An uncompromisable entitlement

Education and health are two primary pillars of national as well as individual development. A rapidly growing India has become increasingly aware of the priorities it should set for progress. Families across India, irrespective of the wealth and income they hold, are more than willing to spend on education. The demand for ‘quality education’ is simply too high across India. Quality education, in turn, has come to be associated with the ‘English medium’ tag, especially in the northern belt. As is the norm, demand drives the cost upward. However, one must be extremely cautious while treating ‘education’ as a commodity in a market economy. Commodification of education could have disastrous consequences. Unfortunately, the undesirable trend is already underway across the length and breadth of India.

In a recent incident that has kept the Internet engaged over the past couple of days, a Jaipur-based professional, Rishab Jain, gave a breakdown of the annual costs for a Class 1 student, totalling a staggering Rs 4,27,000. Jain gave his own analysis as to how even a family earning 20 lakhs per annum will struggle to pay for this—a conclusion that some people over the Internet felt is exaggerated. Those debates notwithstanding, the cost of education has indeed gone exorbitantly high—prompting critical questions that pertain not just to the economic aspect but also constitutional. Back in 2002, Parliament passed the 86th Constitutional amendment, adding Article 21-A to the Constitution of India. The amendment made education a fundamental right for children aged between the ages of 6 and 14. Now that exorbitant prices are being charged across India in lieu of providing quality education, the question of affordability creeps in.

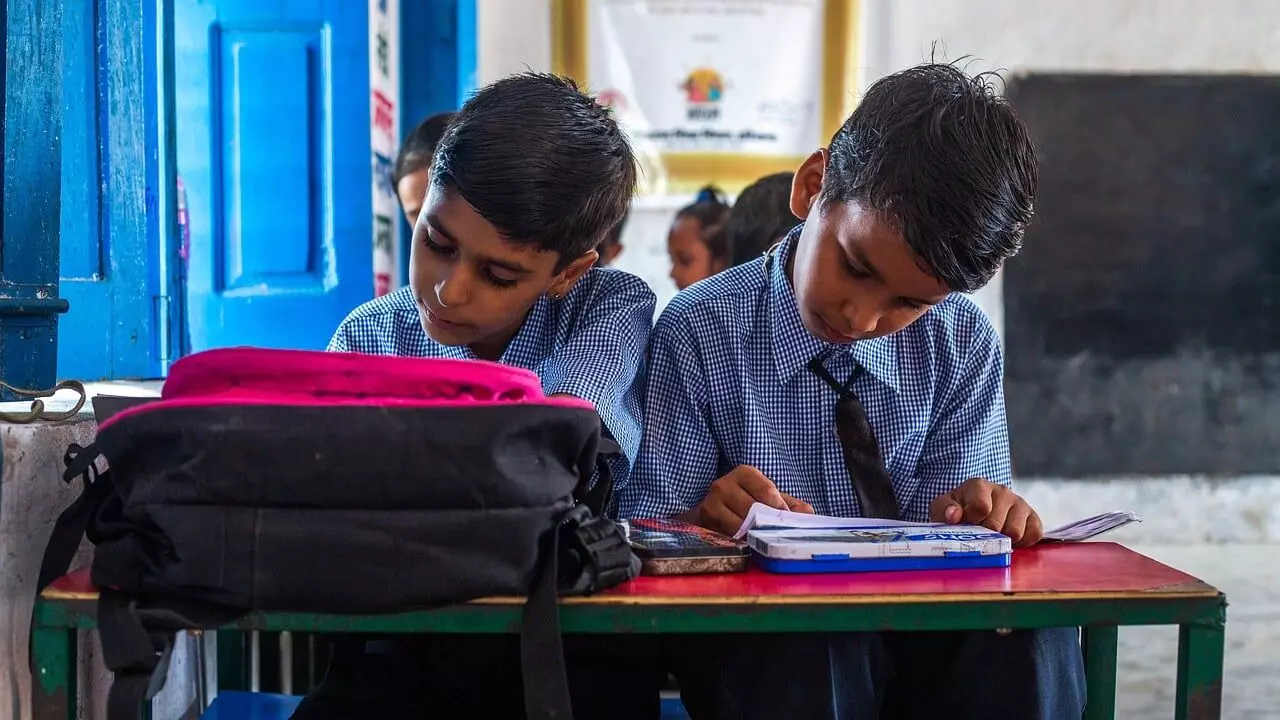

One may argue that public schools adhere to the tenets of the right to free education. However, this line of argument is very feeble. While technically they can be said to be upholding the fundamental right to free education, in practice, it is well known they have failed miserably. Barring in few states and union territories, the quality of education imparted in public schools is below par. Unless and until the state governments take proactive steps to provide affordable, quality education in public schools, the materialisation of the right to education as a fundamental right will be a faraway reality. It is a grim perception, as well as a reality, that there are two separate schooling systems for the rich and the poor in the country. This gulf creates unequal opportunities for two sections of society, which contradicts the principle ‘equality of opportunity’ enshrined in the Preamble of the Indian Constitution.

Some would also like to argue that not all private schools are so costly, and that there is a gradient of sorts, catering to people of different socio-economic status. This argument is heavily flawed. In the first place, the existence of gradience in a subject as critical as education is, in itself, a sign of inequality. Secondly, the mushrooming of substandard private schools, with ill-qualified teachers and inappropriate infrastructure, catering to a large section of lower middle class families, is a problem rather than a solution. Villages in northern India, as also in other parts of the country, are replete with good-for-nothing private, English medium schools. These schools often charge high costs from parents—most of whom don’t have required knowledge and time to assess what is being taught in the school in which their children study at the cost of their hard-earned incomes. The clusters of quality education are still very limited in India, and their number may not be good enough to cater to the needs of a vast student-age population in the country. The state governments must make education an affordable necessity, and not a luxury that only few can afford. More importantly, it should also exercise checks on those schools that charge disproportionately high fees.