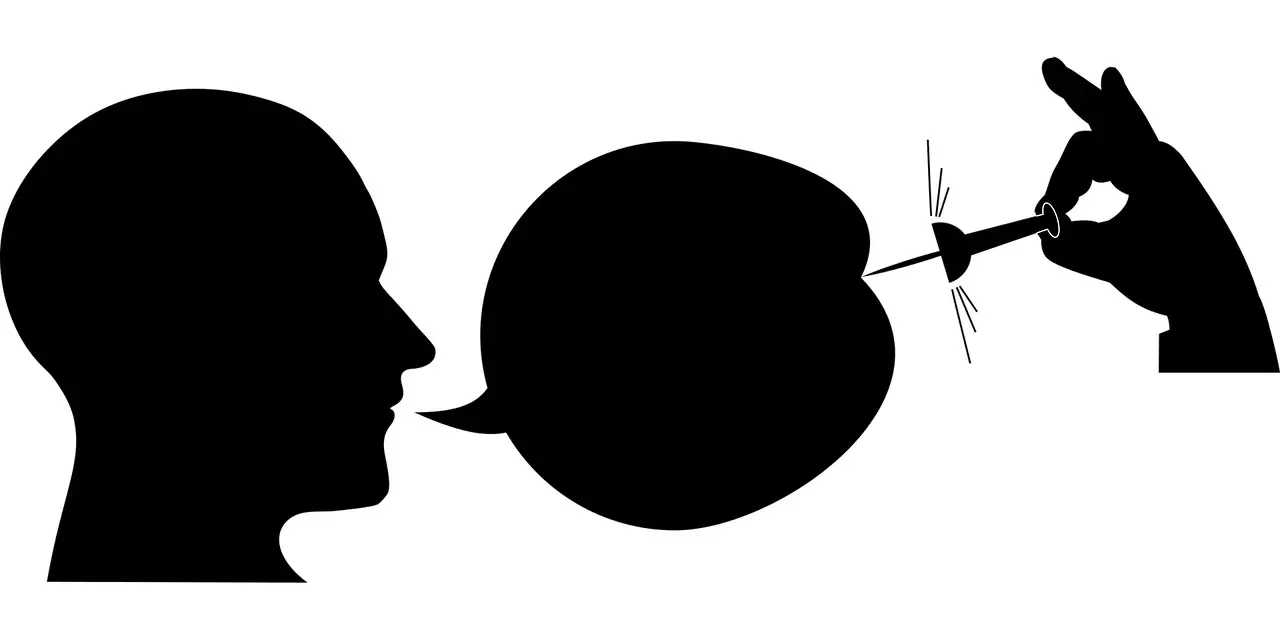

A regressive move

The recommendations submitted by the 22nd Law Commission to the law ministry have spun the wheels of justice in a regressive direction. Back in 2018 when the 21st Law Commission, while pointing out that every irresponsible exercise of the right to free speech and expression did not amount to sedition, sought public view, there was hope that the ‘draconian’ law may be diluted or eliminated. However, the recommendations made by the 22nd Law Commission appear to have dashed those hopes. One of the recommendations seeks to incorporate the Supreme Court’s judgement in Kedar Nath Singh vs State of Bihar which classified seditious act as something that leads to, or tends to lead to, violence or public disorder. Essentially, this incorporation could lead to incrimination of an individual based on her/his intent behind the action rather than on the outcome of the action. This might be a serious regression, making the sedition law more stringent than it currently is. It is also in contravention with certain Supreme Court rulings which have clarified that mere words and slogans against the state do not amount to sedition. The apex court has time and again questioned the validity and relevance of the law in present times. In a landmark judgement passed on May 11, the court had put the Sedition law on hold till the Central government carried out its review around the law. The governments — both Central and state — were barred from registering fresh cases of sedition. The recommendations put forth by the Law Commission — while the provisions of the law are still under abeyance and several constitutional challenges are pending before the Supreme Court — carries a semblance of legal contradiction. Amidst the increasing public discontent and anger among journalists, civil society organisations and the broader public, the commission has also recommended to increase the scope of punishment from three years to seven years, depending on the seriousness of the crime. The sedition law in India, Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), was enacted during the British colonial era to suppress dissent against British rule. Unfortunately, the law has continued to be applied even after India gained independence in 1947. Over the years, Section 124A has been criticized for its vagueness and misuse, leading to instances where citizens have faced criminal charges merely for expressing critical opinions against the government. It is this ambiguity which leads to stifling of dissent and criticism — advertently or inadvertently. The expectation from the 22nd Law Commission was that it would chalk out a solution to this ambiguity. But the commission’s report falls way short of doing any such thing. On the contrary, it appears to provide a license to the governments to go more freely about (mis)using the sedition law. According to a database created by Article 14, the number of sedition cases had increased by 28 per cent between 2014 and 2022. Human Rights Watch reported that since 2014, Indian authorities have filed more than 500 sedition cases involving more than 7,000 people. While the slapping of sedition charges has increased, the conviction rate remains abysmal — making the process itself a punishment. The nature of sedition cases covers a wide range, with certain cases bordering on trivialism and comical. There have been incidents when students were forced to spend months in jail for celebrating Pakistan’s victory over India in a cricket match. Quite clearly, the law holds potential to legitimise the increasing intolerance in Indian society. For journalists and media persons, it has been an eternal chain of repression. It is certainly not without reasons that Mahatma Gandhi described the Sedition law as the “prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Code designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen.” Furthermore, the law is in defiance with Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which states that restrictions on expression must be narrowly drawn on principles of necessity and proportionality to curtail speech as little as possible. India is among the last of democratic nations that still bank upon such a draconian law to protect their ‘national integrity’ and maintain ‘public order.’ The world has advanced much further and an aspiring nation like India cannot afford to lag behind. The recommendations of the Law Commission require a revisit.