‘James Bond of Bengal’ reminisces risking his life to capture covert images of Pakistan military activities

Jalpaiguri: Somnath Chowdhury’s life hung on a thread as he went about his job as a secret photographer for the Mukti Bahini (Bangladesh Liberation Army) during the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. In order to escape the vigilant eyes of the Pakistani Army, Chowdhury, now 78, concealed his sacred thread inside an amulet and disguised himself, risking his life to capture thousands of covert images of Pakistani military activities in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). These photographs were smuggled to the Indian Army, providing vital intelligence during the war.

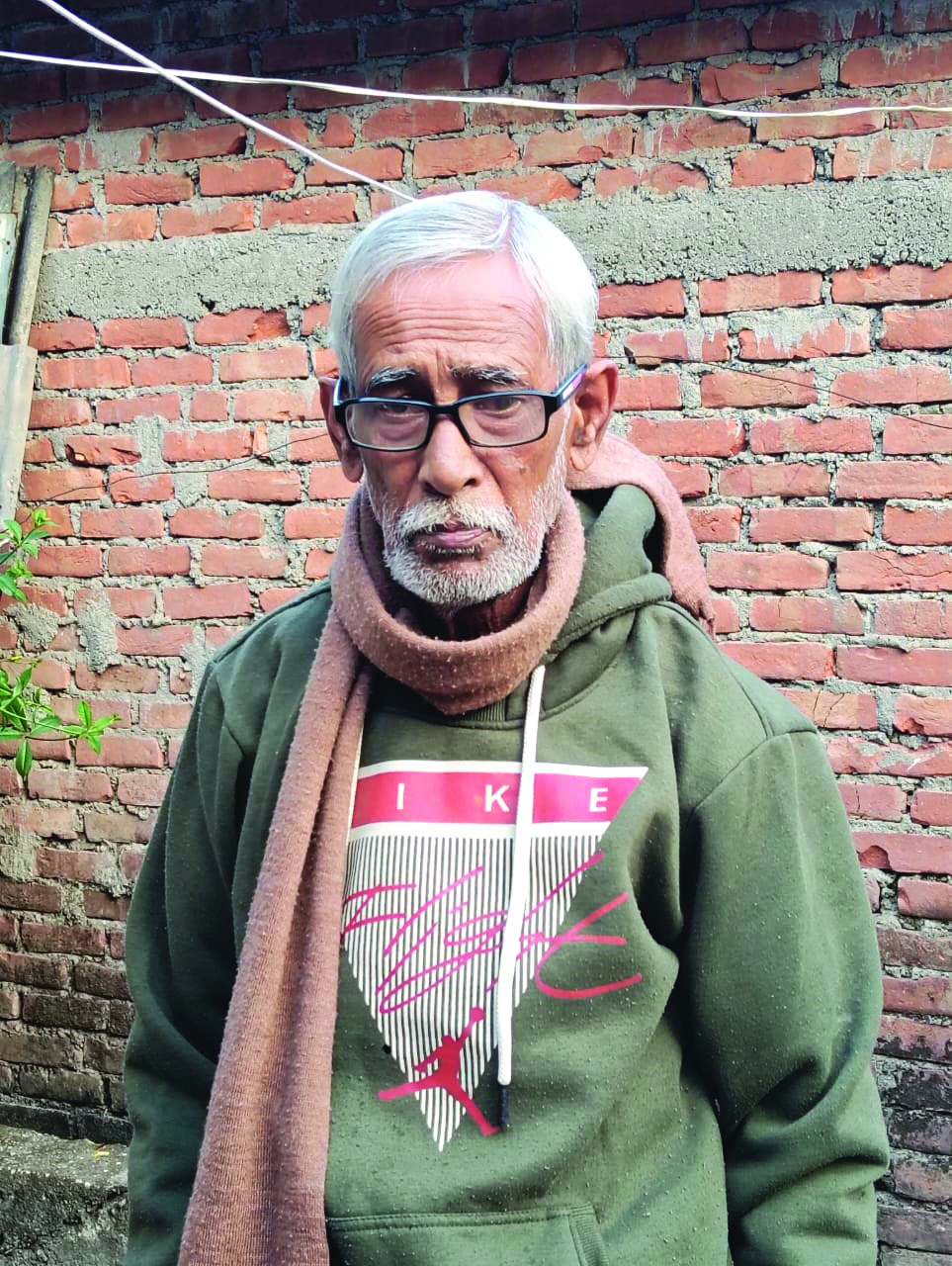

In an exclusive interview to Millennium Post, Chowdhury stated: “The independence we fought for came at a great cost. Today, many Bangladeshis carry the legacy of those who opposed liberation. Their children have grown up with the same sentiments and will never align with India.” Sitting in his dilapidated house in Chalsa, Jalpaiguri, the man often referred to as the “James Bond of Bengal” recalled his dangerous missions and the eventual creation of Bangladesh. Chowdhury fails to fathom out the current anti-India sentiment in Bangladesh and also against the minority religious communities who had also actively participated and made the supreme sacrifice for the liberation of the country.

Born in Kushtia of Faridpur, Bangladesh, Chowdhury was an important member of the Mukti Bahini. Armed with his camera and a fierce resolve, he documented Pakistani military movements, clandestine meetings and operations. Operating undercover, he mastered Urdu to blend in and worked as a photojournalist for Ittefaq newspaper to maintain his cover. He recalls the day Pakistan surrendered on December 16, 1971, as one of profound personal significance. “The moment I heard of their surrender, I removed the sacred thread from the amulet and resumed my identity. That day will remain etched in my memory forever.”

After the assassination of Bangladesh’s founding leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1975, Chowdhury fled to India and settled in Chalsa with his family. Despite the personal risks he took during the war, he feels disheartened by the persecution of Hindus in Bangladesh and the diminishing recognition of freedom fighters’ sacrifices. “We did not envision an independent Bangladesh like this,” he says. “The atrocities against Hindus and the anti-India narrative make me question if our efforts were in vain.”

Today, Somnath Chowdhury lives a quiet life with his wife, son, daughter-in-law and grandson in Chalsa. Chowdhury also recollects the critical role of training camps run by the Indian Army in the Dooars region, particularly at the Murti Tea Garden in Meteli, where Mukti Bahini members were trained during the Bangladesh Liberation War.

He believes a memorial should be erected in Meteli to commemorate the region’s contribution to Bangladesh’s Independence and the sacrifices of its freedom fighters.