Onset of the poll carnival

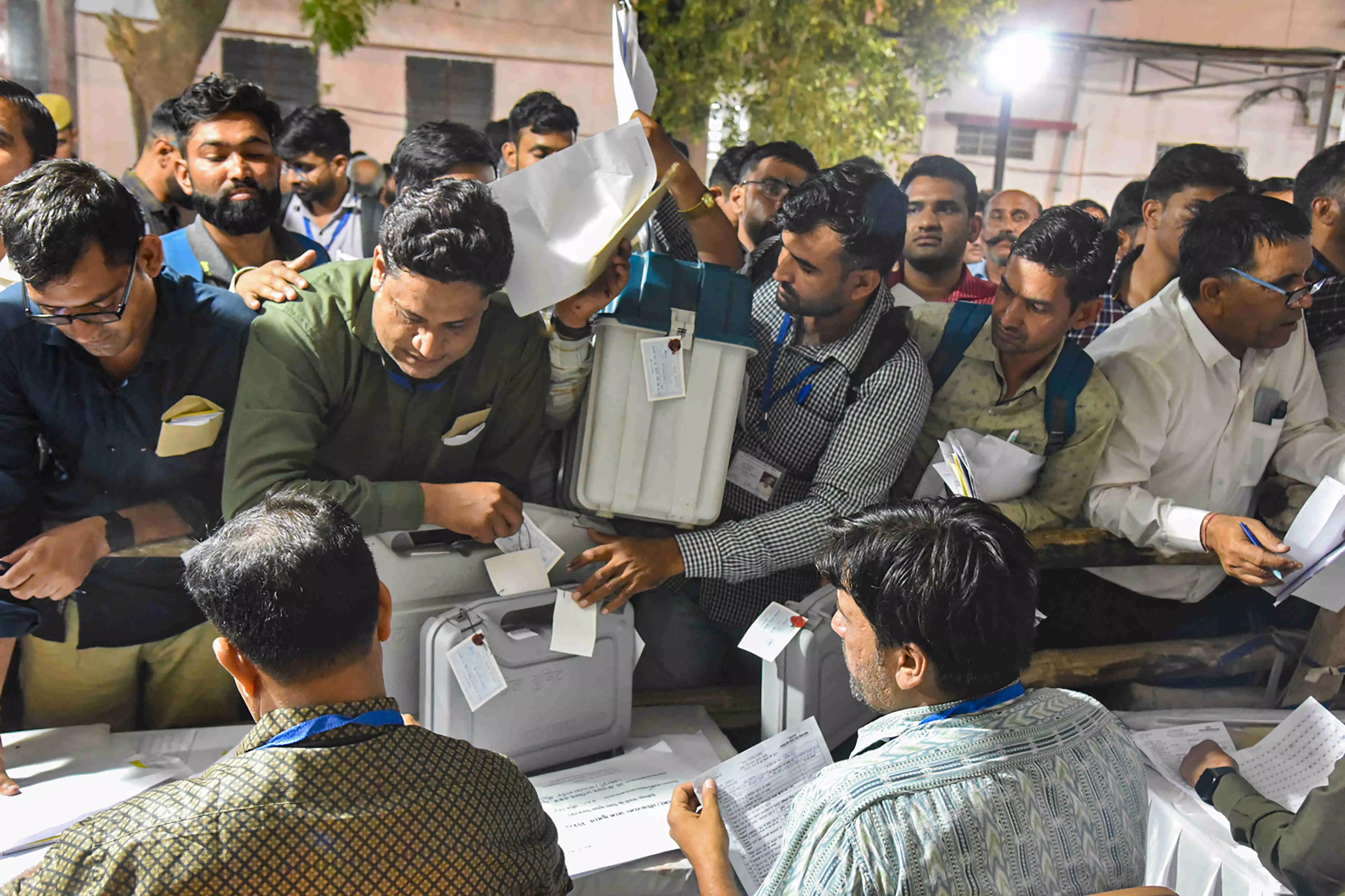

As the democratic carnival unfolded across the vast expanse of India in the first phase of the Lok Sabha elections, it brought to the fore both the vibrancy of its electoral landscape and the dull components that have, unfortunately, persisted through the decades post-independence. When a democracy of India’s stature goes for polls, all eyes are bound to be glued to the corresponding developments. Covering 102 constituencies across 17 states and four Union Territories, the first phase witnessed a mosaic of events ranging from the enthusiastic participation of the electorate to sporadic incidents of violence and technical glitches, and even election void.

Poll officials in Madhya Pradesh went an extra mile in extending the warm gesture of garlanding voters and applying tilak on their foreheads—an acknowledgement of their effort to brave heat and humidity while reaching the polling booths. Madhya Pradesh witnessed a voter turnout of over 63 per cent. The state had registered 61.57 per cent voting in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, which increased to 71.16 per cent in 2019. It must be noted that polling for three more phases in the state will take place on April 26, May 7 and May 13.

In sharp contrast, poll officials in six eastern districts of Nagaland had to wait in vain for nine hours in booths, as none of the voters would turn up following a shutdown call demanding for ‘Frontier Nagaland Territory’ (FNT). Boycott of such nature is a slap on the face of democracy, and also exposes the failure of the State in meeting the grievances of the marginalised population, with their voices remaining largely subdued. That they had to abstain from voting to make their voices heard is a discouraging sign.

In a similar vein, residents of Dhadkahi, dubbed the ‘silent village’ in Jammu and Kashmir's Doda district due to its deaf-and-mute population, voted in the Lok Sabha polls, hoping just for basic amenities. They threatened to boycott future elections if their demands — which are as basic as roads, water, healthcare facilities and education — are unmet. This shows yet another colour of the Indian electorate, presenting a scenario where hope and trust in democracy are teetering on the brink, just waiting to fade away if not bulwarked.

In the first phase of elections, it can be said that the election machinery more or less failed to carry out smooth voting in the regions reeling under socio-political and ethnic turmoil. Three of several such regions being Bastar in Chhattisgarh, the entire state of Manipur, and certain parts of West Bengal where the BJP and TMC are known for bitter contests. In the most unfortunate incident, as per news reports, an assistant commandant of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) was killed when an improvised explosive device (IED) planted by Naxalites went off in Bijapur district. Chhattisgarh saw a vote percentage of above 63 per cent.

West Bengal, standing true to its reputation of being home to one of the most politically aware electorate in the country, registered a voter turnout of above 77 per cent. Bihar, in sharp contrast, registered only around 46 per cent votes. Polling in West Bengal’s Cooch Behar was marred by violence, and both the TMC and the BJP clashed and lodged numerous complaints against each other for poll violence, voter intimidation, and assaults on poll agents. Voting in Manipur, as anticipated, was also marred by violence, but the state registered above 68 per cent votes.

India is a full-fledged, mature democracy where such disruptions should not be overlooked as being usual hiccups. The time has come to swiftly weed out such happenings during elections. The first phase of elections has concluded with a mixed bag of outcomes—setting the tone for next phases. As we proceed, the balance must now tilt towards the positive side.