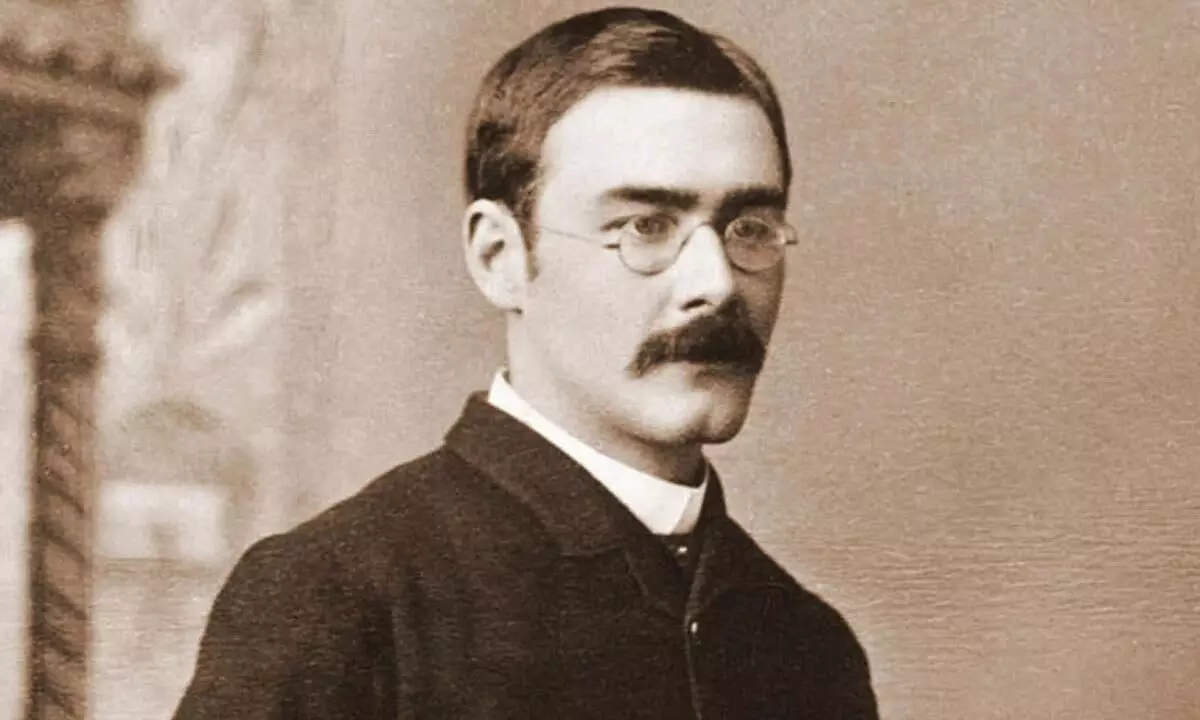

Rudyard Kipling & the Heavily Armed Thakur

Rudyard Kipling’s Rajputana travels gave him stories that would help shape his literary legend

When we talk about foreign correspondents braving hostile terrain, we often imagine modern war zones or authoritarian regimes. Rarely do we recall that one of the most handsomely paid and widely travelled reporters in 19th-century India was a 22-year-old Rudyard Kipling - armed not with a flak jacket but with a princely salary of Rs 600 and a mandate to wander through the semi-independent states of Rajputana.

In 1887, Kipling was transferred from the ‘Civil and Military Gazette’ in Lahore to the ‘Pioneer’ in Allahabad with explicit orders: explore Rajputana, observe its princely states and write. The result was the celebrated ‘Letters of Marque’, 19 articles chronicling his zig-zag journey from Jaipur to Udaipur, Chitor, Ajmer and Jodhpur. The title borrowed from the license issued to privateers, a fitting metaphor for a young journalist navigating lands where the British Raj’s reach was thin and its protection thinner.

Kipling’s restlessness drove him from rail to tonga and from horse to elephant, often alone and almost always unable to communicate with the people around him. He admitted in a letter to his cousin that he had not seen a ‘white face’ for six days, an admission that doubles as a reminder of the cultural and psychological isolation colonial writers often romanticised but rarely confronted head-on.

Yet nothing prepared him for the most gripping scene of his Rajputana odyssey: a broken mail-tonga wheel in the middle of 70 miles of scrubland, on a bitterly cold night, with the soldier escort and the driver both vanishing into the darkness - leaving Kipling as the lone guardian of the British mails.

There he perched, on a pile of parcel bags, shouting threats into the void. As scholar John Montefiore notes, Kipling’s ‘terrible voice’ was swallowed by the night, leaving ‘only a thin trickle of sound’. The bags, Kipling felt, were his last tether to civilisation - proof, perhaps, that the empire’s agents often found themselves more emotionally dependent on its symbols than its subjects ever were.

When rescue did arrive, it was hardly reassuring: a heavily armed Thakur and his retinue, who reluctantly agreed to take the stranded Englishman and the mailbags aboard. Kipling spent the next eight hours being jostled, prodded and addressed as ‘thou’, a discourtesy that struck him more sharply than the revolver casually worn by one of his Rajput companions. Under British rule, such a weapon was contraband for a ‘native’. Out here, in the borderlands of empire, such rules mattered little.

This is the irony at the heart of Kipling’s desert journey: the empire’s chronicler was at once its representative and - in moments of isolation - its most helpless subject.

When Kipling returned from the wilderness, sunburnt and shaken but triumphant, he met an indignity far worse than discomfort - celebrity. His name blazed across railway hoardings. Newspapers feted him. Dinner hosts sought to display him like an exotic trophy. For a writer who despised the machinery of fame (a contrast to many of today’s publicity-hungry journalists), this was nothing short of mortification. He later wrote, with obvious distaste: “If you had your name placarded up and down 2,200 miles of line, you wouldn’t feel happy.”

Kipling’s Rajputana travels gave him stories that would help shape his literary legend. But they also offered a glimpse - rare, unvarnished - of the empire’s uncomfortable truth: that even the loudest champions of British authority were sometimes reduced to frightened travellers in the night, at the mercy of men who owed them no deference.

In that moment, shivering atop mailbags under the indifferent desert sky, the young Rudyard Kipling met his match - not in danger, but in humility.