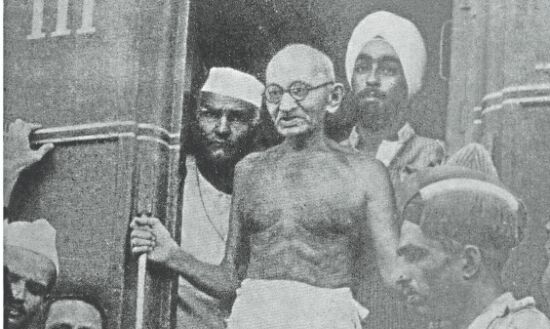

"Making of a Hindu Patriot" | Religious awakening

The book tells the story of the evolution of Hind Swaraj as a text of religious patriotism and of Gandhiji as the greatest Hindu Patriot, Deshbhakta Mahatma, of our times; Excerpts:

Author: J.K. Bajaj and M.D. Srinivas

Publisher: Haranand Books

Gandhiji’s Hind Swaraj is grounded in Dharma, which is often but inadequately translated as religion. The purpose of the text is to establish Dharma as the measure of civilisation and to restore it as the principle governing interactions between people and nations. The strongest condemnation of modern civilisation the text offers is that (HS 3:44): “This civilisation is irreligion, and it has taken such a hold on the people of Europe that those who are in it appear to be halfmad.” The greatest worry about the ‘Condition of India’ it expresses is that (HS 3:48): “…India is becoming irreligious. …We are turning away from God.” And, the ideal solution of the conflict between the British rulers and the Indian subjects it presents is that the relationship between the ruler and the ruled be anchored in Dharma. Hind Swaraj does not ask the English to leave India, but to remain and rule in accordance with Dharma. If they were to agree to rule in such a manner, it would be for the good of all: “So doing, we shall benefit each other and the world. But that will happen only when the root of our relationship is sunk in a religious soil.” (HS 3:97.)

FORMATIVE INFLUENCES

Childhood Impressions

Given the central place that Dharma occupies in Hind Swaraj, we begin this collection of extracts on the background of Hind Swaraj with several extracts from Gandhiji’s Autobiography that describe the evolution of his religious consciousness. In the very first chapter of the Autobiography from which we have taken the first extract (A-1), he describes the deep impression made upon him by the disciplined and austere way of life—anchored in an earthly and empathetic commonsense—of his mother, which indeed epitomises the saintliness of the ways of an ordinary religious Hindu. This is the religion that Gandhiji imbibed and made his own; his Hind Swaraj can indeed be read as an effort to raise this disciplined austerity of a religious Hindu beyond the personal sphere and make it the basis of social and political life of nations.

In the second extract in this collection, A-2, Gandhiji describes the various manifestations of religious living around him that he was exposed to during the formative years at school. Here again, what he remembers as the most important influences are the simple faiths, beliefs and scriptural encounters of the ordinary Hindu: The Ramanama learnt from the maid, Rambha; the Ramayana recitals of a saintly person, Ladha Maharaj; the story of Ladha Maharaj curing himself of leprosy through the application of bilva leaves that had been previously offered to Shiva and the repetition of Ramanama; the occasional public readings of Bhagavata; and so on. These and similar experiences used to be part of growing up in the small towns and villages of India until recently. Unfortunately, much of that simple religiosity of ordinary Indian living has been lost.

In this extract, Gandhiji also describes the spirit of tolerance of diverse religious beliefs that pervaded his home and his town. Even so, he seems to have developed, at that early age, a dislike for missionary activities aimed at swaying others from their Dharma and bringing them into another fold. Here, in A-2, he expresses this dislike in rather strong terms:

…many things combined to inculcate in me a toleration for all faiths. Only Christianity was at the time an exception. I developed a sort of dislike for it. And for a reason. In those days Christian missionaries used to stand in a corner near the high school and hold forth, pouring abuse on Hindus and their gods. I could not endure this. …About the same time, I heard of a well-known Hindu having been converted to Christianity. It was the talk of the town that, when he was baptized, he had to eat beef and drink liquor, that he also had to change his clothes, and that thenceforth he began to go about in European costume including a hat. These things got on my nerves.

Both the tolerance for diverse faiths and the dislike for proselytising of any kind, especially by the Christian missionaries, remained with him throughout his life.

Religious explorations

While in England as a student during 1888-1891, Gandhiji came in contact with Theosophists and several sects of Christians, mainly through his interactions with the Vegetarian Societies. Extract A-3 from this period describes his first introduction to theological literature in the company of a couple of Theosophist acquaintances. Such contacts continued and became more intense during his early years in South Africa, where he also came in contact with some deeply religious Muslims. These encounters forced him to begin seriously exploring his so far implicit religious faith and consciousness. Extracts A-4 to A-6 from his early years in South Africa describe his exploration into the religious literature of Christianity and his attempts to read the Koran. These extracts also describe how his study of Christianity and Islam, especially the former, led him to an intense study and comprehension of his own religion, Hinduism. Around this time (1894), he began to correspond with Shrimad Rajchandra—also known as Raychandbhai and sometimes referred to simply as Kavi, the Poet Philosopher—whom he adopted as his mentor in matters concerning religion.

Describing the context of these religious explorations of his, Gandhiji says (A-5):

As Christian friends were endeavouring to convert me, even so were Mussalman friends. Abdulla Sheth had kept on inducing me to study Islam, and of course he had always something to say regarding its beauty.

I expressed my difficulties in a letter to Raychandbhai. I also corresponded with other religious authorities in India and received answers from them. Raychandbhai’s letter somewhat pacified me. He asked me to be patient and to study Hinduism more deeply. One of his sentences was to this effect: ‘On a dispassionate view of the question I am convinced that no other religion has the subtle and profound thought of Hinduism, its vision of the soul, or its charity.’

By this time, Gandhiji seemed to have already determined that his life’s quest was for self-realisation, Moksha, and that he would fulfil this quest through the service of India. Extract A-6 from Religious Awakening his recollections of the period (1895-96) begins thus: “If I found myself entirely absorbed in the service of the community, the reason behind it was my desire for self-realisation. …I felt that God could be realised only through service. And service for me was the service of India…” Political and social activity for him thus became a form of Tapas, religious penance. This way of thinking found its fullest expression in Hind Swaraj, and in the concept and practice of Satyagraha.

Excerpted with permission from Making of a Hindu Patriot; published by Haranand Books