Forging the Future

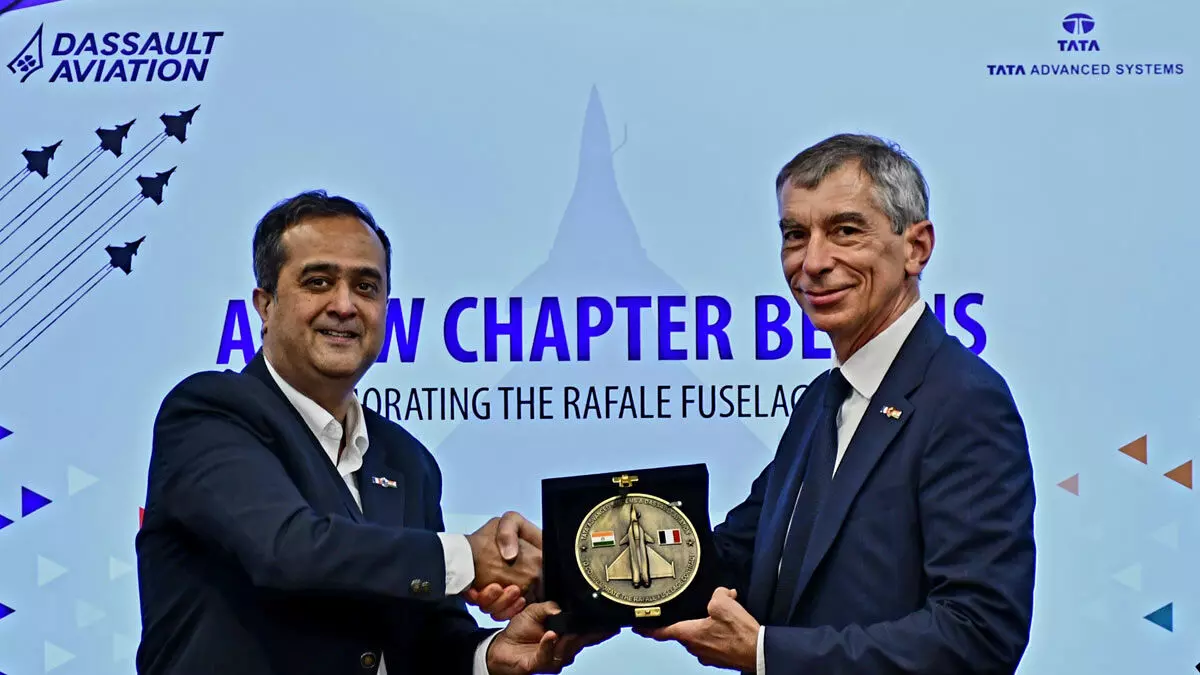

The recent signing of four Production Transfer Agreements between Dassault Aviation and Tata Advanced Systems Limited (TASL) marks a pivotal moment in India’s aerospace ambitions. For the first time, complete Rafale fighter aircraft fuselages will be manufactured outside France — and that too, in Hyderabad. It is more than a business deal; it is a powerful affirmation of India’s growing credibility in high-precision defence manufacturing and an important stride toward strategic autonomy. Under the agreement, TASL will manufacture key structural components of the Rafale fighter jet, including the front, central, and rear fuselage sections, in a new, state-of-the-art facility in Hyderabad. The facility is expected to begin delivering fuselage sections by FY2028, eventually ramping up to producing up to two complete fuselages per month. While India’s acquisition of Rafale jets has long been a topic of political and strategic discourse, this manufacturing partnership shifts the narrative from procurement to production — from dependence to participation. For Dassault Aviation to transfer the production of the Rafale’s core fuselage components — a critical part of any fighter aircraft’s structure — to India speaks volumes about India’s emergence as a reliable industrial partner in global defence supply chains. The Rafale is a fourth-generation multirole fighter, and its fuselage demands high levels of precision, quality assurance, and technological sophistication. The fact that this responsibility has been entrusted to TASL reflects the competence and credibility India’s private aerospace players have earned over the last decade. This move also underscores the gradual, but steady, realisation of the “Make in India” and AtmaNirbhar Bharat visions. For years, India’s defence procurement has been plagued by import dependency. Over 60 per cent of India’s defence needs are still met by foreign suppliers, which creates strategic vulnerabilities, especially in times of global disruption. Shifting from being a buyer to becoming a builder is not a semantic shift — it is a transformative one. Indigenous production of key aircraft components, such as the Rafale fuselage, helps India gain mastery over critical manufacturing processes, reduces long-term costs, and provides an impetus to the local aerospace ecosystem. The significance of this development is multifaceted. First, it demonstrates the success of India’s private sector in carving a niche in a domain traditionally dominated by the public sector. TASL, in collaboration with global defence majors like Lockheed Martin and Boeing in the past, has consistently proven its capability to deliver aerospace components with world-class precision. With this new partnership, Tata moves a notch higher — from component manufacture to structural integration — bringing India a step closer to full-spectrum aircraft manufacturing. Second, the Rafale fuselage project will help deepen India’s aerospace supply chain. The ripple effects of this investment will touch a range of ancillary industries — machining, metallurgy, composite materials, avionics support, quality certification, and more. SMEs will find new opportunities to participate in the global defence market, enhancing job creation, innovation, and technical upskilling across the board. Third, it positions India more assertively on the global map as a defence manufacturing hub. As geopolitical tensions rise and countries look to diversify their supply chains, India’s growing capabilities in producing complex defence platforms could make it a preferred destination for both co-production and exports. If successful, the Hyderabad facility could become a model for future aircraft programs, including unmanned aerial systems, helicopters, and even fifth-generation fighter jets. However, this milestone also brings with it important responsibilities. The production of a complete Rafale fuselage is a high-stakes venture that requires a sustained commitment to quality, precision, and delivery timelines. Any lapse could dent not only the Tata-Dassault relationship but also India’s broader defence manufacturing credibility. It is imperative that the regulatory, infrastructural, and policy support systems are streamlined to facilitate smooth execution. Delays in land acquisition, approvals, or supply chain disruptions must be avoided at all costs. It also offers a timely opportunity to revisit the balance between public and private sector roles in defence production. While HAL and DRDO continue to be indispensable in India’s indigenous defence ecosystem, the private sector’s agility, risk appetite, and global exposure make it a necessary engine for growth. The Rafale fuselage project is a strong case study of how India can harness public-private synergies, with the government playing the role of enabler and regulator, rather than sole executor. Strategically, the fuselage manufacturing move also strengthens India’s position vis-à-vis France. As traditional allies, India and France have deepened ties in defence, nuclear energy, space, and climate action. This partnership gives their strategic relationship a sharper industrial edge. In the long run, such projects could serve as templates for similar co-production efforts in space technologies, unmanned platforms, and even marine defence systems. Yet, amid the applause, it is important to acknowledge the long road ahead. True AtmaNirbharta in aerospace is not achieved by assembling parts alone. It requires a deep pool of skilled technicians, indigenous design capabilities, robust research and development, and self-sufficiency in critical subsystems like engines and radar. India still imports jet engines, radar systems, and advanced avionics — the brain and heart of combat aircraft. The next phase must address these gaps with equal seriousness. The Rafale fuselage production in India is more than a manufacturing win — it is a leap of faith, capability, and strategic direction.