"Jallianwala Bagh" | On that frightful day

In a gripping piece of forensic exploration — Jallianwala Bagh — VN Datta cuts through the theories to reveal what really happened in Amritsar in 1919, and why; Excerpts:

Author: VN Datta

Publisher: Penguin

Before Dyer’s arrival, eight speakers, including Abdul Aziz, Dr Gurbax Rai and Rai Ram Singh, had spoken. A picture of Kitchlew had been displayed and it was said that his portrait presided. Brij Gopi Nath Bekal, a bank clerk, had recited his Urdu poem ‘Faryad’ which he had addressed to the government and from which the following couplet is taken:

Of the threat of being deprived of wings and feathers which you hold out to us. Let the season of spring visit our garden. The feathers will also come out with the appearance of buds.

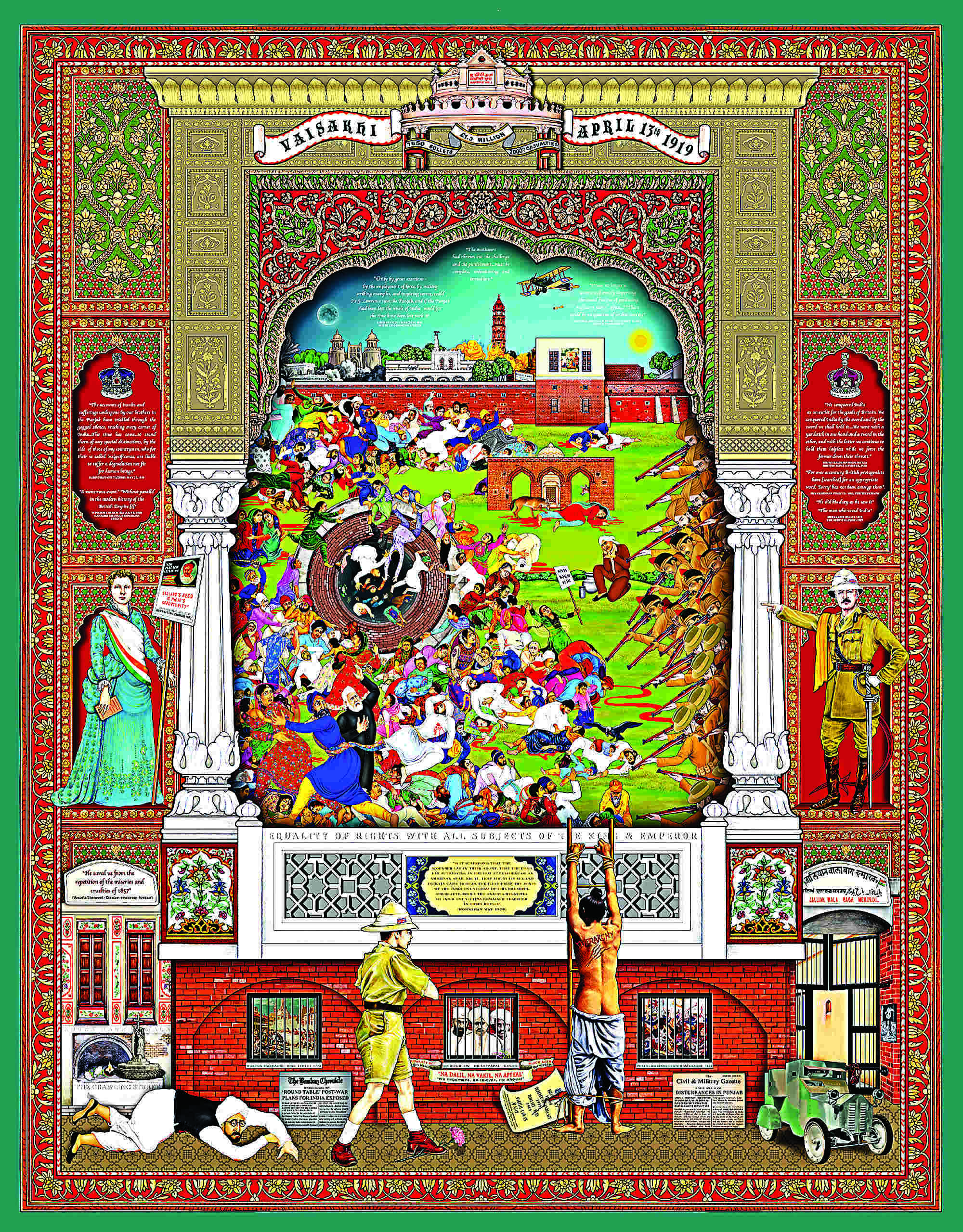

An aeroplane displaying a flag circled low over the Bagh at about 4 p.m. The people panicked and began to move away, but Hans Raj assured them that there was no cause for alarm. He remarked that the aeroplane was ‘doing its work and that we should continue our work [you do your own]’. The meeting had passed two resolutions, the first calling for the repeal of the Rowlatt Act and the second condemning the firing on 10 April and extending sympathy to the relatives of the dead. Durga Das Vaid, the editor of Waqt and a political worker, was moving a third resolution on the repressive policy of the government when the crowd saw armed soldiers standing behind them. The crowd shouted, ‘Aagaye, aagaye’ (They have come, they have come).

Dyer, standing on a raised platform inside the entrance, was struck by the diverse nature of the crowd. It was Baisakhi, a day which has special significance for the people of the Punjab, and as usual there was a large influx into the town of people from adjacent areas who had come for a dip in the holy tank surrounding the Golden Temple. The cattle market which was traditionally held on this day near Gobindgarh

Fort had also attracted customers from outside and quite a large number of villagers had found their way to the Bagh. Some people were lying on the ground relaxing with half an ear to what the speakers were saying, some were sleeping and others were squatting in groups playing cards.

Dyer saw the thickest crowd around the rostrum under the peepal tree about 150 yards away and the nearest groups within ten to twenty yards of him. It was approximately 5.15 p.m. and the sky was still overcast. The dust disturbed by the crowds in the Bagh hung over the area and added to the gloom. Within thirty seconds of his arrival, Dyer deployed his troops, the Gurkhas to the left and the Baluchis to the right of the entrance to the square. The ground on which the soldiers stood was at a higher level than the rest of the area—an advantageous position from which to fire on the crowd. When asked before the Hunter Committee what his first action was upon reaching Jallianwala Bagh, Dyer answered, ‘I opened fire.’ In his statement before the Army Council, he wrote, ‘Hesitation I felt would be dangerous and futile, and as soon as my fifty riflemen had deployed I ordered fire to be opened.’ Durga Das was speaking and gesticulating with his hands. Hans Raj intervened exhorting the crowd to sit down and not to panic. Immediately the troops were deployed, they opened fire but at first the crowd shouted back ‘Phokian’, ‘Phokian’, imagining that it was just a bluff. They quickly lost their illusions, however, as people began to crumple and fall.

The crowd’s reaction to the initial shock of the first volley was to stream away in great panic; but where could people go? Close to their left there were houses, further ahead the well, on their right the open space, and behind, the guns of the soldiers. They found themselves completely trapped. Each soldier was loading and firing. ‘The men did not hesitate to fire low and I saw no man firing high,’ said Captain Briggs. Many fell dead on the spot and many more, while falling, were crushed under the weight of others. Waves of men fell over each other and many died of suffocation. Some turned towards the samadh and took cover there but successive volleys pulled them down. A large number of people flung themselves down from the rostrum, others rushed towards the exits and others still tried to climb the mud-and-brick wall, but most of them were mown down by a hail of bullets. A few men managed to hoist

themselves on to the wall but they fell down helplessly on the other side. Girdhari Lal, who saw the scene closely, described it in grim detail:

I saw hundreds of persons killed on the spot. The worst part of the whole thing was that firing was directed towards the gates through which people were running out. There were small outlets, 4 or 5 in all, and bullets actually rained over the people at all these gates . . . and many got trampled under the feet of rushing crowds and thus lost their lives . . . Blood was pouring in profusion . . . even those who lay flat on the ground were shot . . . some had their heads cut open, others had eyes shot and their nose, chest, arms and legs shattered.

People were even wounded on the second and third storeys of the houses abutting the Bagh. Mian Raizul Hasan, a resident of one of them, remarked, ‘A bullet struck my roof.’ Inside the Bagh, everyone was for himself, pushing and heaving, kicking and scratching in the frantic effort to escape. People continued to fall like flies and heaps of bodies began to pile up under the walls and before the narrow exits. But still the shooting continued unabated and the troops were even ordered to concentrate their fire on the masses that had collected at these exits. The carnage increased tenfold.

When the firing ceased, there was not a corner left in the garden where people were not lying dead in large numbers. Even outside the Bagh, there was a heap of dead bodies. Khushal Singh, a resident of the Jallianwala Bagh area, notes, ‘In one gali there were fifty dead. Navi gali, close to the entrance near the Sultanwind gate, was full of dead people.’ In his statement on 25 August 1919 to the general staff, Dyer stated, ‘I fired and continued to fire until the crowd dispersed.’ The mob gradually disappeared. Those who ran knew not where they were running to because of the great terror that possessed them. Dazed and fear-stricken, Rattan Chand Kapur, a young man, ran fast for a mile and a half without realizing that he had done so. The firing continued for ten minutes and in that time 1650 rounds of 303 Mark VI ammunition were fired. There were two pauses of about a minute each during the shooting when Dyer surveyed the scene before him. When it was finally over, the Bagh looked like a battlefield. Corpses lay everywhere in great heaps and the wounded in their hundreds were crying out for water. The troops, having been given the order to cease fire, marched off the way they had come.

At 10 p.m. Dyer, accompanied by a small force, visited his pickets and marched through the city in order to make sure that his curfew orders were being obeyed. The city was absolutely quiet: not a soul was to be seen on the roads. At the Bagh, a few shocked survivors had remained to turn over the heaps of dead bodies in a desperate search for friends and relations. Lala Nathu Ram found the body of his brother under three or four others quite near the raised ground from which the soldiers had fired, but many left not knowing the fate of their kin because they were afraid of being fired upon again after 8 p.m. Those who remained were joined by Attar Kaur and Rattan Devi. Attar Kaur found her husband Bhag Mal Bhatia’s dead body and boldly took it home with the help of another person.

Excerpted with permission from Jallianwala Bagh by VN Datta; published by Penguin