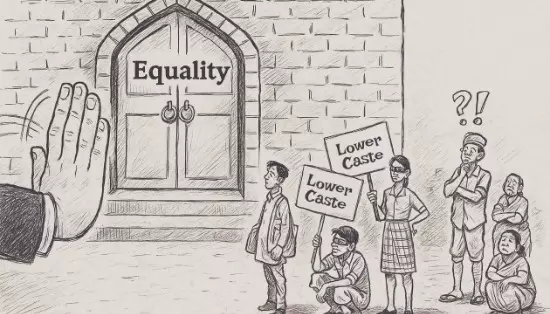

India’s Silent Crisis

Despite laws and progress, caste discrimination continues to poison India’s social fabric, revealing the limits of reform without empathy

As an observer of human behaviour, I am deeply affected by the persistent social divides in India, particularly caste discrimination. Despite my position, I feel powerless to change the deeply ingrained mindsets and social behaviours that perpetuate inequality. Education is often heralded as a beacon of enlightenment, revealing our shortcomings and fostering progress. Yet, for many, this promise remains unfulfilled. The caste system, with its millennia-old roots, continues to cast a long shadow over Indian society, dividing communities and denying millions the dignity they deserve. While laws, reforms, and success stories of the marginalised offer hope, caste discrimination remains a stubborn reality, manifesting in overt and subtle forms across rural and urban landscapes.

Roots of the Caste System

The caste system, encompassing varna (broad social classes) and jati (birth-based sub-castes), is deeply entrenched in South Asia’s history, codified in ancient texts like the Vedas, Manusmriti, and other dharma-shastra works. These texts divided society into four hierarchical varnas: Brahmins (priests and teachers), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (merchants and farmers), and Shudras (servants and labourers). Beyond these categories were the “untouchables,” later termed Dalits, who faced extreme social exclusion and were relegated to menial, stigmatised tasks. Over centuries, jati evolved into thousands of sub-castes, dictating occupation, marriage, social interactions, and ritual status. This rigid structure fostered a culture of hierarchy and exclusion, embedding discrimination into the fabric of daily life.

Legal and Constitutional Safeguards

India’s Constitution, enacted in 1950, sought to dismantle caste-based inequities. Article 17 abolished “untouchability,” while other provisions guaranteed equality before the law, prohibited discrimination based on caste, and introduced affirmative action for marginalised groups. Key legislative measures include:

* Protection of Civil Rights Act (1955): This law prohibits practices of untouchability, aiming to ensure equal access to public spaces and resources.

* Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989: This act criminalises specific offences against Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), offering stronger protections against violence and discrimination.

* Reservation Policy: Reservations in education, public employment, and legislatures aim to uplift SCs, STs, and Other Backwards Classes (OBCs), fostering representation and social mobility.

Despite these measures, enforcement remains inconsistent. Victims of caste-based discrimination often face delays in justice, a lack of evidence, social pressures, and power imbalances. In some cases, local authorities’ complicity undermines the law’s effectiveness, leaving marginalised communities vulnerable.

Persistent Forms of Discrimination

While overt practices like physical segregation—separate hamlets, wells, or temple restrictions—persist in rural areas, caste discrimination has also taken subtler forms in modern India. Social customs, implicit biases, and institutional practices continue to marginalise Dalits, STs, and OBCs. For instance:

* Violence and Atrocities: Though less frequent than in past decades, caste-based violence persists. The 2012 Laxmipeta massacre in Andhra Pradesh, where dominant caste groups brutally attacked Dalits, exemplifies this ongoing brutality. Such incidents spark outrage but often fail to lead to systemic change.

* Social Exclusion: Practices like denying access to public spaces, requiring separate utensils, or enforcing “untouchability” in villages remain prevalent. Human Rights Watch’s “Hidden Apartheid” report documents these persistent practices affecting millions.

* Economic Disparities: Marginalised castes face systemic disadvantages in labour markets, land ownership, and livelihoods. They are overrepresented in low-paid, informal, and hazardous jobs, with limited access to assets, credit, or formal employment.

* Education and Social Stigma: While school enrollment among Dalits has improved, high dropout rates, teacher prejudice, and casteist bullying persist. Students often face exclusion or derogatory remarks, hindering their educational progress.

Institutional and Subtle Discrimination

Even in urban settings and elite institutions, caste discrimination remains a lived reality. The tragic case of Rohith Vemula, a Dalit PhD student at the University of Hyderabad, whose 2016 suicide sparked nationwide protests, exposed caste-based harassment in academia. Similarly, the 2023 suicide of IPS officer Y Puran Kumar in Haryana highlighted caste-based discrimination within the police and administrative systems. Kumar’s final note reportedly cited years of harassment due to his Scheduled Caste identity, a claim echoed by his wife, a senior administrative officer, and supported by demands to include caste-based discrimination in the FIR.

These high-profile cases are merely the tip of the iceberg. Millions of similar stories go unreported, buried under social stigma and fear of retaliation. As someone from a small town in Haryana, I have witnessed caste discrimination firsthand— from a roti handed at arm’s length to a Dalit sanitation worker, to disdain in schools, colleges, and universities. Even in the “enlightened” realm of higher education, where I have served, caste-based cliques and bullying create toxic environments, demotivating and marginalising those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Challenges in Eradicating Caste Discrimination

Despite legal frameworks, caste discrimination persists due to several factors:

* Weak Enforcement: The SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act and other laws are often undermined by delays in the judicial process, lack of evidence, and victims’ fear of retaliation or ostracism. Caste-based slurs are frequently dismissed as trivial, further discouraging reporting.

* Deep-Rooted Social Beliefs: Centuries-old traditions and biases perpetuate caste hierarchies. Many believe discrimination is a rural or outdated issue, yet for marginalised communities, it remains a daily reality, often disguised in subtle attitudes or exclusionary behaviours.

* Economic and Structural Inequities: Marginalised castes often face poverty, limited access to land, credit, healthcare, and sanitation, compounding the effects of social discrimination. These structural disadvantages reinforce caste-based exclusion.

* Political Manipulation: Caste is often exploited in politics, with caste-based rallies and census demands fueling both empowerment and division. Dominant castes, in some cases, resist relinquishing their privileges, perpetuating inequalities.

The Path Forward

Eradicating caste discrimination requires a multi-pronged approach combining systemic reforms and societal transformation:

* Strengthening Legal Enforcement: Swift, sensitive, and fair implementation of the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act is critical. Training police, judiciary, and administrative officials to handle caste-related issues with empathy and efficiency can enhance accountability.

* Addressing Structural Inequities: Beyond reservations, targeted programs in land reform, credit access, employment, housing, and healthcare can address systemic disadvantages faced by marginalised communities.

* Social Awareness and Education: Schools and universities must foster inclusive environments, addressing casteist attitudes through curricula and sensitisation programs. Media, NGOs, and social movements play a vital role in amplifying marginalised voices and pressuring governments for action.

* Challenging Mindsets: Deeply ingrained biases require sustained efforts to change. Community dialogues, inter-caste initiatives, and public campaigns can promote empathy and dismantle stereotypes.

Call for Collective Action

Caste discrimination is not a relic of the past; it is a living challenge that demands urgent attention. Legal and constitutional safeguards have made strides, but social change lags behind. For a truly inclusive society, India must confront discrimination head-on, ensuring accountability, empowering marginalised communities, and fostering a culture of equality. As Walt Whitman poignantly wrote in I Sit and Look Out:

I sit and look out upon all the sorrows of the world, and upon all oppression and shame… I observe the slights and degradations cast by arrogant persons upon labourers, the poor, and upon negroes, and the like; All these—All the meanness and agony without end, I sitting, look out upon, see, hear, and am silent.

Unlike Whitman’s silent observer, we cannot afford to remain passive. The resilience of those who endure caste discrimination—the “lesser mortals” with a “never say die” spirit—inspires us to act. By recognising discrimination, ensuring justice, and fostering societal change, we can bridge the divide that has fractured India for too long. The time for an inclusive, equitable society is now.

Views expressed are personal. The writer is the Vice-Chancellor of SGT University, Gurugram