Axe on the Root?

Opposition parties and the Chief Election Commissioner, Gyanesh Kumar, are engaged in a fiery battle of words over transparency and independence in the conduct of India’s top constitutional poll body. Criticism and questioning form the bedrock of democratic governance, but what is unfolding between opposition parties and the CEC is beyond criticism. It bears the semblance of a bitter animosity that is loaded by prejudices on both sides of the spectrum. The narrative of the Election Commission of India being on the side of the government — whether true or not — has cast a shadow on the credibility of the Indian democracy in function. At stake is something as vital and fundamental as people’s right to vote. For instance, Bihar’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR), especially the rush with which it is being carried out, has raised disturbing questions and a burning controversy. Critics — and there is no dearth of them — have alleged that the EC is working at the behest of the ruling NDA to recompose the electoral roll in a partisan and unfair manner. The ambiguities of the allegations, as well as their defence, are so profound that the Supreme Court had to intervene in the matter.

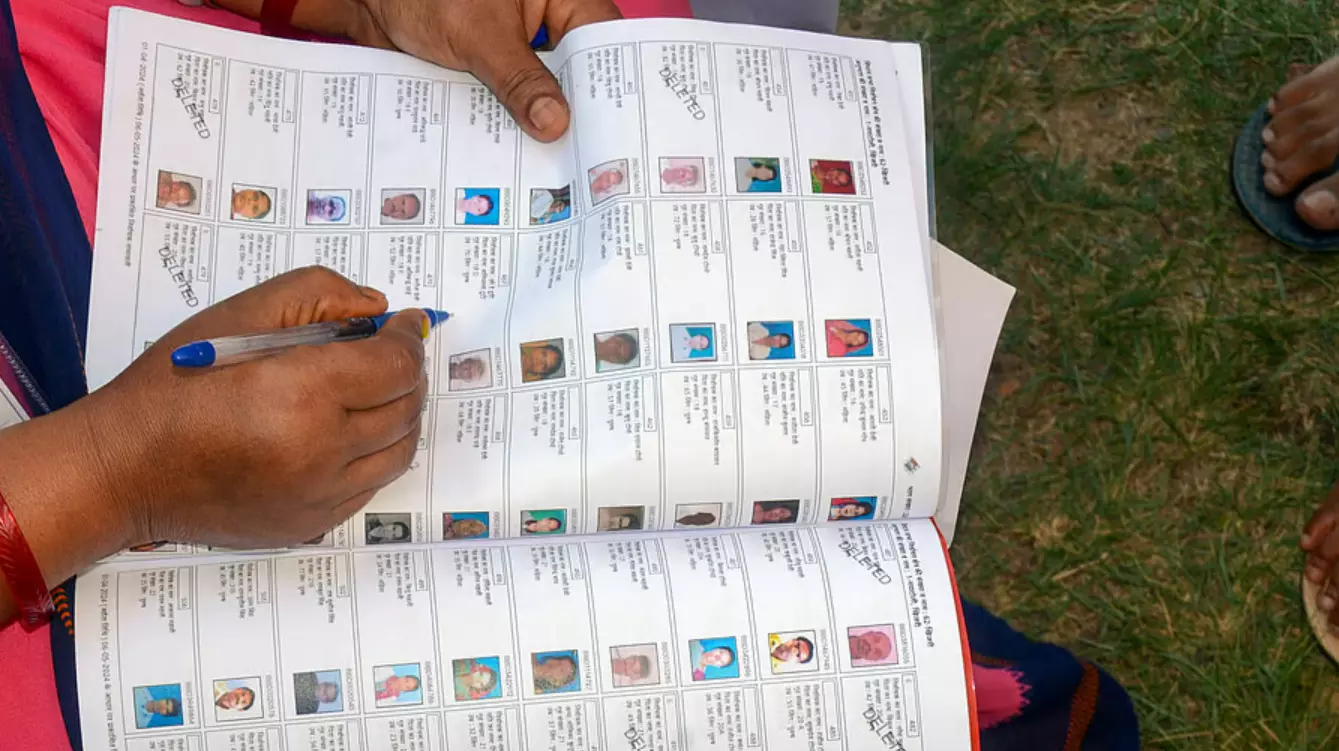

On August 14, the Court ordered the Election Commission of India (ECI) to publish details of 65 lakh names deleted from Bihar’s draft electoral roll along with reasons for their exclusion. The fact that such a basic principle of natural justice — telling citizens why their names were struck off the rolls — required judicial compulsion indeed reflects poorly on the ECI’s commitment to fairness and transparency. Citizens logging on to the ECI’s voter portal now find machine-readable lists of deletions, searchable by EPIC number or booth. However, this belated transparency only came after the Court stepped in. Left to its own devices, the Commission seemed content to leave voters in the dark, as if disenfranchisement was casual and not a grave violation of citizens' fundamental rights. Certain reports suggest that close to 32 lakh women have been removed compared to 25 lakh men, despite higher male migration and mortality rates. If validated, this systemic dysfunction has the potential to disenfranchise many, particularly the most vulnerable: women, Dalits, migrant labourers, daily wagers, and small farmers. For many, producing legacy documents from 2003 is an impossible ask. Forcing such burdens is tantamount to a citizenship test masquerading as an electoral revision. The ECI has argued that voters in the draft roll were vetted by Electoral Registration Officers against 11 “indicative documents.” Yet it has consistently resisted the Court’s repeated nudges to include the Aadhaar card, India’s most widely available identity proof.

Transparency remains another Achilles’ heel. Instead of consolidating the deletion lists and reasons in a single public database, the Commission has scattered them across portals and PDFs, making scrutiny by civil society or journalists a cumbersome exercise. Moreover, despite the Court’s explicit directive to publicise the deletions in newspapers, television, and social media, there has been no sign of such outreach. For a poor migrant worker who does not trawl government websites, the absence of physical notices and vernacular publicity might mean disenfranchisement will likely go unchallenged.

At the heart of this controversy lies a constitutional dilemma. Article 324 grants the ECI plenary powers over elections. But those powers cannot be weaponised against the very people they are meant to serve. The Court has rightly underlined that while it will not usurp the Commission’s mandate, the manner of exercise of power must remain “reasonable” and provide “comfort to citizens.” That reminder is essential. In Bihar today, in other states tomorrow, the SIR will shape who gets to vote. A flawed process sets a dangerous precedent for the rest of the country. The integrity of India’s democracy rests not merely on the holding of elections but on the inclusivity of its voter rolls. By forcing the Commission to open its books, the Supreme Court has drawn red lines that must endure. India’s democracy deserves better than a Commission that treats transparency as an inconvenience and voters as expendable. Electoral rolls are not statistics to be trimmed—they are the beating heart of the republic. The Supreme Court’s take on the broader aspects of the case, to be revealed in the coming hearings, is something every Indian’s eyes are hinged upon. Do no wrong. They are watching.