Curtailed autonomy

Following the contentious recommendation of the SRC in 1956 a abolish the legislative assembly and reduce Delhi’s autonomy to Municipal Corporation, the national capital finally came to be governed through ‘elected councillors’ in ‘advisory role’ to the lieutenant governor from 1966

As discussed in the previous part of the column, New Delhi got its legislative assembly and council in 1952 after a long struggle. However, the national capital's tryst with autonomy was short-lived. It must be placed on record that in 1956, a resolution of the Delhi Legislative Assembly "recommended to the Government of India that boundaries of Delhi state be enlarged to include the neighbouring districts of Punjab and UP so that an administratively and economically sound state is created". A memorandum submitted to the SRC on behalf of the Delhi state government asserted, "the people of this area (Delhi and the surrounding districts) have historic, cultural and economic ties. They have common language, dress, marriage rites, laws of succession, system of land tenure and customs." The representation went on to add that the province of Delhi had been broken up artificially "both as a punishment for taking part in the so-called Mutiny of 1857, as well as a device to break down their morale and to crush their spirit". The proposed territories included the Agra, Meerut and Rohilkhand Divisions of UP; the Ambala Division of Haryana and the Alwar and Bharatpur Districts of Rajasthan. This proposal did not find a positive response, either from the Union government or the states of UP, Punjab and Rajasthan. Meanwhile, a similar memorandum was submitted by 97 MLAs from the western and hill districts of UP wanting to merge their areas with Delhi. The five points made in favour of their demand were: a) The sheer size of the state (UP), which often led to the neglect of the Western districts and the hill areas; b) lesser development expenditure; c) need for rapid industrialisation; d) geographical proximity to Delhi rather than Lucknow and e) the new state would not develop a new capital, for Delhi could serve the purpose.

The news that a hundred legislators could get together and submit a memorandum to the SRC, caught the state and the Central leadership of the Congress unaware, and they stepped in immediately to stall the move. The UP Congress' strongmen PD Tandon and GB Pant closed ranks, and nipped this in the bud, and gave a counter memorandum to the SRC on why the territorial boundaries of UP should remain unchanged. They averred that the large size of UP was good for large-scale development projects and mobilisation of resources. While the Chairman of the SRC, Justice Fazal Ali, and HN Kunzru were convinced with this argument, the third member, KM Pannikar gave a strong note of dissent. He made the point that UP was too large to be administered. It may be noted that earlier, Dr Ambedkar had expressed the view that a state of the size and population of UP was creating political asymmetry. Had the views of Dr Ambedkar, as well as that of legislators of UP and Delhi prevailed, the political geography of India would have been quite different from what it is.

Unsurprisingly, SRC's recommendations of abolishing legislative assembly and reducing the national capital's autonomy to the level of Municipal Corporation invited the strongest criticisms from key figures from Delhi. Reacting to the Commission's report tabled in the Parliament, Member of Parliament Sucheta Kriplani raised her concerns against the change of Delhi's status: "Delhi is going to lose its democratic setup. We are going to lose the status of State. Our people will be disenfranchised. In place of the legislature, we are going to be given a Corporation with limited powers. Therefore, I feel Delhi is not being dealt with fairly." Another lawmaker, CK Nair, observed: "But what we expected is a fair deal for Delhi just as every Part C State was added to Part A State, which means greater advantage and greater freedom for people of those areas. It is not so with regard to Delhi."

To give Delhi some elected leadership, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi Act, 1957 was passed by the Parliament, establishing the now-trifurcated Municipal Corporation of Delhi. Delhi, however, did not come under the Government of Union Territories Act, 1961, which allowed for legislative assemblies and councils of ministers in some large union territories. There were widespread demands for Delhi to get statehood and more elected representatives in its general governance.

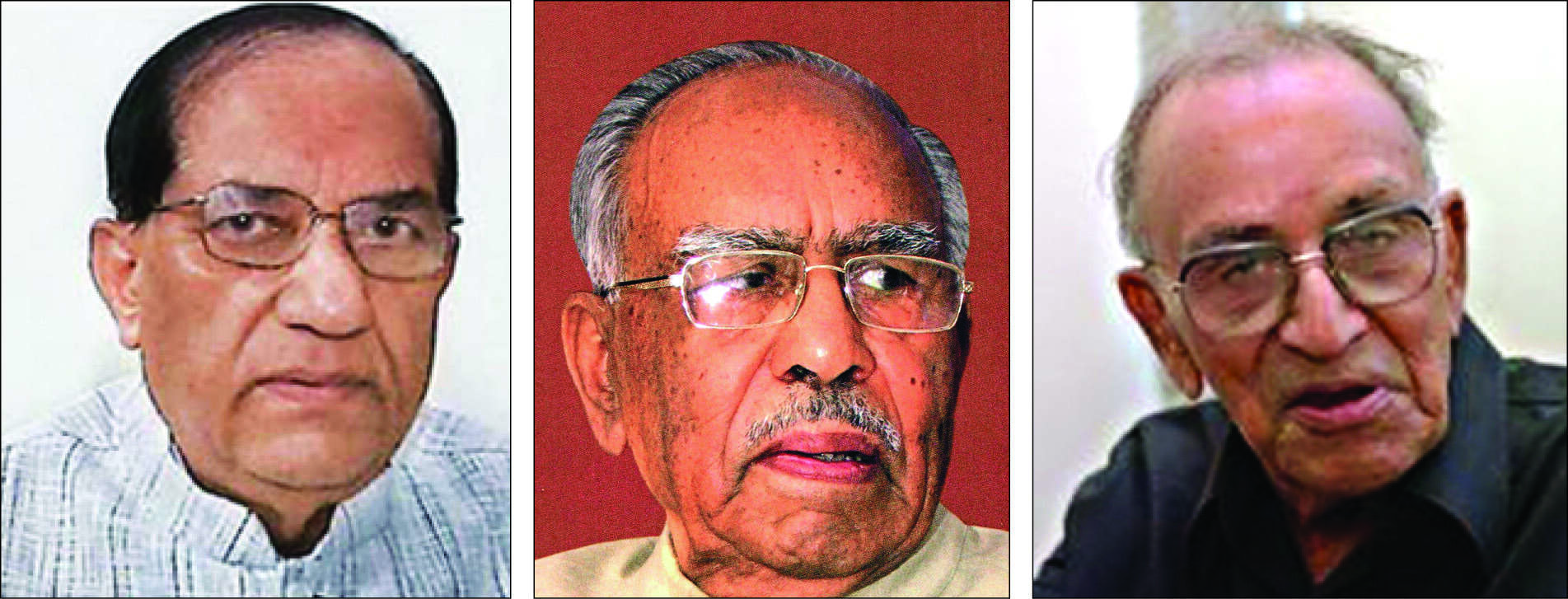

As a compromise, the Delhi Metropolitan Council was formed in 1966 with the passing of the Delhi Administration Act, 1966 by the Parliament of India. The council had 56 directly-elected members (called councillors) and five members nominated by the newly-created position of lieutenant governor (LG). The council had only advisory powers with regards to legislative proposals, budget proposals and other matters referred to it by the lieutenant governor. The lieutenant governor succeeded the chief commissioner as the administrator of Delhi. The Delhi Metropolitan Council's chairman and deputy chairman acted as speaker and deputy speaker for the council, which elected a chief executive councillor and three executive councillors, much like a state chief minister and council of ministers elected by — and responsible to — Sabhas. During this twenty-four-year period, the Chief Executive Councillors emerged as the 'de facto' political leaders of Delhi with VK Malhotra and Kedar Nath Sahni of the BJP and Jag Parvesh Chandra of the INC holding the position for significant periods of time.

Views expressed are personal