Leadership of Moral Stability

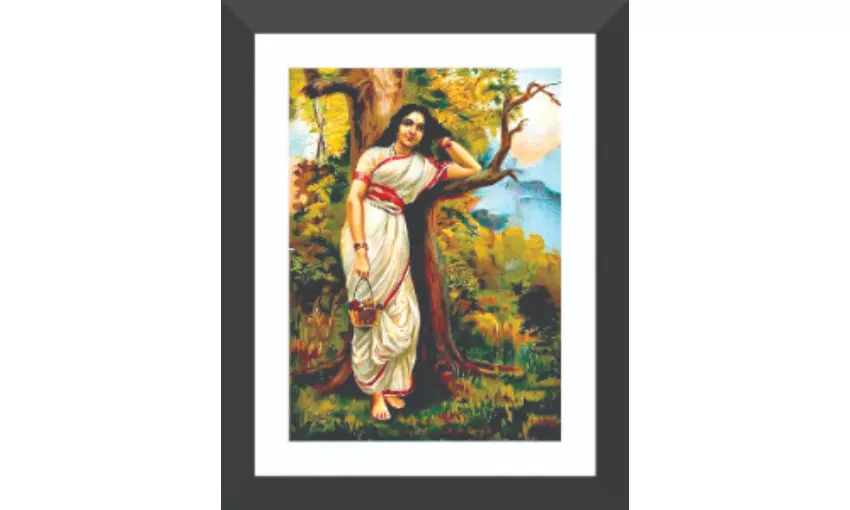

Ahalya’s story from the Ramayana becomes a modern leadership parable on power asymmetry, accountability, restraint and the ethics of institutional renewal

“A ruler grounded in dharma and committed to truth stands firmly established in the world”

– Valmiki Ramayana, Ayodhya Kanda

Leadership lessons are often associated with tales of kings who ruled empires, warriors who won battles, or reformers who redefined institutions. Yet some of the most enduring insights into leadership emerge not from figures of authority, but from individuals within organisational systems who bear the consequences of their actions. The story of Ahalya, as related in the Ramayana, illustrates this quieter moral terrain.

Traditionally remembered through the narrow perspective of transgression and redemption, Ahalya’s narrative offers a refined lens on power asymmetry, institutional response, leadership responsibility, and the ethics of renewal. In an age of constant scrutiny and accountability expected by stakeholders and public perceptions, Ahalya’s story provides a framework for contemporary leadership that is both unconventional and necessary. This is not a tale of personal morality alone, but a study of how leadership ecosystems respond to ethical breaches while sustaining institutional continuity.

Ahalya, created by Brahma himself, was married to Sage Gautama and was known for her intellect, integrity, and moral standing. They lived in an austere hermitage, removed from the intrigues of kingdoms but not from hierarchies of influence. Indra, king of the devas, deceives her by assuming Gautama’s identity and breaches trust under false pretence. When Gautama discovers the violation, he curses Ahalya into invisibility and suspension. The severity and immediacy of his response also reveal a familiar leadership vulnerability. When confronted with betrayal, reputational damage, or emotional distress, even principled leaders take hasty action without the benefit of full reflection. Decisions taken in such moments are often erroneous and disproportionate, and while authority may justify the action, time can later reveal the response to have been harsher than the long-term interests of justice or institutional balance required.

In this instance, Ahalya is neither eliminated nor included, existing in a state of professional and moral exclusion until Lord Ram later restores her dignity and position in the family and society. Indra’s punishment, by contrast, is temporary and does not permanently displace him from authority. The unevenness of these outcomes reflects a common organisational reality, where responsibility, rank, and consequence are not always matched across levels of power.

Yet the story does not end in permanent rupture. Ahalya’s transformation represents exclusion from participation rather than annihilation. She becomes silent, unseen, and removed from participation. In corporate terms, this resembles reputational or professional marginalisation rather than erasure. The deeper leadership lesson lies not in the event itself, but in how she responds upon restoration. She does not engage in narratives to defend, negotiate or justify her actions. Her stillness reflects ethical composure. This reinforces a central leadership principle that individuals cannot be permanently defined by a single episode, but must be evaluated through their capacity to endure consequences with composure. This demonstrates the critical leadership capability of accepting accountability without attempting to control perception. In organisational life, error often triggers defensive communication, positioning, or symbolic gestures designed to protect image. The focus shifts to narrative management rather than ethical restoration. Ahalya’s response is different. By not interfering with the corrective process, she allows institutional mechanisms of judgment and renewal to function. Leadership credibility, therefore, is sometimes preserved not through justifications but through restraint and trust in process. This also affirms that time, reflection, and space for course correction are essential to healthy organisational cultures.

Her silence carries additional leadership meaning. Silence here is not disengagement, but disciplined reflection. In modern enterprises, leaders are often expected to respond instantly. Yet a premature response can escalate risk. Ahalya’s restraint highlights the importance of pause, assessment, and considered action. It also cautions organisations against radical, irreversible steps taken in moments of emotional intensity. Effective leadership frameworks must allow room for error, learning, and proportional correction rather than permanent exclusion.

When Lord Ram restores Ahalya, the act is quiet and dignified. There is no public spectacle, no humiliation, and no symbolic grandstanding. Ahalya resumes her place without demanding recognition. This reflects a corporate leadership ideal where restoration of dignity follows inner transformation, not public display. Ram’s role here models system-level leadership. A great leader does not assert authority by amplifying error or humiliating individuals. Instead, he strengthens the system quietly, corrects the imbalance without spectacle, and restores people without diluting standards. Forgiveness, in this sense, does not weaken accountability. It reinforces it by demonstrating that institutions are capable of correction without erosion of principle.

Ahalya’s conduct also demonstrates proportionality. She neither magnifies nor diminishes her experience. In organisational settings, disproportionate response to failure can damage morale and trust. Justice must be contextual and measured. Leaders who overemphasise personal hardship risk shifting attention away from institutional interests, while those who ignore it risk emotional disengagement. A culture of trust requires a balance between empathy and accountability.

Her refusal to convert suffering into entitlement offers another corporate leadership lesson. Personal adversity does not automatically confer authority or moral exemption. Ahalya does not leverage her ordeal as a claim to authority, exemption, or sympathy. Leadership cultures deteriorate when grievance becomes currency. Ahalya’s restraint preserves fairness and reinforces merit over narrative.

Her experience with moral asymmetry also mirrors organisational realities where influence and hierarchy affect outcomes. In this episode, she finds herself in a framework where power was unevenly distributed and proved to be detrimental to her interests. She navigates this without rebellion or withdrawal, demonstrating that ethical steadiness remains possible even in imperfect systems. This steadiness strengthens institutional culture over time and reinforces confidence among the stakeholders.

Indra’s conduct represents a separate leadership risk. Power detached from ethics leads to systemic distortion. After Gautama discovers the deception, he immediately sheds his disguise and acknowledges his wrongdoing. In the Valmiki Ramayana, this acceptance represents his repentance. When influential individuals evade proportional accountability, institutions are obliged to absorb the damage. Long-term leadership credibility requires alignment between authority and responsibility.

Another leadership lesson lies in Ahalya’s comfort with complexity. Her story resists simple binaries. She is neither fully innocent nor irreversibly guilty. By holding this ambiguity without defensiveness or denial, she reflects a style of leadership suited to present complex and uncertain environments. This acceptance provides space for accountability without forcing either total self-absolution or permanent condemnation. In contemporary institutions, leaders who demand absolute innocence or total blame tend to inhibit reflection and learning. Ahalya’s ability to accept complexity, on the other hand, enables correction, making her narrative especially relevant to modern organisational ethics.

Her restoration also reframes the nature of forgiveness. Lord Ram does not absolve publicly or stand in judgment of Gautama’s decision, but recognises the need for correction. Forgiveness here is not transactional. Ahalya also does not demand forgiveness, nor does she repent to earn it. This suggests that leadership cultures should distinguish between demonstrative forgiveness and forgiveness as a recognition of transformation. Institutions that forgive demonstratively defeat their purpose, but those that forgive discerningly strengthen moral continuity.

Gautama’s response to Ahalya’s restoration is marked by restraint rather than defensiveness, and it carries an important leadership lesson. When Rama’s presence lifts the curse, Gautama does not contest the reversal or cling to the finality of his earlier judgment. Instead, he accepts the restoration as just, implicitly acknowledging that the punishment had served its purpose and that correction was now warranted. He welcomes Ahalya back, resumes their household life, and restores her dignity without qualification. This willingness to accept course correction, especially when initiated by a higher moral authority, reflects mature leadership. It shows that authority is not diminished by revising past decisions but is strengthened when leaders recognise that justice has been served and renewal is necessary. Gautama’s acceptance models an ethic of leadership where firmness is balanced by humility, and where restoring trust is valued as highly as enforcing order.

Ahalya’s reintegration into life also demonstrates yet another subtle leadership value. Humility without self-abasement. She does not withdraw into obscurity after restoration, nor does she seek prominence. She resumes her place in society with modesty and composure. This humility is instructive in leadership transitions where individuals must return to responsibility after periods of absence or failure. Effective reintegration requires modesty that does not erode competence and confidence that does not assert entitlement. Ahalya embodies this equilibrium.

For modern organisations, navigating the demands of reform, accountability, and social trust, Ahalya offers a leadership ethic of rare relevance. She does not hold power or define strategy. Yet her journey reveals leadership as the capacity to endure consequence without losing identity, to accept correction without entitlement, and to preserve institutional harmony over personal narrative. In an era that rewards immediacy, her example reminds organisations that sustainable leadership cultures are built on balance, empathy, accountability, and the belief that learning and redemption are integral to long-term success for any organisation.

Views expressed are personal. The writer is Chairperson Bharat Ki Soch