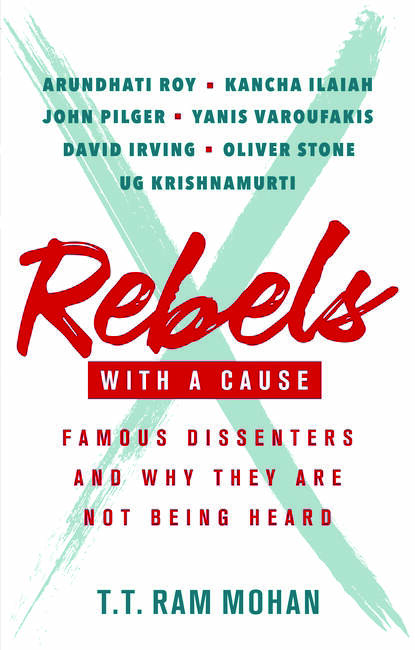

"Rebels with a Cause" | India’s irrepressible gadfly

Prof. TT Ram Mohan profiles well-known dissenters Arundhati Roy, Oliver Stone, Kancha Ilaiah, and others to illustrate how, in practice, dissent tends to be severely circumscribed — Rebels with a Cause is a book that asks hard questions to challenge the way we view, and live in, the world – an important book for anyone who refuses to accept the status quo; Excerpts:

Author: TT Ram Mohan

Publisher: Penguin

In early 2014, Arundhati Roy wrote a lengthy introduction to one of B.R. Ambedkar’s most powerful works, Annihilation of Caste, published by Navayana, a publishing house in New Delhi. The introduction is not just about the book or even about Ambedkar. A large portion of it is devoted to Gandhi. The Gandhi that Roy portrays is not the champion of the oppressed that we know. He is a spokesman for the ‘haves’ in society, whether in South Africa or in India. Roy’s essay takes Gandhi down a peg or two.

Much as Roy admires Ambedkar, she doesn’t spare him either. She suggests his views on Adivasis are as patronizing as Gandhi’s on Untouchables. She says Ambedkar saw Adivasis as backward, even savage. The Indian Constitution, of which Ambedkar was the author, allowed the Indian state to appropriate Adivasi homelands, reducing Adivasis to ‘squatters on their own land’.

The book set off a storm. Rajmohan Gandhi, a historian and Gandhi’s grandson, said the chief purpose of the book was neither an exploration of the thesis of Annihilation nor the Gandhi–Ambedkar relationship. Its ‘true aim’ was the demolition of Gandhi. Dalits criticized Roy for much the same reasons. Some even saw the introduction as an exercise in blatant self-promotion.

Roy’s introduction had, however, served the publisher’s purpose. The controversy brought Annihilation a degree of attention it had not received before. The book was extensively reviewed and commented upon. Roy was invited to Columbia University to talk about it. There was a book launch in London. Roy was interviewed widely. The publisher’s instinct that Roy’s anti-establishment status and her rousing, polemical style would work wonders for Ambedkar’s book had been proved right. Ambedkar’s assault on Hinduism had finally got the audience it deserved.

Arundhati Roy is the quintessential gadfly. She is nothing if not controversial. She is forever taking on the establishment, siding with the underdog. The Indian government, the Indian judiciary, the United States, Israel, large corporates, the mainstream media, Mahatma Gandhi, Narendra Modi—all these and others have earned her scorn. Roy wants to set the whole world right.

When you make so many enemies, it’s hard to survive. Roy’s international stature has spared her the crippling costs that often go with denouncing the high and mighty. But for her celebrity status, she may well have been trampled over long back, perhaps languished in obscurity in an Indian jail.

Roy shot into prominence in 1997 when her novel, The God of Small Things, won the Booker Prize and went on to become a bestseller. Roy is said to have received an advance of half a million pounds. The book was translated into some forty languages and sold over 6 million copies.

Most writers would have capitalized on the spectacular success of a first work by churning out more fiction. Roy did not for a long, long time. Her second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, was released only in May 2017 and became an instant bestseller.

In the intervening two decades, Roy instead used her celebrity status and her skills as a writer to fight injustice and oppression in various forms. In the process, she has become a public intellectual and social activist. She has written articles, essays and books; given numerous interviews and speeches; taken part in demonstrations and courted arrest.

Roy has taken up all manner of causes. She has joined hands with Medha Patkar, another well-known social activist, in opposing the Sardar Sarovar Project (SSP) for setting up a dam on the river Narmada. She has been an advocate of Kashmiri separatism. She championed the case of Afzal Guru, a Kashmiri who was convicted and hanged for his involvement in the attack on India’s Parliament in 2001.

Roy has shown solidarity with the revolt in the forest belts of the state of Chhattisgarh and elsewhere. She rejects the characterization of the insurgents as ‘Maoists’. She sees the insurgency as a struggle of the poor against corporate exploitation, aided and abetted by a mendacious state. She has lashed out against American foreign policy, Israel’s policy towards Palestinians, and the killing of civilians by the Sri Lankan government in its war against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). She has railed against Narendra Modi and the Hindu Right.

Roy’s writings and comments have got her into trouble with India’s courts. In March 2002, she spent a day in jail and had to pay a fine of Rs 2000 after being convicted for contempt of India’s Supreme Court. The court held that some comments Roy had made in an affidavit she had filed in connection with the SSP amounted to lowering the dignity of the court. In December 2015, Roy had another brush with the courts. The Bombay High Court issued a contempt notice to Roy for remarks she had made in connection with a case the high court was dealing with. In July 2017, the Supreme Court issued a stay on the proceedings.

At times, Roy’s positions, while contrarian, have seemed persuasive. Roy was critical of the anti-corruption campaign of another social activist, Anna Hazare. The campaign had received enormous publicity in the media and roused the Indian middle classes for a while. Roy was not impressed by Hazare. She faulted the campaign for focusing entirely on corruption in government while ignoring corruption in the private sector. Corruption, Roy argued, was merely the symptom of a deeper problem, namely, a deeply unequal society.

At other times, her positions have seemed eccentric. In November 2008, there were terrorist attacks in Mumbai. These are widely believed to have been orchestrated by the Pakistani establishment and drew universal condemnation. Roy angered many by arguing that these attacks should be viewed in the wider context of events such as the Partition of India, the killing of Muslims in the 2002 Gujarat riots and the Kashmir conflict. All the events that Roy mentions may have inflamed passions in Pakistan. But do they justify Pakistan-sponsored attacks on civilians in India?

If there’s a common thread to these seemingly unrelated causes, it is opposition to the establishment. Roy’s problem is not this or that policy, event or political party. Her problem is the existing order, whether in India or in the world at large. She sees the order as fundamentally iniquitous. She believes, as the Naxalites do, that the problems in the present order cannot be remedied from within the system. The system has to be overthrown. What is to take its place is not clear, though.

It’s been quite a journey for Roy. She was born in Shillong in the state of Meghalaya to a Bengali Hindu father, Ranjit Roy, and a Malayali Syrian Christian mother, Mary. Mary happened to be a secretary at Metal Box, at the time a prominent British-promoted company based in Calcutta. She met her future husband through his brother (father of Prannoy Roy, the well-known media personality and founder of the TV channel, NDTV) who was also at Metal Box.

On her wedding night, Mary found out that her husband was an alcoholic. When Roy was two years old, her parents separated. (They never got divorced.) Her mother went with Roy and her brother to a cottage in Ooty that belonged to her mother’s family. Two years later, the children moved with their mother to Kottayam in Kerala where her mother had been invited to start a school by the Rotary Club. On land given by the club, Mary opened her school, Corpus Christi, with seven students (including her two children). Within a year, she had added forty students. Today, it has come to be known in the town as an ‘elitist’ school.

Mary became well known in Kerala when she filed a public interest litigation case challenging the Syrian Christian inheritance law under which a woman could inherit only one-fourth of her father’s property or Rs 5,000, whichever was less. The Supreme Court ruled that women could claim equal inheritance with retrospective effect from 1956. Roy seems to have inherited her mother’s fierce independence and spirit of rebellion. She has said, ‘Growing up in a little village in Kerala was a nightmare for me. All I wanted to do was escape’.

And escape she did. Roy went to the Lawrence School at Lovedale in the hill station Ooty in Tamil Nadu. She then studied at the School of Planning and Architecture, Delhi. There she met an architect with whom she lived together in Delhi and Goa until their relationship broke up. She returned to Delhi to join the National Institute of Urban Affairs. In 1984 she met a film-maker, Pradip Krishen, who introduced her to the film industry. The years that followed were quite uneventful. She worked for television and films. A screenplay she wrote for a movie, directed by her husband, In Which Annie Gives It those Ones (1989), won the National Film Award for Best Screenplay.

Then, The God of Small Things happened. The novel won the Booker Prize for Fiction. It brought Roy instant fame and wealth. Thereafter, she plunged headlong into a life of political activism.

In May 1936, B.R. Ambedkar was invited to deliver the presidential address at a conference organized by the Jat-Pat Todak Mandal (Forum for the Break-up of Caste), a Hindu reformist organization in Lahore. When the Mandal received the text of Ambedkar’s address, it found that there were parts that the Hindu community would find offensive. The Mandal advised Ambedkar to delete those parts. Ambedkar refused to oblige and the lecture was cancelled. Ambedkar then proceeded to print 1,500 copies of the lecture at his own expense. It was titled Annihilation of Caste.

(Excerpted with permission from TT Ram Mohan’s Rebels with a Cause; published by Penguin Random House)