A puzzling gap

There is a large and growing gulf between cereal production and known uses of it

India produces about 300 million tonnes of cereals every year, but household consumption is barely 150 million tonnes. What is going on?

Before addressing this question, we should substantiate the figures. According to the official Foodgrains Bulletin of February 2024 published by the Department of Food and Public Distribution of the Government of India, cereal production (mainly rice and wheat) crossed 300 million tonnes for the first time in 2022-23 and reached 308 million tonnes in 2023-24. The latest three-year average of annual production (for 2021-22 to 2023-24) is 300 million tonnes.

What about household consumption? According to the latest consumption survey conducted by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), average per-capita cereal consumption was 9 kg per person per month in 2022-23: 9.61 kg and 8.05 kg per person in rural and urban areas, respectively. Assuming that India’s population was around 1.38 billion at that time, as projected by the National Commission on Population, total household consumption of cereals would have been around 150 million tonnes in 2022-23.

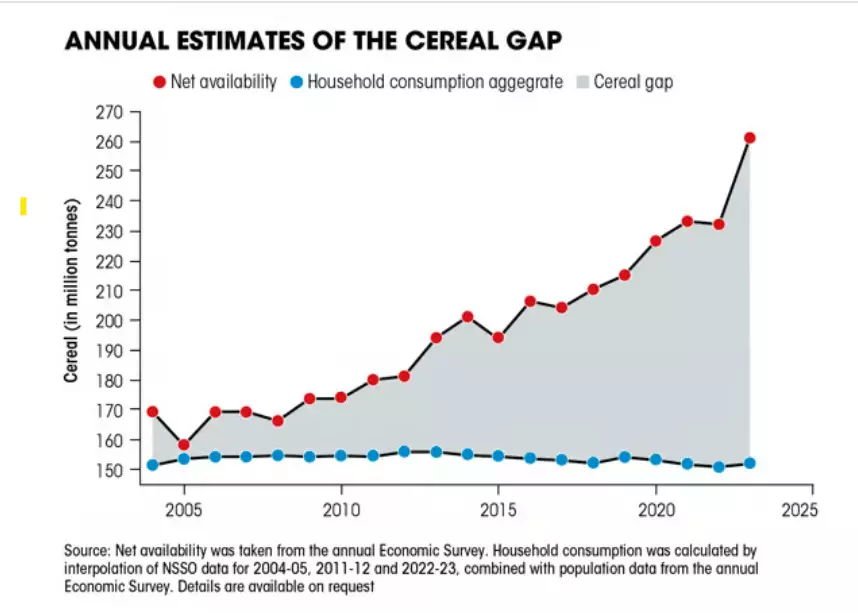

The Government of India’s annual Economic Survey traditionally deducts 12.5 per cent for seed, feed and wastage (SFW) to infer “net production” from gross production. Then it calculates “net availability” by adding net imports and deducting changes in public stocks. Until recently, net availability per capita more or less matched the NSSO consumption estimates. In recent years, however, a large gap — hereafter “the cereal gap” — has emerged between net availability and household consumption.

Annual estimates of the cereal gap are presented in the accompanying graph “Annual estimates of the cereal gap”. Here, per capita cereal consumption is assumed to decline linearly from 11.6 kg to 10.7 kg per person per month during 2004-5 and 2011-12, and then again from 10.7 kg to 9.1 kg per person per month during 2011-12 and 2022-23 — the NSSO estimates for these years. As the graph shows, the cereal gap started growing fast from around 2008 onwards. The graph ends in 2022-23, but provisional statistics for 2023-24 suggest that the cereal gap was above 100 million tonnes in both years.

It is worth noting from the graph that aggregate household consumption of cereals has been hovering around 150 million tonnes per year for many years — despite population growth. This is because population growth is compensated by the decline in per capita consumption (this declining trend stretches back to the late 1970s). Meanwhile, cereal production is increasing steadily, at a rate of around 2.5 per cent per year in the last 10 years. One outcome of this imbalance is a massive increase in cereal exports: nearly 30 million tonnes per year, on average, from 2021-22 to 2023-24. Another is the persistent tendency of public stocks to balloon, way above the official norms. Even after taking all this on board, 100 million tonnes of cereals are still unaccounted for every year.

Cereals, of course, have other uses than household consumption. Expert studies suggest that there is a case for doubling the feed component of the sfw allowance, from the traditional 5 per cent of gross production to 10 per cent. That would knock off 15 million tonnes from the cereal gap. Using production estimates from Statista.com, a global data and business intelligence platform and related sources, we can plausibly knock off another 8 million tonnes for grain-based ethanol production in 2022-23, 1 million tonnes for beer, and 1 million tonnes for “biscuits, bread, buns, cookies and croissant”. These are all upper bounds, especially for ethanol, considering that grain allocations for ethanol are partly reflected in the Food Corporation of India’s estimates of changes in public stocks. Adding all this up and deducting the total from 100 million, we still have an unexplained cereal gap of 75 million tonnes.

That’s a humongous quantity—enough to feed half-a-billion people for a year, or the entire population of Gaza for 250 years. By the same token, further allowances for “indirect” cereal consumption such as chowmein treats and restaurant meals are unlikely to be of much help in explaining the cereal gap.

Could it be that cereal production figures are exaggerated? The basis of these figures calls for urgent scrutiny. It would be surprising, however, if they were consistently off the mark by more than 10 per cent. Even at that rate, inflated production would not explain much of the cereal gap.

There is a related puzzle: if India is awash with cereals, as the cereal gap suggests, then why are cereal prices rising fast? The year-on-year inflation rate for the cereal component of the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) was 12.1 per cent in October 2022, 7.5 per cent in October 2023 and 8.1 per cent in September 2024 — considerably higher than the WPI for all commodities in each case. The cereal market, it seems, does not work in textbook demand-supply fashion.

The cereal gap is not just a statistical puzzle. For purposes of forward planning and price policy, India needs reliable estimates of cereal production and its uses. How are minimum support prices to be sustained if cereal production continues to grow much faster than household consumption? Is it possible and desirable to prolong if not amplify the recent binge of cereal exports? Has the time come for a major effort to diversify Indian agriculture away from rice and wheat? These and related questions are difficult to answer in a data fog.

There is another reason for concern. What if the cereal gap hides a scam of some sort? It looks like there is a “hidden guzzler” of cereals somewhere in the economy. Why would the guzzler hide, if the deed is above board? Hopefully, time will tell. DTE

Drèze is visiting professor at the department of economics, Ranchi University. Oldiges is the Senior Economic Affairs Officer at the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. Views expressed are personal