Nehru’s Magnificent Obsessions

For India to course-correct historic foreign policy missteps, re-examining Nehru’s China obsession and 'Panchsheel' delusions becomes vital, especially when his echoes still haunt our borders and diplomacy

Some are trying to bury the spectres and ghosts of the past by saying “why discuss Nehru” now? Mostly those who have thrived on the Nehruvian system, argue on such a line and create a raucous whenever Nehru is discussed or invoked. It is an undeniable truth that Nehru’s blunders were of gigantic proportions. For decades these problems were allowed to fester by Nehru’s political heirs and today, when there is an attempt to course correct those wrongs by the Narendra Modi dispensation, the dissolving Nehruvian system surprisingly howls in pain. Why is it unnecessary to discuss the political blunders and debilitating stances and decisions taken in the early decades after independence? Why should not these be in regular public discourse?

A continued and informed discussion on these, is imperative for the growth, in each generation, of an effective understanding of India’s national security challenges and of how decisions made then had long term and complex implications. In any serious parliamentary debate or discussion, the drawing of long links is important for such debates to be effective and useful. While speaking during the Operation Sindoor debate in Parliament, both PM Modi and HM Amith Shah were doing just that. They were drawing the links and lines in order to establish the present-day security challenges of how for decades the Congress system ignored these challenges, addressed them piecemeal and or simply capitulated before them.

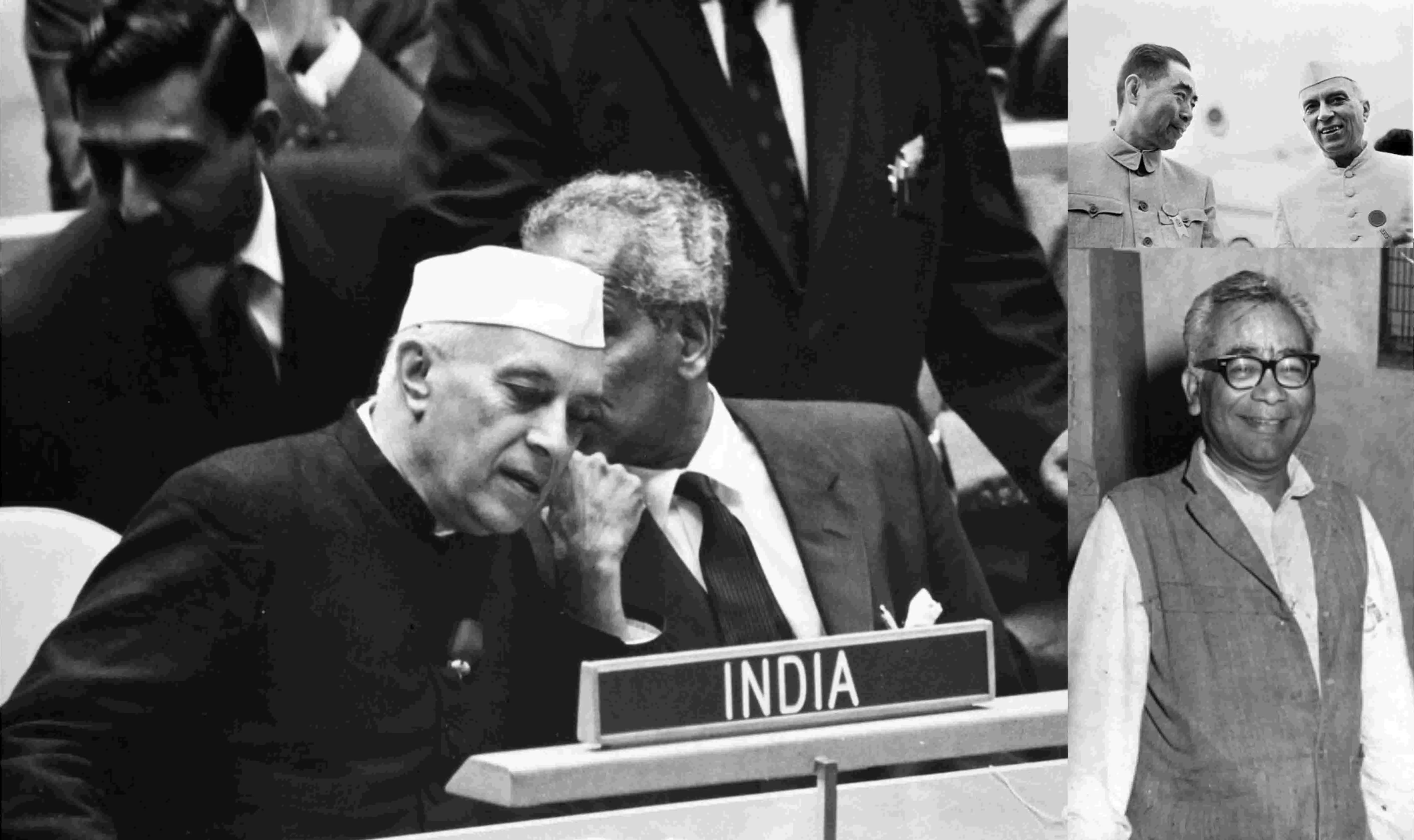

Pandit Nehru’s blunders with China, his false sense and pretenses, need to be mentioned in that context. Let us look at his obsession with seating China in the United Nations without a regard for India or for India’s strategic and foreign policy interests.

Let us start with Nehru’s hollow Panchsheel which in 1954 gave rise to a false sense of complacency, allowing China to chip away Indian territory. In their epic analysis of Nehru’s tenure as Prime Minister, authors Amiya and BG Rao wrote that Nehru had told the “country in 1954 that Panchsheel was a guarantee against aggression, against China crossing our frontier. But he had not told the people that crossing an unrecognised frontier was no aggression; and since that China had never recognised the frontier as in our maps; Panchsheel could not be invoked.” Towards the end of September 1959, the AICC just passed a resolution expressing “great regret that Panchsheel should have been ignored and by-passed by the Chinese Government.”

A weak and rudderless Panchsheel was upheld by Nehru’s determination to seat China at the UN. In his letters to the Chief Ministers on January 23/24 1958, Nehru wrote, referring to the “Gauhati Session of Congress, 16-19 January”, that the Session “had supported the government’s policy of non-alignment and its stand on inclusion of People’s [Republic of] China in the United Nations…”

Speaking in Hyderabad in October 1959, Dr Rammanohar Lohia, made a caustic assessment of Pandit Nehru’s foreign policy since independence. Lohia hit hard when he said that, “nothing concrete has been achieved in the last ten or twelve years in the field of foreign policy,” saying that it was “the history of mere words, attractive words. And the people were caught in the net of words.” But the situation was now changing, “and the people are able to grasp the situation. Whether it is the Goa problem or Kashmir or the question of northern borders, the policy has turned into a fiasco everywhere.” Lohia referred to Nehru’s Panchsheel formula as a “hollow phrase” whose “utterance gives a sentimental satisfaction to the people and the government.”

The Bharatiya Jana Sangh, with Deendayal Upadhyaya as its driving force, in its all-India session in Nagpur in January 1960, spoke of having warned the government against the “aggressive designs of communist China” as early as December 1953 and referred to the Nehru government’s “masterly inactivity first in respect of China’s cartographic invasion of India’s frontiers and then even regard to their actual violation.” It accused the Nehru government of “calculatedly keeping the people and the Parliament entirely in the dark in respect of China’s misdeeds on the one hand and, on the other, allowing the people to be lulled into a false sense of security by chanting Panchsheel Mantram in chorus with China.”

In September 1961, the Socialist Party’s national committee resolution, in its meet in Ayodhya, in September 1961, expressed its “disgust at the continued support of the India Government to China’s admission into the United Nations.” It argued that while the “India Government has refused to establish diplomatic relations with Israel on the plea that she invaded Egypt, although without having been able to occupy any territory…It is so wanting in national pride and international morality as not to attach any importance to the invasion of India by China and the occupation of Indian territory and thus establish for all time its anti-national character.”

Between 1959 and 1962, while China gobbled up and violated Indian territory, Nehru persisted with supporting China’s right to be in the UN. It was, write Amiya and BG Rao, “almost an article of faith with Nehru that if Peking was found a seat in the Council, she would be more amenable to a peaceful solution of all problems, in particular the problem of the Sino-Indian frontier.”

Whether it was naivety or an “I know it all” symptom that drove Nehru, is difficult to say. But he was obsessed with trying to seat communist China in the UN despite its openly hostile and expansionist approach vis-à-vis India. He clung to his obsession even in the last week of October 1962, and “voted for seating Peking” in the UN though, Australia opposed by arguing that “the moment, when headlines were full of the latest evidence of Peking’s attitude to the use of force, is hardly the time for the Assembly to give a mark of approval to these aggressive courses.”

On October 27, 1962, in a press statement in Delhi, Lohia ruefully remarked, “on the news that India supported China’s admission to the United Nations at the general assembly.” It is, Lohia said, “a most shameless thing to do, not alone from India’s viewpoint but from that of world freedom and peace. If the principle of universality prompts China’s admission, what of Taiwan’s (Formosa’s)” he asked.

On 8 November 1962, while China had made inroads and invaded India, when, in his own words, India was “facing a regular and massive invasion of our territory by very large forces”, Nehru told Lok Sabha on why he persisted with his magnificent obsession of trying to seat communist China at the UN.

In his inimitable style, he told the House, that “we have supported it [Chinese representation in the United Nations] in spite of this present invasion, because we have to look at it this way: it is not a question of likes or dislikes It is a question, which will facilitate Chinese aggression; which will facilitate its misbehaviour in the future. You might disarm the whole world and leave China, a great, powerful country, fully armed to the teeth. It is inconceivable. Therefore, in spite of our great resentment at what they have done, the great irritation and anger, still I am glad to say that we kept some perspective about things and supported that even now.”

All these hollow words, grandstanding and confused utterances in favour of China’s right of entry at the UN came after China had battered us, grabbed our territory, insulted and assaulted us. Only Nehru could discern and analyse Nehru’s words, or its meaning and the level of unabashed shamelessness that they displayed.

In the late 1950s, Acharya Devaprasad Ghosh, then president of the Jana Sangh, a Rajya Sabha member between 1952-54, once observed that, “Neither Goa nor Kashmir is a problem of India, Pandit Nehru is the problem number one of India.” In India’s march to emerge as a great power today, Nehru’s heirs and their minions continue to be the “problem number one for India.”

The writer is a member of the National Executive Committee (NEC), BJP, and the Chairman of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal