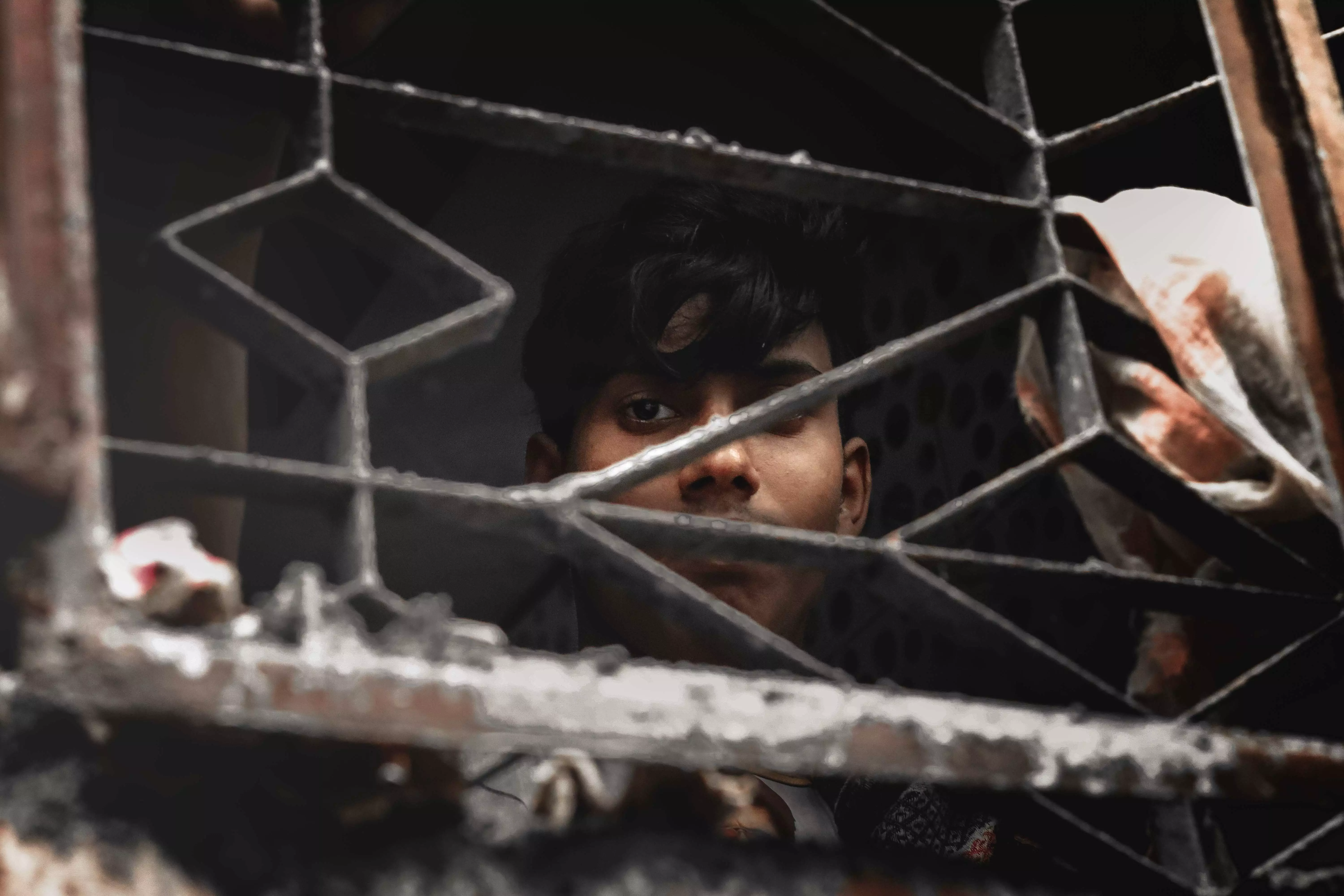

Childhood in chains

The institutionalised and exploitative nature of child servitude in the Indian subcontinent has been leading to suppression of the most basic human rights of children

Forced or bonded child labor is considered to be the most exploitative and egregious form of servitude. Historically, it has been known as child slavery. There are millions of children whose labor can be considered forced. These include child bonded laborers – children whose labor is pledged by parents as payment or collateral on a debt – as well as children who are kidnapped or lured away in various ways from their families and imprisoned in sweatshops or brothels.

Millions of children around the world work in various domestic services. Although no reliable global or national figures exist on the number of children engaged in forced domestic employment, the figure is in the tens of millions worldwide, and is on the increase.

The South Asian Coalition on Child Servitude estimates that there are approximately ten million child laborers in “chronic bondage” in India alone. The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that the number of enslaved children is increasing in some sectors and industries despite national and international laws prohibiting the practice.

Forced child labor is found primarily in informal, unregulated or illegal sectors of the economy. As the London-based human rights organization Anti-Slavery International (ASI) states:

It is an axiom that the weakest and most marginalised groups of people are the most vulnerable to exploitation. Within the context of slavery, indigenous people along with women and children are amongst the groups most affected.

The report goes on to say that forced child laborers work in conditions “that have no resemblance to a free employment relationship.” They receive little or no pay and have no control over their daily lives. They are forced to work beyond their physical capacity and under conditions that seriously threaten their health, safety and development. Even in cases where they are not physically confined to their workplace, their situation may be so emotionally traumatizing and isolated that, once drawn into forced labor, they are unable to conceive of a way to escape. There are no specific international standards on forced child labor. Forced labor is defined by ILO Convention 29 on Forced or Compulsory Labor as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.”

The United Nations 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery defines slavery to include: debt bondage, serfdom and any practice whereby a person under 18 years of age is delivered by his parent/guardian, whether for reward or not, with a view to the exploitation of the young person or his labor.

In 1994, the United States imported USD 156 million of hand-made carpets from India. It imported USD 48 million worth of hand-made carpets from Pakistan and USD 5 million worth of hand-made carpets from Nepal in the same year. Statistics show that the US is one of the largest buyers of goods produced by children in this Third World country. It’s ironic that one of the major advocates of children’s rights is enjoying luxuries that are a product of child slavery.

Perhaps in no other industry is the problem more evident than in carpet weaving. In April 1994, the South Asian Coalition on Child Servitude (SACCS) estimated that there is a total of one million children in servitude engaged in the carpet industry in the Indian Subcontinent – 500,000 in Pakistan, 300,000 in India and 200,000 in Nepal. There is evidence, however, which is discussed here later, that there has been a significant reduction in the number of children in the industry in Nepal since early 1994. The Indian carpet industry is widely dispersed over a large geographical area.

Bonded children in the carpet industry are often recruited from the neighboring states of Bihar and Madhya Pradesh by both agents and organized gangs. Their parents, low-caste, poor peasants or landless laborers, are given a cash advance ranging from 1,400 to 6,300 rupees (approximately USD 20 to USD 90). Those children whose parents take advances are required to continue working for the same employer until the advance has been repaid. The amount of time it takes to repay the loan can extend up to five or six years.

The worst condition occurs in production units that rely on migrant child laborers. SACCS estimates that over 70 per cent of the children working in the carpet industry are migrant children from neighboring states, the majority of whom receive no wages. The majority of migrant child carpet weavers are not given an opportunity to visit their homes for long periods of time after they begin working in the carpet industry. One report states that “It is not uncommon for these children to leave their villages never to be heard from again.”

Once the children arrive at the loom shed, any advance paid to their parents is deducted from the children’s already low wages. The cost of meals, usually inadequate and of poor quality, is deducted from their pay. Some children are paid only in food, including young children who are deemed apprentices for a period that can last from one to five years.

Bonded carpet children work up to twenty hours per day, seven days a week, and often sleep, eat and work in the same small, damp rooms. When there is a rush order, the workers may be required to work without sleep. Those who try to escape are often beaten, deprived of food or tortured. Cases have been documented where children trying to escape were hanged or shot to death, chained to looms, or branded with irons. Girl carpet workers are sexually abused.

In Pakistan, bondage begins at home when the head of a weaver household accepts advances from a thekadar (contractor). The middleman controls the looms, provides material, and transports finished carpets to export centers. Payment is made to the family weavers according to the quantity and quality of work produced, but the families rarely receive enough income to cover payments on the initial loans.

Often the parents who set up looms at home do not themselves get involved in carpet weaving. Requiring their children to work at home looms may enable unemployed fathers to stop looking for work. Children generally do not attend school and are rarely allowed to play during the day.

In Nepal, the number of children engaged in the carpet industry appears to have declined since 1994. Before the decline, child workers, mainly migrants from the countryside, constituted from one-third to one-half of the labor force in carpet factories. According to several sources, as many as 150,000 carpet workers were children, 10,000 to 27,000 of whom were in debt bondage as a result of loans taken by their parents from labor contractors or landlords.

By the end of 1994, negative publicity in Europe concerning the use of child labor and a resulting drop in Nepalese exports prompted the Nepalese Government and carpet manufacturers to try to eliminate child labor in carpet factories. As a result, the use of child labor in the carpet industry has dropped to five-ten percent of the total carpet labor force.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child states that children must be protected from all forms of economic exploitation. This includes performing any work “that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child’s education, or to be harmful to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development.” The Convention also calls for the prevention of the use of children in illicit production and trafficking of drugs, protection against all forms of sexual exploitation, and prevention against traffic of children for any purpose.

Views expressed are personal