Out of political consensus

Consent among leading parties capped the efforts of JMM and others to realise the formation of Jharkhand — though covering a narrower area

The first General Election of 1952 firmly established the political dominance of the Jharkhand Party (JHP) in the region, and soon thereafter, laid the ground for the creation of a separate province. The culmination of this campaign was a well-attended demonstration by the tribals in 1955 in Ranchi to demonstrate the numerical support for a separate state before the States Reorganisation Commission (SRC). However, the SRC also had to face counter-demonstrations that favoured the integrity of Bihar. The anti-Jharkhand camp accused the 'Jharkhandis' of playing into the hands of foreign missionaries. There were quite a few contradictions at play — tribal and non-tribal — and within the tribals, there was a conflict based on Christian and non-Christian tribals — and within the Christian tribals, there were issues between Catholics and Protestants.

Be that as it may, the JHP submitted a memorandum to the SRC, stressing the economic, socio-political and cultural grounds for demanding the creation of a new state. It emphasised that linguistically, culturally and ethnically; the tribal population was separate from the non-tribal people, and hence, geographical contiguity and a separate administrative unit was required. Here again, the dilemma was apparent — while on the one hand, the JHP was trying to mobilise people on the issue of Jharkhand, it was also eager to secure the support of both tribal as well as non-tribal population. The SRC did not pay any heed to the cultural distinctness of the region and built its case purely on the lingual basis of reorganisation. Hence, the claim of the Jharkhandis for a separate state was rejected on grounds that the multiplicity of tribal languages did not permit the creation of a new state in the Jharkhand region.

The failure of JHP in convincing the SRC affected its popularity. Gradually, even its key supporters began to doubt the intentions of the JHP and its leaders, and a mood of disillusionment was set in. The final nail in the coffin was the merger of JHP with INC in 1963 as a quid pro quo for a ministerial berth in the Vinodanand Jha's Bihar cabinet for Jaipal Singh!

Although the JHP was merged into the INC, many splinter groups appeared on the firmament, and representations were made to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1969, and again in 1973 by Jharkhand Party leader N.E. Horo. This was followed by a third representation by the Jharkhand Coordination Committee leader BP Keshri in 1989 to the President of India.

Meanwhile, the 70s saw the second phase of the movement. Here, the issues of farmers and workers were at the forefront, and the political demand for Jharkhand took a back seat. The ever-increasing resource extraction from Jharkhand, massive displacement of the indigenous and other rural population, and the unprecedented exploitation of miners and unorganised industrial workers were the immediate cause of the emergence of the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (literally Jharkhand Liberation Front) under the mentorship of the Marxist AK Roy, Kurmi leader Binod Bihari Mahto and the tribal supremo, Shibu Soren. While Mahto successfully brought the Kurmis into the fold of the Morcha, Shibu Soren, a charismatic Santhal leader became instrumental in forging a Santhal-Kurmi unity. However, the epicentre of the movement shifted to form the tribal-dominated Ranchi and Dumka to the mining and industrial belt around Dhanbad, Bokaro and Jamshedpur.

The JMM also demanded statehood, but this was not a primary tool of mobilisation. Instead, the JMM sought to provide leadership to existing protest movements. They also appealed to a common identity of Jharkhandis as "workers" in both rural and urban areas. The main ideologue, AK Roy argued that the Jharkhand "nation" was suffering from a situation of "internal colonialism," exploited by outside interests.

This consolidation did not last long because of serious ideological differences and personality clashes between the three very strong leaders, all of whom wanted the movement to have a different orientation. AK Roy was opposed to capitalism itself, Shibhu Soren wanted to dispense 'instant justice' and the ouster 'dikus' from tribal lands, and Mahto was keen on electoral politics. As such, the movement petered out.

The 80s saw the emergence of the Jharkhand Coordination Committee (JCC) and the All Jharkhand Students' Union (AJSU). These were movements for the assertion of the 'Jharkhandi identity' and they consciously eschewed politics.

More than this, it was the mainstreaming of the statehood demand by the leading opposition party, the BJP — which till recently had been opposing the formation of new states in the country — gave a boost to the formation of Jharkhand. In the first three decades after Independence, the Jana Sangh and RSS were opposed to the linguistic reorganisation of states. They regarded it as a fissiparous tendency. However, in both Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, the BJP found it easier to mobilise support in the newly established industrial townships, as well as in mining and irrigation project areas, for these were the places to which the new migrants, professionals and workers were attracted. Another reason why the BJP and the RSS became active in these regions was to prevent any further proselytisation attempts.

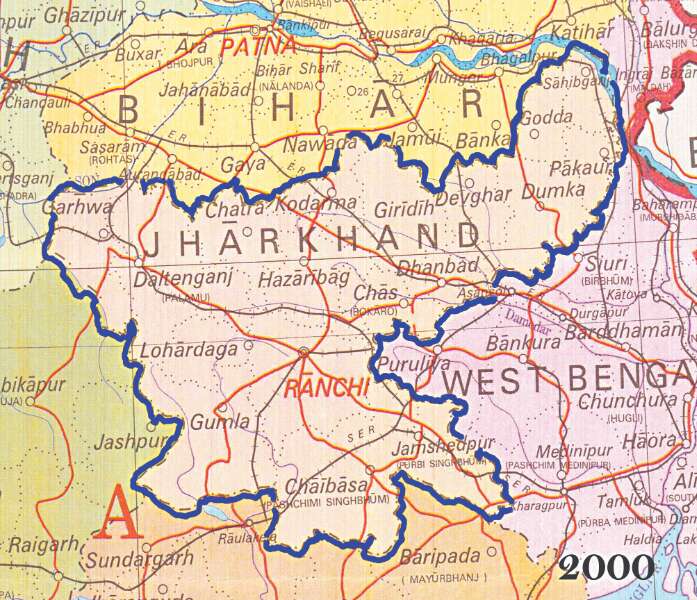

Thus, the bifurcation of the state had the bipartisan support of both the Congress and the BJP, and though the RJD had its initial reservations, there was a rare political consensus in the country at the turn of the century with regard to the formation of the three new states, of which Jharkhand was the largest. Thus, as per the Bihar Reorganisation Act, 2000, on the appointed day of November 15, 2000, which coincided with the birth anniversary of Birsa Munda, the great Adivasi leader, the state of Jharkhand was carved out of Bihar. Jharkhand had a population of about 2.2 crore and an area of about 80,000 sq km which was half of the territory of Bihar. However as the districts in Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal and Orissa were not touched, it could be said that the demand for Jharkhand was fulfilled substantially, but not fully!

The writer is the Director of LBSNAA and Honorary Curator, Valley of Words: Literature and Arts Festival, Dehradun.

Views expressed are personal