Coming together in cohesion

Colonial encroachment of rights and resources partly united the forest locals in the historic region but concrete demand for a separate state could take shape only after Independence

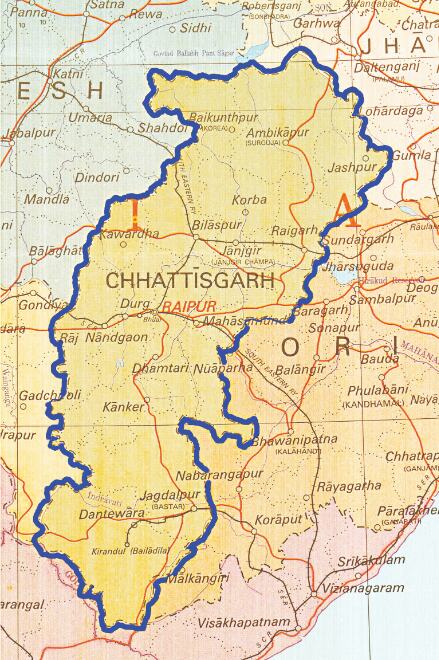

Formed on November 1, 2000, as a state carved out of Madhya Pradesh, the region was described as Chhattisgarh — or the region with 36 forts, in inscriptions, literary works and foreigners' travelogues. Covering an area of 1,35,000 sq km and a population of about 20 million, it was the largest of the three news states of Uttarakhand, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh formed that year. New states included the 16 eastern districts of MP, which lost about one-third of its territory and population to Chhattisgarh. The state's lineage can be traced back to the legendary Dakshin Kosala, the kingdom of Rama's mother Kausalya, as well as Dandakaranya, where he, along with Lakshman and Sita had to spend fourteen years in exile. The capital city Shripur (etymologically the city of wealth) on the banks of Mahanadi became an important centre of Buddhism, at par with Nalanda, for its hundreds of monasteries and thousands of monks from the fifth century BCE to the 12th century CE. From the 12th century, the Chedis and the Chalukyas ruled the region directly, and then came under the suzerainty of the Mughals from the 16th century. By the late 18th and early 19th century, the British extended their colonial enterprise to this region. As Nadine Sunder, an insightful scholar and chronicler of contemporary Chhattisgarh puts it 'the colonial situation meant that the primary impulse for extension of administration did not come from the changing exigencies of local society, but from the colonial authority's perception of the necessity to govern'. The superabundant forest wealth drew the colonial gaze, and thus began the 'reservation of forests, organised timber felling, infrastructure for hunting, and the systematic curtailing of rights of forest dwellers over the forest produce' — thereby upsetting the ecological balance and livelihood opportunities of the forest dwellers. These conflicts over traditional rights to forest produce versus the 'legal grime of the colonial state' often led to revolts and rebellions, which were intense and violent, but spatially confined to the region. However, the central narrative remained common and unchanged — the inalienable right of tribals over local land, resources and forests. The Bastar tribals, therefore, sought a separate state of Gondwana but the movement petered out as they could not mobilise political support from the Congress or Acharya Kirplani's Kisan Mazdoor Praja Party (later Praja Socialist party) which was the lead opposition in the region. Also, they could not make common cause with the predominantly rice-growing plains around Raipur, where political mobilisation for Chhattisgarh had started from the 20s and their conception of Chhattisgarh included the forest and

hill regions. It may also be mentioned that while Raipur and the adjoining plains were part of the erstwhile Central Province and Berar, the tribal areas came under a variety of princely and feudatory states and were also linguistically and geographically separated.

The first stirrings of the national movement in the region were felt when Mahatma Gandhi toured Raipur on December 20, 1920, to mobilise support for the Khilafat and Non-cooperation movements, and to raise resources for the Tilak and Swaraj funds. He was accompanied by the Ali brothers, and the arrangements for the conference were made by the political stalwart of the region, Ravi Shankar Shukla, who later became the Premier of CP and Berar and the first CM of Madhya Bharat. A flavour of the times is captured in the repartee of Ravi Shankar Shukla to Asgar Ali who thanked the Hindu brethren of Raipur for supporting the Moslem cause of the Khilafat. Shukla responded — We do not consider ourselves Hindus or Moslems, we are all Hindustanis.

This led to the formation of the Raipur District Congress Committee, which raised the demand for a separate province of Chhattisgarh in 1924. This was also raised in the Tripuri session of the Congress but did not gain much traction on account of the domination of Shuklas in the larger arena of state and national politics.

Nevertheless, a memorandum was submitted to the SRC in 1954, and the demand for a separate state came up in the Nagpur assembly of the then state of Madhya Bharat — which was in many ways — the reiteration of a demand that had been raised in the CP & Berar assembly before Independence as well. But, even though the demand was not accepted by the SRC, the 'seed had been sown'. Unlike most together states where the demand for linguistic states took violent forms, a bipartisan consensus on the new state was formed over the next three decades, and the separation from MP took place with the least acrimony.

Incidentally, the reason which the SRC gave for rejecting the Chhattisgarh demand was that Madhya Pradesh would not be economically viable without the forest and mineral wealth of Chhattisgarh!

The writer is the Director of LBSNAA and Honorary Curator, Valley of Words: Literature and Arts Festival, Dehradun.

Views expressed are personal