The tradition of democracy in one form or the other prevailed on this soil.

Various terms denoting this collective system were in vogue in early India right from the Vedic age. It is also true that different thinkers explained these terms differently which makes it difficult to ascertain their exact connotations. 'Samiti', 'sabha', 'kula', 'gana', 'jati', 'puga', 'vrata', 'sreni', 'samgha', 'samudaya', 'sambhuya-samutthana', 'charana' and 'parisat' were all designed to run the social as well as political life in early India. These terms are indicative of some sort of community living and the development of a system where policies and decisions were taken in complete harmony and consciousness.

The words 'samiti' and 'sabha' are frequently found in the Vedas, signifying ‘meeting together’ or more specifically an ‘assembly’ where political as well as non-political affairs were discussed in harmony. Sayana, the celebrated commentator of Vedas, reveals a very interesting fact about ‘sabha’ that its resolution which has been taken by many cannot be violated. The use of the word ‘sansad’ is found in the 'Atharvaveda'.

With the emergence of urban centres in the post-Vedic society, India saw a different set of self-governing systems where 'samiti' and 'sabha' paved the way for the emergence of other systems like 'gana', 'samgha' and 'sreni'. This Buddhist-Jain period saw the emergence of various 'ganas', the republican form of administration. In this phase, many institutions with democratic leanings have been established, and the concepts of 'gana' and 'samgha' have evolved. Jain texts conceive 'gana' as an assembly having a conscious mind for taking a decision. This indicates that 'gana' is a number and 'gana-rajya' means the rule of numbers.

Panini, the Sanskrit grammarian, in his magnum opus 'Astadhyayi', says that the word ‘samgha’ is in the sense of 'gana'. It appears that by the time of Panini (8th century BC), the word ‘samgha’ did not achieve any connection with religion and the meaning of this word was republic per se. Panini called them 'ayudhajivin' while Kautilya in the 3rd century BC categorised 'samgha' as 'sastropajivin' and 'rajasabdopajivin'.

Harmonising these two views, it becomes clear that there were 'samghas' who’s each member was observing the practice of military art and its ruler observed the practice of assuming the title of 'Rajan'. The ‘Majjhima Nikaya’ used 'gana' and 'samgha' simultaneously. We can take ‘gana’ as a form of government while ‘samgha’ as a body or state. The Mahabharata in its Santi Parva presents one of the most outstanding discussions on the nature and behavior of a ‘gana’ as a political community. The essence of the ‘gana’ lies in its confederacy or community living (‘samghata vritti’).

Thinkers like Panini, Kaiyata, Veda Vyasa, and Narada were all agreed to define the word ‘sreni’ as an assembly of persons following a common craft or trading in a common commodity – ‘eken silpena panyena va ye jivanti tesam samuhah srenih’. Sreni’ acts like an autonomous body. Their head or chief are known as ‘sresthin’. These guilds enjoyed a great reputation in society. ‘Sreni’ met regularly and discussed the policies of the local administration. These ‘srenis’ have the right to frame the rules for their own class and the king has to consult their representatives while making policy relating to them. The state by appointing ‘bhandagarika’ takes control over these ‘srenis’. It is interesting to note that various guilds not only established internal trade relations but also created a robust relation with ‘Tamraparni’ (Sri Lanka), ‘Suvarnabhumi’ (Sumatra) and ‘Baveru’ (Babylonia).

Early India witnessed considerable progress in the domain of arts, manufacturing and agriculture which inevitably led to formation of the ‘srenis’. All the Vedas, Brahmana texts, Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Pali literature are replete with references of the word ‘sresthin’, ‘sraisthya’, and ‘sreni’. The Ramayana presents a fascinating scene where a procession of citizen, which accompanied Bharata in quest of Rama, included gem-cutters, potters, weavers, armourers, ivory workers, well-known goldsmiths, merchants, washer-men, tailors, actors, actresses, physicians, wool manufacturers, perfume makers, and brahmanas of noble character. The Mahabharata also talked about the role and importance of these guilds in running the system. The famous Jetavana garden has been gifted to Buddha by a rich ‘sresthin’ named Anatha Pindika of Sravasti. The ‘Mahavamsa’, the historical chronicle of Ceylon, also mentions the heads of five trades who were assigned the duty of messenger to carry welcome from Kitti Srimegha to his son Parakrama. The ‘Harsacarita’ of Bana mentions the assemblage of skilled artists invited during the marriage ceremony of a princess. The ‘Harivamsa’ also records that the contest between Krishna and Balarama was witnessed by various royal families, citizens, and people belonging to different corporations.

Inscriptions like Sanchi, Bharhut, Bodhgaya, Mathura, Junnar and South Indian inscriptions record gifts donated by many prominent guilds of oil-millers, potters, makers of hydraulic engines, corn-dealers, bamboo-workers, weavers and many more.

The foundational spirit of ‘sreni’ and ‘samgha’ thus was intricately rooted in the deep sense of self-governance. The whole system was conceptualized to give an institutional outlook to the already developing congregations and cooperations. These social institutions followed a democratic set-up and possessed an early proto-type of community administration and social management.

When we take a deep dive in history and make an honest effort to assimilate facts, calling India the ‘Mother of Democracy’ does not appear to be an over statement.

The writer is Member Secretary of the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, New Delhi. Views expressed are personal