Not a panacea

The union government’s attempt to recruit joint and deputy secretaries through lateral entry holds little significance in curing the ills of governance

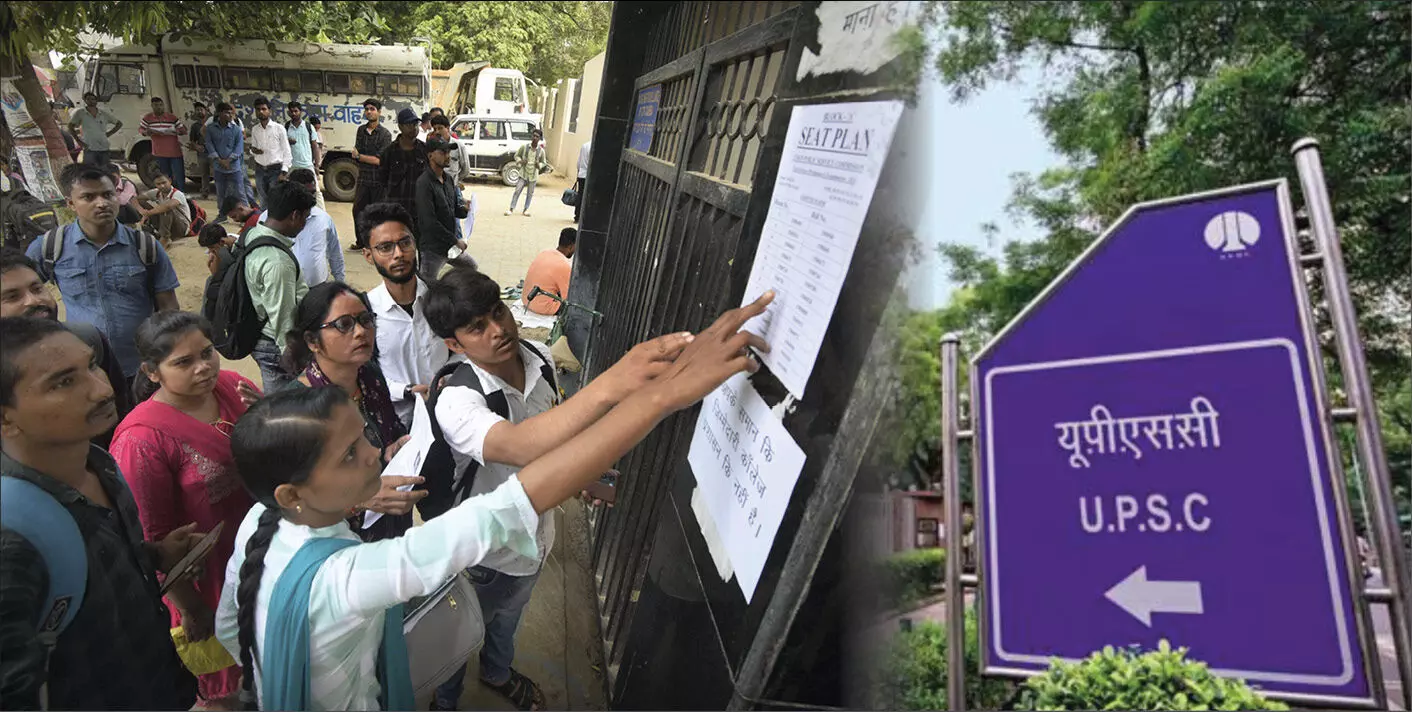

The issue of lateral entry has attracted a lot of discussion and controversy in the last few days, following the UPSC’s advertisement for recruiting specialists for 45 posts at Joint Secretary and Deputy Secretary/Director levels in the Government of India. The decision came under a strong attack from opposition parties, the government’s own allies, and Independent thinkers for not providing for reservation for these posts. Initially, the government defended its decision but subsequently cancelled the advertisement and professed its commitment to social justice. In all matters of direct recruitment to the Government of India, reservations must be provided. Lateral entry is a form of direct recruitment. If more and more people are recruited in this manner, then it would undermine the policy of reservation. I believe that the government has taken the right step by rolling back the advertisement.

Reservation is indeed a major issue, but this crucial intervention of lateral entry needs a thorough examination before the government ventures into it. The important question is about the rationale behind lateral entry. What problem in the current system of governance is lateral entry trying to solve? Proponents argue that lateral entry would infuse new blood and fresh ideas from outside the system, making it more rigorous and vibrant, ultimately leading to better results and higher performance. Their argument is that they are facing a disruptive technological environment that requires domain specialisation. It is felt that IAS officers or other civil service officers lack specialised knowledge, which is acting as a barrier to effective and forward-looking governance.

The problem, as identified by advocates of lateral entry, is that results are not coming at the desired pace, which is slowing down the nation's development. They feel that lateral entry is the panacea for all that is leading to less-than-optimal performance. However, the reality is that it is not the civil servants who are responsible for this situation due to a lack of domain knowledge; the problem lies with the bureaucratic structure and system of government functioning. The government's work is concerned with the proper utilisation of public money and requires uniformity of approach across the vast government system. This is the rationale for the labyrinthine web of processes, rules, and regulations that slow down decision-making. Civil servants are more concerned with following mandated procedures than delivering results because any violation could lead to a vigilance inquiry, and sometimes even criminal charges. The best civil servants, who are rated as dynamic and dashing at the beginning of their careers, often mellow down as the years go by, largely due to the pressure of the four Cs—CAG, CVC, CBI, and the courts. More often than not, an officer is looking over their shoulder and adopting a safety-first approach before making a decision. A civil servant learns the hard way that violating rules and regulations of any kind can land them in trouble, whereas not delivering results will not put them under scrutiny. A lateral entrant would face a similar situation, and I cannot fathom how a domain specialist would be able to navigate the system better than a civil servant.

It would be interesting to assess the nature of the work that a Joint Secretary or Deputy Secretary does. A large portion of their time is taken up by parliamentary matters. They prepare answers to parliamentary questions, anticipate likely supplementary questions, and brief the ministers. They prepare notes on issues concerning their department that are taken up for discussion in parliament and also attend meetings of parliamentary committees. In addition, they attend to legal cases, prepare agendas and minutes of meetings, draft notes on files, and draft letters. I do not see how a specialist would be able to handle this better than a civil servant whose career exposure has, in fact, made them a specialist in these matters.

More than domain specialisation, it is leadership qualities that are required. A civil servant at a senior level needs to be a leader who can coordinate with different departments and develop and motivate their team to get the job done. They need decision-making ability, and communication skills, and are required to develop systems of monitoring and evaluation. A civil servant, through their training, must have developed these qualities by the time they reach this level. If not, they can be trained to develop the same. There is no case for a domain specialist in this regard.

In any case, lateral entry at the Deputy Secretary level serves no purpose, as it is too junior a position for a specialist to make any significant contribution. They would just be pushing files without making any impact. There is a problem of officer shortages at the Deputy Secretary level, the reasons for which should be identified and addressed. Lateral entry is definitely not the answer. Enriching the role of the Deputy Secretary and providing certain creature comforts would certainly motivate more people to opt for Deputy Secretary level posts in the Government of India.

It is ironic that those who carry the banner for lateral entry of specialists also bemoan the silo approach in government and call for a cross-functional approach. A specialist is most likely to have a siloed viewpoint, whereas the multifunctional experience of an IAS officer is more amenable to thinking beyond silos in an integrated manner. In the words of Paul Appleby, an expert on public administration, it is the diversity of experience of an IAS officer that is most conducive to the formulation of good policies. Furthermore, to what extent should specialisation be pursued? A nephrologist and a paediatrician are typically so immersed in their area of specialisation that they would find it difficult to take a holistic approach to health policy, which an IAS officer is in a position to take. Besides, there is no substitute for the 8-10 years of experience working in districts, and understanding the problems and issues of marginalised sections of society, which provides a strong foundation for policymaking.

The civil servant is selected through an extremely tough and rigorous examination. In lateral entry, the proposal is to select people for the posts of Joint Secretary based on a 30-minute interview, which cannot match with over 20 years of experience working in the field as a civil servant.

I am not against having specialists in the government. In the words of Winston Churchill, the specialist should be "on tap" and not "on top." There is a strong case for having specialists as advisors to the ministry. Consultants can also play a role, but their use should be limited. Of course, outstanding individuals can be brought in to work for the government in their area of specialisation, like Nandan Nilekani chairing the Aadhaar project. They don’t need to come in as Joint or Deputy Secretary. Moreover, there are officers in the IAS with backgrounds in management, engineering, medicine, or economics. Their careers could be managed in a manner that allows them to bring the best of both worlds to their jobs. After about twenty years of service, IAS officers can be made to specialise in broad areas like finance, the social sector, energy, or infrastructure. Of course, they should then be posted in their areas of expertise and not get shifted around for political reasons.

Lateral entry into the government is an idea that needs serious rethinking. We must move away from the myths surrounding this concept to the realities of good governance. There are issues with the current state of governance, but these must be correctly diagnosed. The right remedy can only be prescribed if the root causes impacting effective governance are properly understood and analysed.

The writer is an ex-Chief Secretary, Govt of Uttar Pradesh. Views expressed are personal