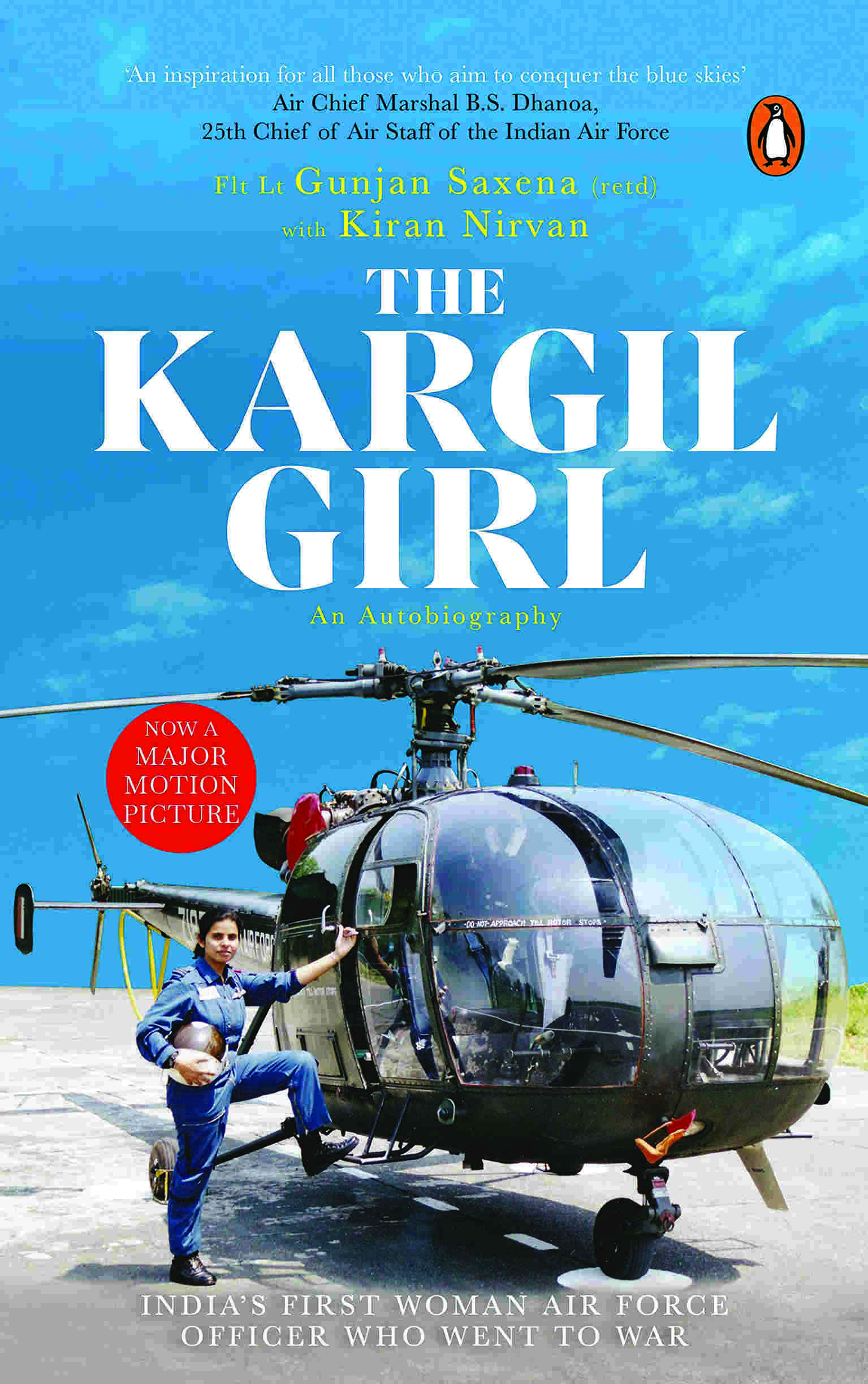

"The Kargil Girl: An autobiography" | Into the horizon

From airdropping vital supplies to Indian troops in the Dras and Batalik regions and casualty evacuation from the midst of the ongoing battle, to meticulously informing about enemy positions, Gunjan Saxena fearlessly discharges her duties, earning herself the moniker The Kargil Girl. This is her inspiring story, in her words; Excerpts:

Author: Flt Lt Gunjan Saxena (retd) and Kiran Nirvan

Publisher: Penguin

More than a week of tragic losses, confirmed gains and increasing tensions later, I was still flying between Kargil and Srinagar almost regularly. There was hardly any time for me to think about and realize that I was taking part in a war in the very first tenure of my service. But the second week of June was a tad less busy for me and no sorties were planned for two days straight. It was the tenth day of June, a dull and quiet day at the Srinagar airbase. Two of our four helicopters in Srinagar had gone back to Udhampur for servicing. But I was told to stay in Srinagar. The day started with the regular morning briefing, where I came to know about a fighter mission that would take place in the morning. Another thing that was being talked about by everyone was how Pakistan, as a ‘goodwill gesture’, had, on 3 June, released Flight Lieutenant K. Nachiketa, an Indian Air Force pilot taken as a prisoner of war by the Pakistan Army patrol on 27 May 1999, when his MiG-27 had crashed. But there was news of the handing over of mutilated bodies of six soldiers of a battalion of the JAT regiment. Where was goodwill or the spirit of soldiering in that? There were rumours everywhere about how Pakistan was treating captured soldiers. After hearing what they did to the six soldiers of the JAT regiment, officers and men of the Indian Air Force started discussing how it would be better to just shoot oneself rather than become a prisoner of war if their aircraft crashed into enemy territory. I would not deny that this thought crossed my mind that day. After all, I had been flying over captured hostile territory and the possibility of getting caught did exist. The rest of the day was spent in doing almost nothing. Sitting alone in a small room on a rather quiet afternoon, I began to imagine how I would put my INSAS rifle to use if I ever got caught. ‘Whatever happens, I will not let them capture me alive’ — I had somehow made a silent pact with myself somewhere in the back of my mind, even though I tried to shrug off any thoughts about it. Listening to the news on the radio about how France and the United States had acknowledged that Pakistan was responsible for crossing the LoC, I slipped into a deep slumber.

Have you ever travelled in a train for so long that when you finally get off at your destination, you can still feel the ground beneath your feet shaking the same way as on a moving train? A feeling similar to this made me wake up from my sleep, but it was not related to trains. I thought I heard muffled sounds of blasts and distant gunfire. When I got out of bed and walked outside, there was a strange silence on the airstrip. I had been hearing the sounds of blasts and gunfire so much on my regular visits to Kargil that I felt like I could hear them even in my sleep. It was a strange feeling. When inside the briefing room at Kargil or just flying over enemy bunkers, I could hear the muffled sounds of artillery bombardment only a few hundred metres from us, sounds of machine-gun fire echoing in the valleys or, at times, could see muzzle flashes in the rocky mountains, which would make me realize all over again that a bloody battle was underway somewhere in those mountains. But it all creeps into the subconscious even if no attention is paid to it. Sometimes I would be taking a nap inside the mess before a sortie, and suddenly the sound of mortar fire or artillery gunfire would wake me up. Sometimes these mortar rounds would go off so close to the airstrip that we could feel the windowpanes vibrating. But nothing mattered in that moment. The battle noise was not discomforting—it was the silence that was dreadful.

As I stood outside my room in the sunny afternoon, I could see that a wreath-laying ceremony was going on in a far corner of the airstrip. Men in army and air force uniforms slowly marched towards a row of coffins covered in tricolour carrying the mortal remains of martyred soldiers from the night before or that morning, and offered wreaths to the martyrs as the buglers played a tune. The battle had ended for these bravehearts. They would now be airlifted to their hometowns, where their grieving families awaited them for their last rites. I wondered in that moment if their families were even aware of this or whether they would be told later. I had never found the time to think about this before that day, even though I had been witnessing these ceremonies since I had come to Srinagar. War is surely a sad affair in the end. The enemy held defences at heights and was, therefore, at an advantage. And at the very beginning of the war, Indian troops were fighting in what appeared to be suicide missions, as the army had not yet achieved a considerable build-up of forces. But then it reminded me of Papaji’s words, who always considered martyrdom a privilege. There was no better way to die, he would say, and that all of us should be proud of them. Only the most fortunate get to live and die as heroes; only the most fortunate get to be wrapped in tricolour. No ordinary man could earn it.

I felt respect and grief for the martyrs at the same time as I stood witness to the wreath-laying ceremony from a distance. I closed my eyes and paid homage to all those who had laid down their lives for their nation since the Kargil War had begun.

Since 6 June 1999, the army had achieved a sufficient build-up of troops and the logistics to launch major offences in the Dras and Kargil sectors. The war was only going to intensify in the coming days. And it would be accompanied by strategic air strikes, since the aim was to keep the Srinagar–Leh highway free of enemy threat. One such air strike was carried out earlier that day. As I stood there lost in my thoughts, our flight commander, Wing Commander Srivastav, came running towards me.

‘Good afternoon, Sir,’ I saluted him.

He saluted back as he stopped in front of me, catching his breath. ‘We need to hurry up,’ he said. ‘We need to get airborne immediately.’

(Excerpted with permission from ‘The Kargil Girl: An autobiography’ published by Penguin Random House)