Telangana redux

Apart from linguistic grounds, the failure of Gentlemen’s Agreement fuelled discontent among Telangana political elites, conceding to whose demands, the Congress enraged Andhra elites

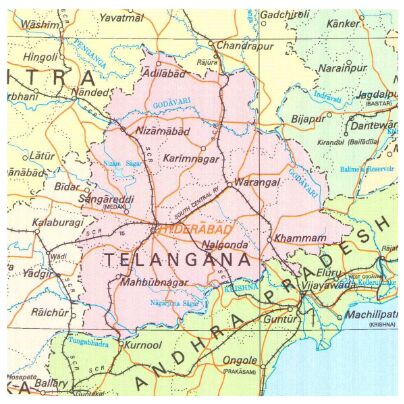

Political events make history, but history is also 'always in the making', as the present is contextualised in 'present continuous. This becomes so apparent when one looks at the 'imagination' of Telangana's history. While most observers would trace the history of the 29th state of India to 1955, when a section of intellectuals and the political leadership of erstwhile Hyderabad were wary of the attempts to merge it with the Andhra state, some have traced this to 1799, when Nizam had to give up his territories in coastal Andhra and the Rayalaseema region to the British in lieu of the tribute he had promised them for their support in his war against Tipu Sultan. In 1852, the decision was taken to build an anicut across the Krishna and Godavari rivers; this ushered unprecedented prosperity in this region — a sharp contrast to the nine districts which remained directly under the Nizam. When the Telangana movement was at its height, its adherents asserted that Telengana refers to Trilinga Desha — to celebrate the presence of ancient Shiva temples at Kaleshwaram, Srisaliam and Draksharamam. Even more credible is the argument that during the reign of the Nizam, the region was known as Telugu Angana, to differentiate it from the areas where Marathi and Kannada were spoken — for polyglotism was a hallmark of the Hyderabad state in which people spoke Urdu, Telugu, Kannada and Marathi.

As the formation of Andhra state in 1953 and Andhra Pradesh in 1956 has already been discussed, the genesis of Telangana can be traced to the failure of the Gentlemen's Agreement. The agreement was violated in both letter and spirit, and was one of the persistent tensions underlying the discourse of the sixties; was it possible for the political elite of a resource-poor region to ensure an agreement of this kind when the interests of the dominant elite are at stake. Linguistic determination was important, but development aspirations could not be overlooked.

Another factor that is often overlooked in the debate is the role of the then CPI, which was crucial in supporting the merger of the two regions. The party was guided by the Marxist notion of a 'linguistic nationality'. There was widespread belief that in the second general elections of 1957, there was a fair chance of the party being voted to power in the integrated state. What the comrades overlooked was the ability of the Congress to adopt the socialistic rhetoric, and befriend the leadership of the CPSU whose global interests were now aligned with those of Nehru, much to the chagrin of a section of the CPI leadership which later became the CPIM. As Hargopal puts it: "In the process, the dream of the Communist party for the formation of Vishalandhra became true, their hopes of coming to power were totally belied."

Meanwhile, given the success of the GR technologies in the Andhra districts which had assured irrigation, as well as access to seeds, fertilizers and markets, the region saw abundance, whereas the Telangana districts continued to lag behind. While the Andhra's moved from the subsistence mode to a market mode of production with enough surpluses to invest in agro-industries, manufacturing and real estate, including investments in Hyderabad, the other regions – Telangana, Rayalaseema and North Andhra — were still dependent on rain-fed agriculture, and the peasant mode of production. The extant Hyderabad elite — Punjabis, Marwari and Guajarati — also joined hands with the Separate Telangana agitation which reached a crescendo in 1969. Led primarily by students and government employees, citing violations of the Agreement and discrimination in education and employment, the agitation claimed over 350 lives. Mari Chenna Reddy broke ranks with the ruling Congress party to establish the Telangana Praja Samithi (TPS) to spearhead the movement. Gandhi, who was then at the helm of both the government and the party, was opposed to the division of the state. She accommodated the Telangana leadership – both in the party and government. In a bid to assuage the Telangana sentiment, Narasimha Rao was brought in the place of Brahmananda Reddy. This also marked the beginning of the complete domination of the Congress high command, and the end of the regional satraps in the Congress which, in the long run, led to the rise of regional parties in both Andhra and Telangana.

Narasimha Rao decided to go ahead with land reforms and redistribution which, till then, had never been strictly enforced. Enraged by this shift in leadership, and the threat of land reforms, Andhra elites started their own parallel Jai Andhra agitation in 1971-72, also seeking a bifurcation of the state. As they could not directly challenge the question of land reforms, they questioned the validity of Mulki rules in the city of Hyderabad. To start with, the employee's federations of Andhra filed cases in the High Court challenging the legal validity of the Mulki rules. While the High Court declared these rules as ultra vires, the Supreme Court upheld their validity, but so strong was the Andhra lobby that they were able to prevail upon the Parliament to amend the law and declare that the rules would not be valid any more.

Views expressed are personal