An incongruent bargain

Compensatory afforestation carried under the aegis of CAMPA is a flawed practice because it fails to capture the essence of broader ecosystem restoration

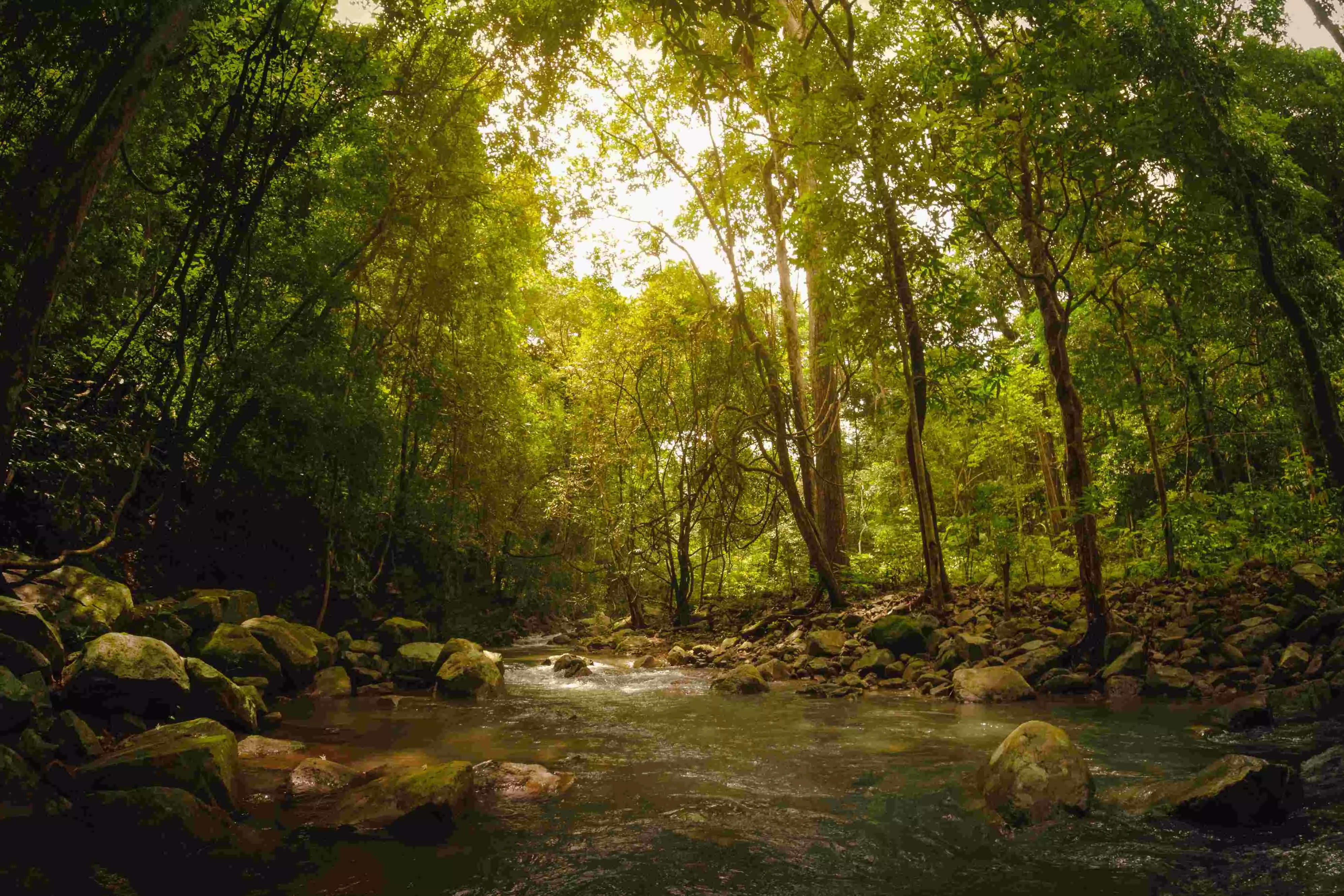

The UN has declared the 2020s as the ‘Decade of Ecosystem Restoration’ to highlight the importance of restoring degraded lands in mitigating climate change. Tree plantation is a key component of ecosystem restoration. However, it is essential to understand that restoration involves more than just tree planting. It encompasses a holistic approach that considers soil quality, water resources, biodiversity, and natural processes.

According to the Indian State of Forest Report 2021, India has witnessed a 0.28 per cent increase in forest and tree cover over the past two years — attributed to various afforestation programmes, including compensatory afforestation.

The National Compensatory Afforestation Programme, regulated by Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority (CAMPA) under the MoEF&CC, is India's largest afforestation initiative. It involves compensatory afforestation in exchange for forest land diversion, as per the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980. State forest departments undertake afforestation on degraded forest lands or non-forest lands using funds deposited by public and private companies as compensation for the loss of forests due to non-forestry activities. The Compensatory Afforestation Fund Act, 2016, requires payment of the Net Present Value (NPV) for lost ecosystem services by the user agency responsible for land diversion.

An amendment and its implications

The recently proposed amendment bill 2023, with respect to the Forest (Conservation) Act 1980, threatens vast tracts of forests and unclassed forests by exempting them from the purview of the Forest Conservation Act of 1980, which will facilitate diversion of these forest lands, leading to deforestation. The bill proposes to cover land that has been officially declared as forest under the Indian Forest Act, 1927, or under any other law, and recognises only forest lands recorded as such after October 25, 1980. Most states in the country are replete with rich biodiverse ecosystems that are essentially forests, and are managed as forests. However, they may not be recognised or notified, or are yet to be recognised or notified, as forests in government records. The provisions of the amendment bill also restrict the Act’s ambit by exempting land that is identified or used for compensatory afforestation. This raises questions about the transparency and accountability of CAMPA.

The landmark Godavarman case ruling by the Supreme Court of India played a crucial role in forest conservation in the country. This case identified an important fact — the cost of cutting a forest. While the ruling sought to make forest clearance more difficult, the current scenario suggests otherwise, much to the disappointment of activists, environmentalists, and researchers.

Kanchi Kohli, legal researcher at the New Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research, said in a recent interview that the concerns with the act can be understood as “prioritisation on unlocking government, private, and institutional land and then enclosing them as plantations than taking a proactive approach to minimise forest loss”.

Neglecting restoration

Forests are intricate ecosystems hosting immense biodiversity and are crucial for regional and global water cycles. In a recent interview, Onno van den Heuvel, the global manager of the UNDP’s Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN), highlighted the significant value of ecosystem services such as crop pollination, water purification, and carbon sequestration. These services are estimated to have a total annual value between USD 125 to USD 140 trillion, surpassing the global GDP.

A major concern regarding compensatory afforestation (CA) lies in the categorisation of all open canopy ecosystems as degraded lands, eligible for afforestation under the Forest Conservation Act Handbook 2019. This handbook considers lands with a crown density below 40 per cent as "degraded forest land" for the purpose of CA. It fails to recognise them as distinct ecosystems with their own biodiversity. Furthermore, it does not prioritise identifying the "drivers of degradation" as a prerequisite for restoration efforts. Believing that a complex ecosystem can be fully replaced through a few years of afforestation is a fallacy that has hindered reforestation and ecosystem restoration.

Strengthening CAMPA

Current afforestation policies prioritise quantity over appropriate species selection and post-planting care, neglecting biodiversity and ecosystem services. CAMPA aims to restore lost forest cover but overlooks biodiversity loss. Restoration-based afforestation is essential for preserving biodiversity and overall ecosystem health.

A study published in Science by Poorter L. highlights that the recovery of different forest attributes is influenced by distinct drivers or processes. Rapid successional development, or self-repair, is observed in sites where forest clearance has occurred relatively recently (in years rather than decades), where residual trees, seedling banks, and soil seed stores of native species still exist, and where intact, biodiverse native forests remain in the landscape.

Compensatory afforestation requires robust monitoring beyond mere plantation establishment. Integrating a Biodiversity Assessment Index (BAI) is recommended to measure ecosystem diversity effectively. However, CAMPA guidelines primarily monitor the growth of saplings and vegetation cover, without the ecological study of the area.

An analysis conducted by S Tambe and GS Rawat advocates using "compensatory restoration" instead of "compensatory afforestation" for scientific accuracy in the Indian context.

Jessica Gill is Senior Research Associate at Mobius Foundation; and Himani Kantiwal is Junior Research Associate at Mobius Foundation. Views expressed are personal