Nationalism as a Moral Crusade

As force dominates global politics again, Gandhi’s ethical nationalism offers a conscience-driven alternative to violence, coercion and exclusion

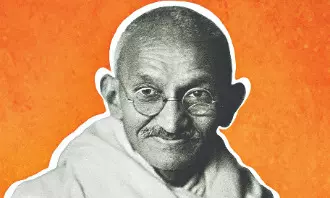

January 30 is a date etched into the global consciousness not merely as the anniversary of a political assassination, but as the moment a mortal man crossed into the realm of an enduring moral conscience. Seventy-eight years ago, the three bullets that silenced Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi paradoxically amplified his voice, allowing it to echo across decades and continents, into a 21st century marked by wars, polarisation, and profound technological estrangement. As we commemorate his 78th martyrdom, remembrance must move beyond hollow hagiography—beyond statues, slogans, and postage stamps. To truly remember Gandhi is to engage seriously with his most radical experiment: the belief that truth and love could be wielded as political forces, and that politics itself must ultimately be a branch of ethics.

Gandhi described Satyagraha as “soul-force pure and simple”—a weapon of the strong, not the weak. It was an appeal to the conscience that sought to confront injustice without replicating its violence. Rooted in what he called suffering love, Satyagraha was, in essence, a “surgery of the soul,” aimed at expanding human moral capacity rather than humiliating or destroying the opponent. The political theorist Bhikhu Parekh explains Gandhi’s method by noting that he assumed the burden of common evil, sought to liberate both himself and his adversary from its tyrannical logic, and thereby reduced the prevailing level of inhumanity. Gandhi’s struggle, therefore, was never simply against the British Empire, but against the moral corrosion that empire produced in both ruler and ruled.

This ethical framing shaped Gandhi’s position even at the most fraught moments of India’s history. During the Partition negotiations, he challenged the very language of the two-nation theory, arguing that such a conception of nationalism was absurd for a civilisation as diverse as India’s. Unity, for Gandhi, was not merely a political necessity but a moral imperative. His refusal to surrender to the logic of religious nationalism cost him popularity, political leverage, and ultimately his life. Yet it is precisely this moral defiance that gave his nationalism global resonance. Leaders across continents recognised in Gandhi not just a freedom fighter, but a thinker who had redefined the very purpose of political struggle.

In today’s deeply polarised world—fractured by war, extremism, and ideological absolutism—Gandhi’s concept of soul-force offers an alternative path. Martin Luther King Jr., reflecting on Gandhi’s legacy, described Satyagraha as “truth-force” or “love-force,” capable of disarming oppressors through disciplined nonviolent resistance. King’s application of Gandhian principles during the American civil rights movement stands as proof that Gandhi’s methods were not culturally specific but universally adaptable. Gandhi himself, days before his death, expressed doubt and humility, wondering aloud whether he possessed the nonviolence of the truly brave, and whether only his death would answer that question. King later observed that while Christ provided the spirit, Gandhi provided the method.

For Gandhi, nonviolence was never passive. It was an active, dynamic force rooted in moral courage and inner discipline—what he called ahimsa in its highest form. “Nonviolence is the greatest force at the disposal of mankind,” he famously said, elevating it beyond the mere absence of violence into a transformative principle. At a time when global crises—from geopolitical brinkmanship to social fragmentation—test the limits of human solidarity, Gandhi’s insistence on conscience over coercion speaks with renewed urgency. His conviction that nonviolence is the weapon of the strongest challenges contemporary societies to reconsider their definitions of power, success, and justice.

The Canadian philosopher James Tully, reflecting on Gandhi’s influence on civic freedom, emphasised that nonviolence transforms the relationship between opponents by disrupting cycles of retaliation. Instead of victory and defeat, Gandhi envisioned politics as a space for moral persuasion and mutual transformation. This reorientation—from domination to cooperation—makes Gandhi’s philosophy not a relic of the past but a living political resource. It also explains why Gandhi elevated Indian nationalism from a movement of political agitation into a moral crusade with universal appeal.

As historian B.R. Nanda observed, Gandhi’s nationalism was inclusive rather than exclusive—a nationalism that served as a stepping stone to internationalism. By tying the freedom struggle to the upliftment of the “last man” (Antyodaya) and the eradication of untouchability, Gandhi ensured that independence was not severed from social justice. Freedom, for him, was hollow if it did not transform the lives of the most marginalised. Nationalism divorced from ethics, he warned, would simply replace foreign domination with indigenous injustice.

Ashis Nandy has argued that Gandhi’s greatest contribution lay in offering a critique of modern Western civilisation from within its own traditions of dissent. Gandhi did not merely demand inclusion within the imperial order; he sought to fundamentally challenge its assumptions about progress, power, and violence. Through Satyagraha, he forced the British Empire to confront the moral contradictions embedded in its own claims of democracy and fair play. The struggle for Indian independence thus became a mirror in which imperial hypocrisy was exposed.

German-American psychoanalyst Erik Erikson, in Gandhi’s Truth, described how Gandhi transformed personal vulnerability into revolutionary strength. Gandhi’s moral calculus, Erikson noted, allowed him to confront failure not with denial but with resolve, often framing it through vows of “never again.” This capacity for self-critique made Gandhi both human and formidable, grounding his politics in ethical introspection rather than ideological rigidity.

To understand Gandhi’s moral force is to recognise how profoundly he reimagined nationalism itself. Traditionally, the nation was understood as a territorial or political unit. Gandhi insisted that nationalism without ethical foundations—without service to truth and human dignity—was empty. “Indian nationalism is not exclusive, nor aggressive, nor destructive,” he wrote. For him, swaraj (self-rule) was inseparable from the swaraj of the self. Liberation meant freedom not only from colonial rule but from hatred, prejudice, and moral indiscipline. In Hind Swaraj (1909), he rejected dominant Western models of civilisation and proposed instead a vision of self-government rooted in restraint, responsibility, and ethical living.

Today, as the doctrine of “might is right” resurfaces with alarming confidence—from physical battlefields to digital spaces—Gandhi’s philosophy appears less idealistic and more necessary. The Austrian philosopher Martin Buber, though occasionally critical of Gandhi’s applications, recognised his singular achievement in bringing ethical spirit into everyday political life. In an age of misinformation and “alternative facts,” Gandhi’s insistence on Satya—truth as an objective moral pursuit—serves as an essential anchor.

As Faisal Devji argues in The Impossible Indian, Gandhi’s power lay in his refusal to become a static icon. His life was an argument, not a consensus. Ritualised remembrance—though important—risks neutralising the discomfort Gandhi sought to provoke. To honour him, Devji suggests, is to continue the argument he began. Remembering Gandhi, therefore, demands more than reverence. It requires engagement with the difficulty of his ideas and the discipline of his practice.

In an age of artificial intelligence, technological acceleration, and geopolitical brinkmanship, does Gandhi still matter? The answer lies in the enduring relevance of his “Seven Social Sins,” particularly politics without principles and science without humanity. Gandhi’s soul-force remains perhaps the only antidote to a world growing increasingly soulless. It reminds us that the means are inseparable from the ends—and that in the final reckoning, how we act matters as much as what we achieve.

Views expressed are personal. The writer is Programme Executive, Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti