Historic show to unveil 250-year-old hand-carved wooden blocks

Nearly 220 years after his death, the invaluable work of Panchanan Karmakar, including hundreds of the first ‘harafs’ or blocks he etched that led to the first-ever book in Bengali and subsequently gave the world a manual to learn the language, will be opened up in an iconic show by his great-great-granddaughter Priyanka Mullick

In a historic first, the wooden blocks - hand carved and as tiny as a centimetre in size that gave the world the Bengali language in printed form - will be brought out for public viewing this January. Nearly 220 years after his death, the invaluable work of Panchanan Karmakar, the man called the Father of Bengali typography, including hundreds of the first ‘harafs’ or blocks he etched that led to the first-ever book in Bengali and subsequently gave the world a manual to learn the language, will be opened up in an iconic show by his great-great-granddaughter Priyanka Mullick. Karmakar passed away in 1804 at the age of 54. Kept invisibly for over two hundred years in his house in Serampore, the original machines were used to develop the first-ever typeface for print in Bengali.

The wooden Bengali alphabet and typeface developed by Karmakar were used until Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar created a simpler version in later years. An English typographer and Orientalist who supervised Karmakar’s work was Charles Wilkin. He was also the first translator of the ‘Bhagavad Gita’ into English and introduced the term ‘Hinduism’. Interestingly, Karmakar later developed typefaces in more than 40 other languages including Indian, Arabic, Persian, Burmese, Japanese and Chinese.

Karmakar’s work enabled the printing of the first-ever book in Bengali, ‘The Grammar of Bengal Language’, by Nathaniel Brassey Halhed. It also enabled the printing of Bengal’s first newspaper, ‘Samachar Darpan’. The advent of the typeface also birthed several local press and newspapers which became the voice of the common people in Bengal and later contributed politically. Karmakar also developed the first ‘Nagari’ type in India to print William Carey’s Sanskrit grammar. With Karmakar's help, the ‘Serampore Mission’ established a foundry for making type, which eventually became Asia’s largest type foundry.

The show, called ‘Haraf’, which will open first in Kolkata in January 2025, will then travel across India and the world.

Mullick, now in her 20s and working with the ‘National Centre for Performing Arts’ in Mumbai, has inherited all of her great-great grandfather’s original objects of tremendous historical value for both Bengal and India. She has returned to their ancestral home in Serampore and will unveil the whole lot in the iconic exhibition in Kolkata this winter.

“Unfortunately, Karmakar isn’t as famous as he should have been. He is often featured in the list of ‘Forgotten Heroes of Bengal’. Although he is acclaimed to be the ‘Father of Bengali typography’, there is only a handful of Bengalis who seems to know him. Moreover, Karmakar later developed typefaces in more than 40 other languages including Indian, Arabic, Persian, Burmese, Japanese and Chinese. So, his contributions are not limited only to the borders of Bengal. While it may seem that he was just a fine sculptor, his invention of the Bengali typeface was a game changer,” she said.

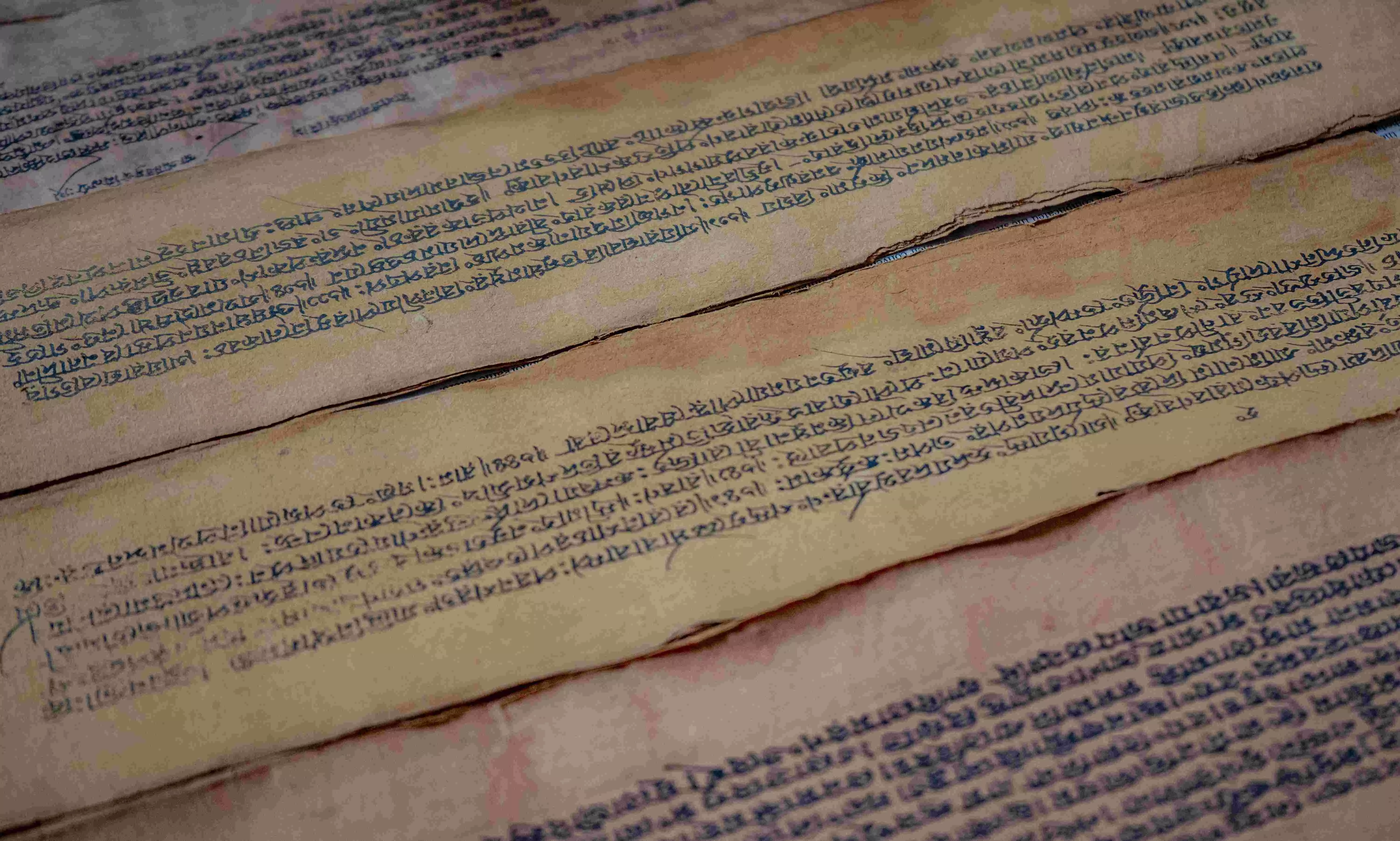

Mullick added, “I’ll exhibit Karmkar’s invention - the typeface, the Bengali types that were carved by him; a copy of ‘Samachar Darpan’, the first ever newspaper published in Asia; a copy of the first book that was printed in Asia, ‘A Grammar of Bengal Language’; the hand-moulds, built based on the Johannes Guttenberg technology of printing and a demonstration of how the fonts were produced in bulk from one mother type carved by Panchanan. I’ll also show carving equipment used in the type foundry besides the big machines, which were later sent by the British government to enable bulk production of types to boost printing. The show will also have scripts in Bengali on handmade paper and palm leaves that were used for formal communication before the advent of printing on paper. One of the most interesting objects to go on display will be the motherboard of Bengali types that were used in the ‘Adhar Type Foundry’ (Adhar Chandra Karmakar was the son of Panchanan’s brother).”

“Given that I am the only daughter of Biman Mullick, there is no certainty of a legal/natural heir at this point. There are no takers beyond my capacity and this piece of history lost will be a collective loss for Bengal and the country. Not just the physical remains of the foundry, but even the lineage will end with me. The artefacts are close to 250 years old and subjected to constant decay. If they lack the atmosphere and supervision, they might grow fragile. Most importantly, in case of any theft or misplacement, these artefacts will be sold in some market for the price of scrap, as it has been in the past,” she continued.

According to Mullick, Karmakar’s contributions aren’t limited only to the borders of Bengal. While it may seem that he was just a fine sculptor, his invention of the Bengali typeface was a game-changer for the following reasons. “I want to exhibit the remains of the type-foundry and the typefaces developed by Panchanan Karmakar. It’s a treasure trove of our past to be recognised and celebrated. While my family, especially my father, effortlessly tried to save the historical artefacts, it isn’t just ours; the history belongs to Asia, India and most importantly, Bengal. As we strive to maintain the status of Bengal as a leader in art, culture and literature, this collection is a stark reminder of Bengal’s contribution in the fields of calligraphy, printing, journalism and mass education in the country.”

Mullick wants to get Karmakar the posthumous recognition that he deserves. “While notable personalities like Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and William Carrey are celebrated and duly so, for their incredible participation in establishing printing presses, Panchanan Karmakar is a very niche name. Through the support of heritage groups, stalwarts of literature in Bengal and support of the government, I aim to make Panchanan a household name in Bengal and introduce a section on him in the syllabus of journalism. I’ll soon start an awareness campaign through the presence of this collection at literature fests, biennales and cultural forums in India, Asia, Britain and Denmark, with whom we have a common history and celebrate the legacy of Panchanan who enabled printing in Asia, for a radical change in journalism and education.”

Karmakar belonged to a family of sculptors who were in the business for several generations. He was known for the finesse he delivered in his sculptures and had sharp skills in carving very intricate and delicate designs on metals. When the British were scouting for artists and sculptors who would replicate the Gutenberg technology, their craftsmen failed to design the Bengali font on the narrow tip of a metal/wooden block. “Following this, they started to source local artists in Bengal who failed as well. A gentleman then recommended the British officials to meet the Karmakar brothers and give it a try. While the officials hesitated to appoint the brothers to this mammoth task given that both brothers were quite young, they were delightfully surprised when the first batch of Bengali fonts were delivered. After only a few attempts, Panchanan did the impossible, develop the first ever typeface (‘Haraf’) for print in Bangla,” she concluded.