Bridging the gap

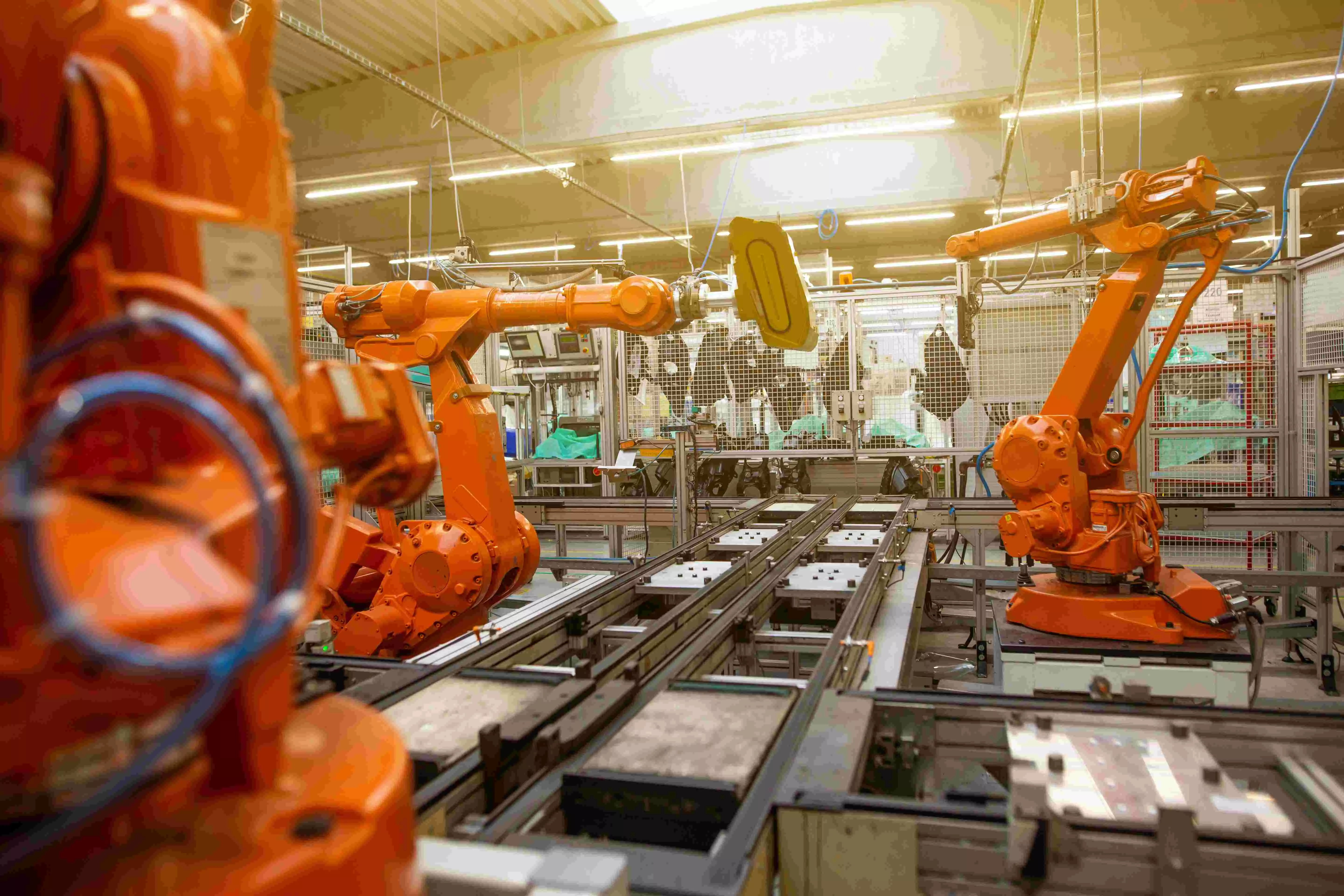

As India transitions from a primary sector-dominant economy to one dominated by the services sector, the role of the underdeveloped manufacturing sector in promoting growth should be defined coherently

India is the world's fifth largest manufacturing powerhouse, producing nearly USD 560 billion worth of goods per year, but our share in global manufacturing output is below 3 per cent. The share of manufacturing in India's Gross Value Added (GVA) is stuck at just 17 per cent, not far ahead of the share of agriculture. It is often stated that India seems to be transitioning directly from a primary sector-dominant economy into one dominated by the services sector. The question often asked is whether manufacturing is going to play its part in India's paradoxical and counter-intuitive growth story.

However, one element of India's industrial landscape is quite predictable. The concept of growth poles, first propounded by the French Economist Perroux, along with its accompanying concepts of the inevitability of unbalanced regional growth in industrial clusters, with an agglomeration effect that will accentuate regional diversity, seems pretty close to India's development experience. Thus, even where India had set up new industrial townships in places like Rourkela, Bokaro or even Jamshedpur in an earlier era, these do not appear to have led to broader regional development, with the nearby hinterland areas still remaining under-developed for the most part. The broader issue of regional disparities that have emerged in India have been sought to be addressed institutionally by the various Finance Commission's devolution formula which give overwhelming weightage to per capita income and, therefore, ensure higher resource flows into backward areas. The market, on the other hand, has responded to these disparities by the movement of migrant labour to the faster growing parts of the country, with the migrant labour being the unsung hero of the construction and manufacturing growth in these areas. Moreover, as the imperative of global supply chains has led to industrial production getting increasingly linked to international trade, the concepts of growth poles and growth centres are now being supplemented by the phenomena of port-led industrial growth with major ports, old and new, serving as growth centres in many countries.

The National Industrial Corridor Development Programme (NICDP) takes on the challenges of accelerating India's manufacturing growth, creating multiple industrial growth foci, and linking industrialisation to transport nodes, head on. The NICDP has focused on development of industrial townships adjacent to 11 key transport corridors. Eight such townships have been approved till the current year, four of which are shovel ready with the industrial plots being allotted, and four others are being implemented with trunk infrastructure being set up. As against eight projects implemented or under implementation over the last 17 years, the government has recently approved 12 such smart industrial cities in 10 states, at one go, with a big bang approach which is characteristic of PM Modi's style focusing on speed and scale. All these sites have been validated using the geospatial data on the PM Gati Shakti National Platform to minimise disturbances to existing habitations and ecology, with priority accorded to availability of land parcels with the state governments, covering land of relatively lesser agriculture value, with proximity to major transport modes for multi-model connectivity and having strong potential for backward and forward linkages with the neighbouring areas. A new aspect of using PM Gati Shakti to not only ensure enhancement of transport infrastructure (highways, rail links, airport links) for improved connectivity but also to combine such network planning with an area planning approach by asking states to start filling social infrastructure gaps (schools, Anganwadis, ITls, accommodation), concurrently with project implementation, has been initiated. This combination of transport network planning and area planning should lead to these greenfield industrial cities getting plug-and-play infrastructure and multi-model transport links ahead of demand for the private sector, and particularly for foreign investors who wish to participate in India's growth story.

It may be recalled that India's Ease of Doing Business (EoDB) ranking had improved from 143 in 2014 to 63 in 2020. Such rankings are published by the World Bank. However, in two key aspects of EoDB, land management and contract compliances, India's rank continues to be well above 100. While contract compliances and improvement are linked to the broader issue of judicial reform, the NICDP programme will substantially address, along with parallel initiatives by the states, the issues of land availability and its transparent administration for any investors seeking industrial sites in these cities. The NICDP Programme also de-risks the investor from one key compliance burden which new investors are concerned about, the issue of environmental clearances by ensuring that full environmental clearance for the entire township is already in place and is backed up by a full spectrum of utility services like power, sewage and waste treatment, roads etc., in a smart city with state-of-the-art infrastructure and digitised grievance redressal mechanisms.

The NICDP Programme, thus, has great potential for transforming India's industrial landscape, de-risking private sector investments in manufacturing, creating new growth foci in regionally dispersed locations on the backbone of the golden quadrilateral, generating potential investment of Rs 1.5 lakh crore and employment for 4 million people and, thus, helping cement India's emerging role in global supply chains.

The writer is former Secretary, DPIIT, and currently OSD, Ministry of Defence. Views expressed are personal